|

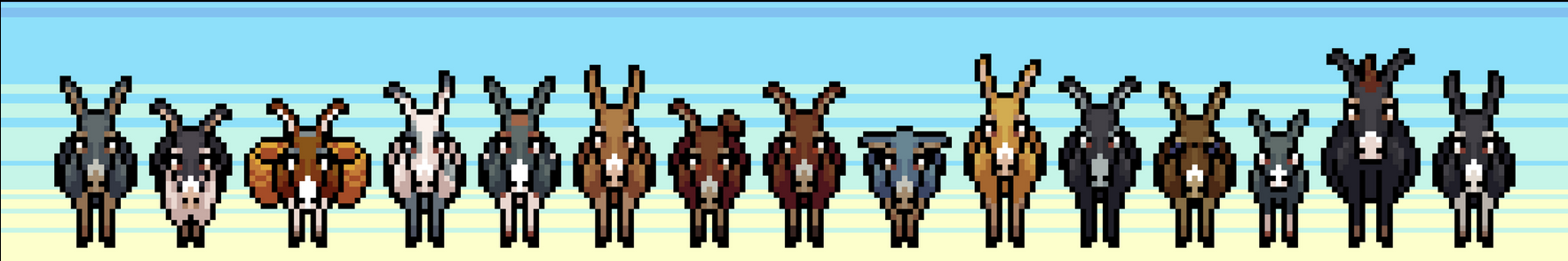

with writing from Jenn Stephenson, Mariah (Mo) Horner, Derek Manderson, Charlotte Dorey, Benjamin Ma, Bethany Schaufler-Biback, and Jacob Dey Created by Patrick Blenkarn and Milton Lim with dramaturg and touring producer Laurel Green, sound designer and composer David Mesiha, digital artists Clarissa Picolo, William Roth, Ariadne Sage, and Samuel Reinhart, [1] asses.masses can be simply (but perhaps reductively) described as an eight-hour video-game theatre experience. The show was presented at the Festival of Live Digital Art (FOLDA) in Kingston on 8 June. The plot of the play-game follows a herd of asses from Fannyside Farm who contemplate the value of their labour in relation to humans and to machines. Over the course of ten episodes, eight-hours and an uncountable number of ass jokes, we take turns playing as the donkey avatars (being the asses) and shouting out (usually helpful) advice (being the masses). Given that a core dramaturgy of the show is what its creators call the “politics of the basement,” where we take turns either playing the video game or sitting on the (metaphorical) couch heckling and encouraging the current player, we thought that a similar serial approach to writing about the show seemed appropriate. (“ASS POWER!”) Several people who participated in the Kingston show have generously shared their thoughts here. We’ve selected some excerpts from their writing. If you want to read more, follow the links below each section. Mariah writes, “Duration allows for participants to settle into this community, to take off their socks and share snacks. Duration allows for time to negotiate turn taking and role playing without too much pressure. Duration gave me the time to consider picking up the controller and then ultimately decide against it. Duration gave the hecklers the space and validation that sometimes shouting out ideas is a type of team playing. Duration also allowed for the sort of chaotic unraveling of our theatrical tendencies…. As shown in asses.masses, duration has the potential to both generate and destroy. We could grow as a herd while we shed our theatrical tendencies around sitting still and being quiet. We could create community and destroy the passivity of the spectator.”

Jenn writes, “I was curious as to how often the controller would switch hands. This is a key nexus point of social negotiation by the audience-herd. Who will lead and for how long?… I realized here that precedent is powerful. The first person played the whole first episode and after that each subsequent person also completed the whole episode. There were a few attempts to hand off the controller mid-episode, but the offer seemed feeble and any potential taker didn’t move fast enough to make their desires to play known before the current player resumed. There is also potential for more frequent changes of possession of the controller. For example, taking turns playing the mini-games or allowing a more “expert” or agile player to navigate a difficult sequence. Of course, this question of who leads, and the changes of leadership is central to the plot of the show. Obviously, there are asses and we are the masses. Different asses assume leadership of the herd at different points in the narrative.”

Derek writes, “I’m someone who loves to participate. I also love games. I think I’m pretty good at them too. But I found myself quite anxious about stepping up to claim the controller and take the lead…. I had several supporters who encouraged me to stand up each time there was an opportunity for the player to switch. Yet I remained glued to my seat, tied down by an invisible force of insecurity. So, why did I feel this way? The social pressure was a big factor. In the latter half of the performance, it felt to me as though there was significantly less patience in the room. We had built a rapport as a group which included a fair amount of shouting. We had grown familiar enough with the game for audience members to confidently become backseat gamers. At this point, I’m not sure people wanted to see a fellow audience member play the game, but rather, for them to serve as a physical conduit for progressing the story. There is a distinct pressure when individual performance is responsible for group progression. What if I couldn’t do something right? What if I made a bad decision?”

Charlotte writes, “Sending an audience member up to that podium is a sign of trust, and that faith creates a sense of responsibility to the “herd” that is extremely affective for the audience player. To step up to the front and agree to make decisions on behalf of the group is a brave thing. Still folks seemed to get bolder over the course of the show’s duration and more went up as the show neared its conclusion. It doesn’t take that long to build a sense of community, and as a collective we quite quickly set a tone where folks felt comfortable shouting out suggestions and tips to the player at the front. They may have stepped out of the audience physically but they are still one of our own. Even though the controller is in their hands, we are working together.”

Bethany writes, “Without the presence of a performance rep for the production outside of the game itself, audience members were required to look to one another to learn the norms and expectations of our temporal collective. This proved to be fairly successful as demonstrated by the repetition of events, how the game would start after intermission, how much time an audience member would spend at the controller, how mini games were approached became predictable. We established our own ‘etiquette’ that was abided by throughout the entire 7.5 hours. I think this is largely attributable to the value of the positive affects within the audience collective. Working towards a common goal, achieving a mini game and moving forward felt good and was cause for celebration. Through the various chants that arose out of audience inside jokes created as the game progressed, I became tied to the positive affects experienced through my body as a result. I didn’t want to act out of turn or against our communally decided government as not to disturb the positive contagion within the audience, holding onto an affective glue which supported our government. I would assume that this was felt by other audience members as well.”

Benjamin writes, “The physical configuration of the room allows a player to step forward from the herd, as Thespis stepped out of the chorus, to assume the position of the ass who will lead our journey. Once they assume the position, they are voluntarily stepping into a position of alienation as their backs are now to the audience and the top and side lights create a barrier between them and us. . . . By the end of the night, I felt as though something had shifted within the audience. What was once a group of strangers remains a group of strangers, yet there will always be a sense of familiarity to them; a familiarity dictated by a game, and established by the bravery it takes to separate from the herd and speak on our behalf.”

Jacob writes, “Thought #5: I'm a theatre kid, I do not shy away from attention. I do not want to grab the controller. I do not want to be subject to 40 backseat drivers. I press the x button to end the intermission and sit back down. Someone else can do the work.” READ MORE.

Stay tuned for where asses.masses will be next by checking out their website and following them on socials. [1] Although not featured in the version of asses.masses we saw at the Festival of Live Digital Art (FOLDA) in Kingston, the show also features a Spanish translation done by Marcos Krivocapich.

0 Comments

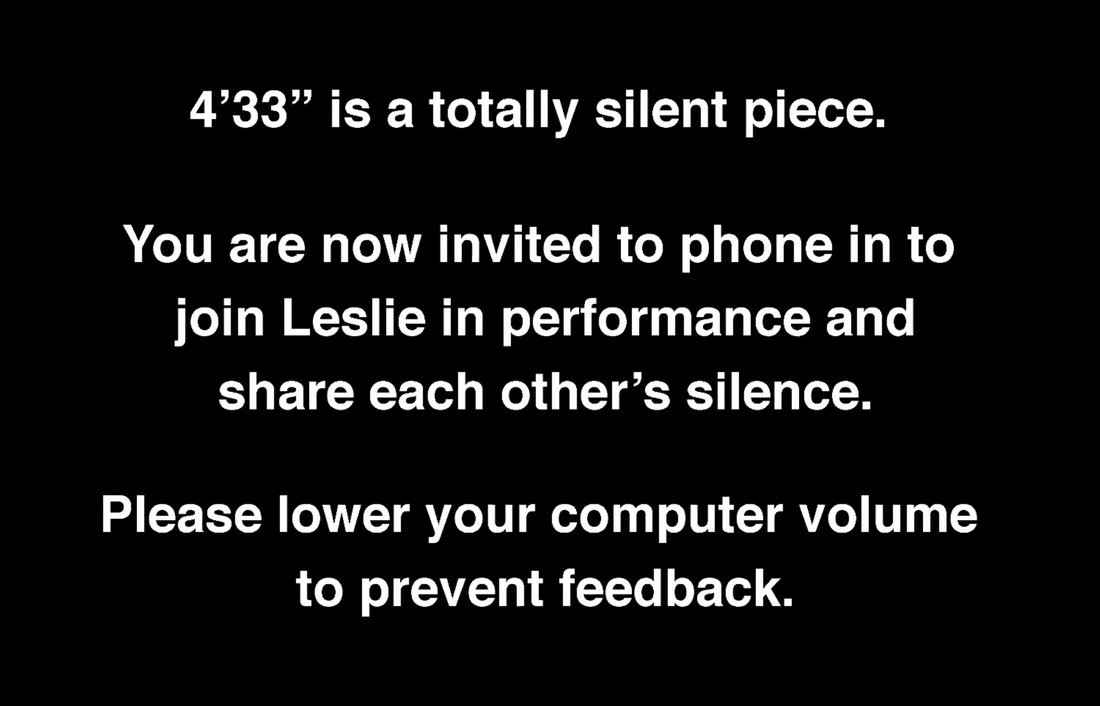

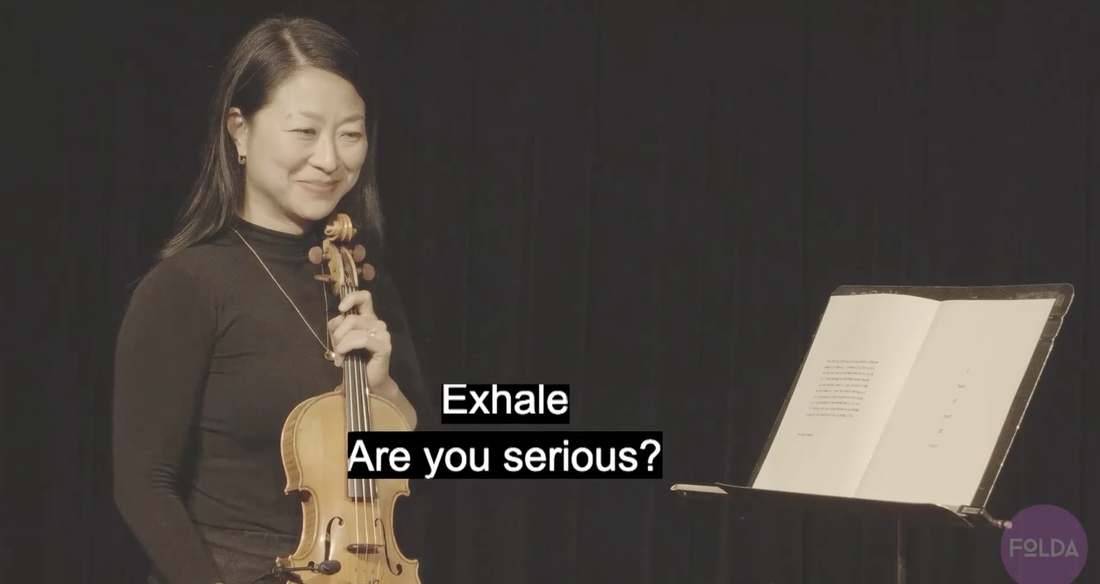

Mariah (Mo) Horner with Leslie Ting Mo: So I want to talk about your shows Speculation and What Brings You In specifically through the lens of participation. I thought we would maybe start with Speculation? I'm wondering if you could walk me through both what happened in the show and maybe explain a bit of your artistic process of arriving at the thought that participation was key to this work. Leslie: So the version that you saw of Speculation was the pandemic version which we staged online at FOLDA in 2021. Speculation was a theatrical concert with an immersive visual design based on the experience of vision loss. The show featured a monologue interweaved with live performances of Beethoven and John Cage to tell the story of my mother slowly losing her vision. In the online performance, everything up to the final participatory moment was pre-recorded and edited with experimental film. After the recorded concert we would go live in this final moment to collectively perform John Cage’s 4’33, a work entirely of “silence”. To participate, we encouraged audience members to phone into a phone number where I could hear everyone on the call and everyone could hear me and everyone else on the call. That connected conference call was then streamed online, which inevitably included feedback looping from all of the simultaneous phone-ins. There was a lot of balancing. We would ask people in the instructions to turn down their computer volume if they were also going to phone in so we could avoid the feedback that was gonna happen, but it was inevitable. Mo: I remember watching the show with a group of people. So we had to mute the laptop and put the phone on speaker. The risk for ambience feedback is high! Leslie: All you can do is sort of offer the instructions and then people are gonna do what they want, feedback was fine. That participatory element was very important to me when I was asked to pivot the show to online presentation. Speculation as it was was a theatrical concert that wasn't going to be captured well on camera, because of the way the lighting and video was designed. It was important to me that the online version still had this feeling of experiencing something together, with other people. Cage’s 4’33 is a heightened listening piece. All of Speculation is about listening, but when participants land in 4’33, I really wanted them to feel and hear each other’s lives. Listening is interactive. 4’33 is formalizing that idea of co-creating through listening. If life happens, life happens. If someone turns their livestream too loud, it’s fine. I think that while we tried hard to create the “silent” experience, because 4’33 is a silent piece, the piece is more about unintended sound and listening for that. There is an intent to be silent but you’re also really being open to sound at the same time. Mo: Oh, I love this! Leslie: I don't know if you remember but in our FOLDA performance, early in the phone call section someone said “Are you serious?” and it just started looping over and over again. We were laughing because that is such a perfect moment! I'm sure someone was caught off guard about listening and being heard. We were performing together in some ways, even more so than in the version where we would have all been together in a room pre-pandemic, because people made the choice to pick up the phone and join me. Mo: I want to talk about listening as a participatory activity because I know that you're also a musician! When we first started writing the book, we got into a major question around how typical traditional bourgeois sit-in-the-dark kind of theatre is also participatory, right? Interpreting, listening, watching, and considering are also participatory actions. Can you tell me more about why you think listening is participatory? Leslie: This was one of the biggest sort of realizations I had to make coming from the concert music world to the theatre world. In making Speculation, there was almost an immediate awareness that theatre audiences expected more. You can't just sit there and play the violin and think that's enough in theatre, most audiences need more lighting design, more characters, more narrative. Theatre audiences are leaning farther forward when they attend a show, they're waiting for you to take them somewhere. Music audiences are really used to being internal and they're not expecting the same kind of journey. The invitation for me in making Speculation was not necessarily to give you a narrative journey, but to invite theatre people to go inside and actively be with themselves. It’s like my experience with contemporary dance. Sometimes I feel like contemporary dance is hard for me to grapple with. I don't always know what is happening. But I would try to sort of understand it. I would try to internally meet it partway Mo: That makes sense to me! Music audiences are showing up to these experiences expecting to carry the interpretive labor, the participatory labour of “meeting it partway,” whereas traditional theatre audiences are sometimes less practiced in the labour of interpretation. This leads us to talking about your other show, What Brings You In. That show is also a softly participatory experimental music performance that explores the ways in which we engage with the therapeutic process and therapy is definitely participatory. Leslie: What Brings You In seeks an internal engagement and leaves space for multiple experiences . I know it’s alienating when you feel like you don’t “get it.” Learning the language of contemporary dance or new music can be alienating at first! I want to give my audience permission to just be with the sounds and I feel like sound is one of those things when you put it together with anything visual it competes, and so it’s the person sitting in the chair that decides where their attention goes. That’s also participatory. Mo: Let’s talk about one of your other major interests in making participatory work, accessibility. When you're staging something like What Brings You In, what are the implications of staging elements of the therapeutic process? What kind of things do you keep in mind as a creator? Leslie: In making What Brings You In, I realized that accessibility is complex. You’ve obviously got these government standards for things like public retail store websites around accessibility but the reality is, accessibility needs are nuanced and sometimes conflict with one another. In What Brings You In, I decided to instead focus on one set of access needs and go deep rather than do everything we can to offer shallow access needs across the board. As an audio-heavy piece, it was well suited for audience members with blindness and low vision. As you know, connection through interactivity is important to me so during What Brings You In, participants are welcome to move a cursor on their devices, like a calming doodle that was then projected on a screen. I worked with Marie Flanagan and Jess Watkin to balance care with the risk of overburdening people with too much explanation in the invitation. It took a lot of testing. We avoided text because it’s often inaccessible to folks without vision and we wanted sighted people to feel comfortable looking away from the screen and softening their vision to go more internal. Mo: Right! I remember when I saw What Brings You In, the staging decision to have you on the opposite side of the room to the screen was also a reminder that neither spot needed to hold my gaze for too long. I quickly realized that you were asking me to lie down and relax, receiving the information through my ears. This point that you're getting at around gaps and holes and giving the audience space, is connected to the earlier conversation that we had about experimental music. Offering the freedom to interpret and participate however is almost an access need? I feel like usually we think, at least in the context of participatory theatre, that access is mainly adding on top of the performance. Access is a supplemented thing. It's very interesting to hear you think about access as openness and emptiness, gaps and holes. Leslie: Yeah! Access as an additive thing is totally what seems to happen in theatre, and we tend to add it at the end. But it's more chaotic than building something with a specific set of access needs at the forefront. Mo: I once heard Calgary-based artist Jan Derbyshire say that in terms of access needs, “one size fits one.” Leslie: Exactly! This was a huge challenge for What Brings You In. In workshops, we kept getting recommended to add closed captioning but if you put words on a screen, that's all you're going to look at. If you're a sighted person or you have even partial sight, you're going to be drawn to that text. Or, for blind folks, screen readers will go off and distract you, we had to be ok with that. My interest with What Brings You In is to invite participants into this world of new music around self discovery and self understanding, through listening with others. The interactivity is important because I wanted the connective live experience still felt. There are still many gaps in the implementation and we want to give people the feeling of interacting and co-creating with plenty of space. Mo: The cursor reminded me of a classic fidget toy. I could see how it would help in listening. Leslie: I don't think we practice listening in general as a society. We're super good at watching and looking at details and having thoughts and feelings about what we see , but we're not as good with sound. Elinor Svoboda, one of the filmmakers for the pandemic version of Speculation who specializes and teaches sound in film, talked to me once about sound accessing the lizard part of the brain. I think hearing people are just not as practiced at interpreting sound like we do vision t.

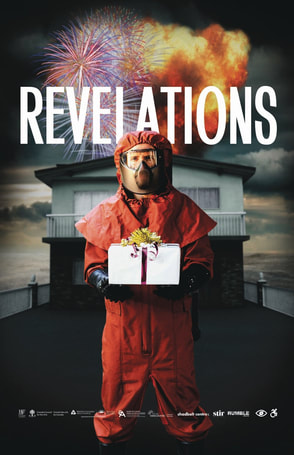

Mo: Tanya Marquardt’s Some Must Watch While Some Must Sleep uses the distance of texting and the closeness of audio to access some kind of deep listening. The show is a texting conversation that takes place every night for a few weeks. During the show, this series of meditations on sleep and dreaming and healing from trauma pepper the texting conversation. You’re texting, you're talking about dreaming, and then all of a sudden you get a link to an audio meditation and your conversation partner says they’ll talk to you tomorrow. It was pretty intense, really intimate! The distance from the artist, the fact that I didn't see the artist and only texted them was an interesting tension with the intimacy of the sleep meditations. In the case of What Brings You In, the invitation not to watch and instead to relax offered distance. The therapeutic self reflection was intense but the softness of the gaze soothed me. Sometimes a kind of distance is very freeing as an audience member. Leslie: Yeah—fascinating. Mo: Gosh, this has been really great. I think really specifically, your perspective as an experimental musician on listening as a participatory act is really rich. I'm so interested in your thoughts around gaps and holes as an access offering. Leaving ample room to interpret can be an invitation to participation. Openness is also an invitation to participate. #ThrowBackThursday. In this post, I’m reminiscing on the show Revelations created by Toronto-based theatre creators Anahita Dehbonehie, Griffin McInnes and Aidan Morishita-Miki which I saw just over two years ago at the Kick and Push Festival in Kingston, Ontario [1]. I saw this show in the summer of 2020. At that point, we had stopped wiping down all our groceries and fully isolating from the public, but we were still unsure of whether we’d be heading back to campus in the fall. The only people I talked to unmasked were my roomates - everyone else I hung out with exclusively digitally. Enter Revelations: a game wrapped in a show about the apocalypse, but not the one that we were living - the potential future nuclear apocolypse. The day before the show, a man in a hazmat suit knocked at my door. I knew that he was coming of course, he was dropping off some of the materials my group would need for the game the following day. In this package was a walkie talkie and some papers with game components clues. He placed the package in front of my door and then stepped back across the street. He asked me a couple questions via his own walkie talkie - if the power went out right now, what would I have for dinner? Did I have people I could go to? I could tell he wanted me to start thinking about what I would do if a major apocalypse was upon us. He thanked me for our conversation, reminded me of the instructions I was to follow the next evening and then left, hazmat suit swishing as he walked away. During our scheduled show time, my bubbled roommates and I gathered at a table in our backyard. We spread out all the things in our box on the table. In addition to the walkie talkie, there was also a series of clues that would eventually lead us to the meet up location for the second part of the show along with some papers that explained the rules and other game mechanics. By talking to other groups in their own household bubbles around Kingston via walkie-talkie, we had to decide what mode of transport each of us were going to take to escape nuclear fallout: car, boat, or on foot. Due to numbers, the best decision for the group would be the boat. The more people that chose the boat, the better odds of survival each of the boat-groups would have. For this show, those odds of survival were represented by a roll of the dice and the more people that picked boat meant the more dice those people had at the end of the night in their attempt to survive. It was an exercise in collective care or individual risk-taking. The sticky part comes with the car; if one group picked the car, that group had much higher odds of survival (i.e. many more dice). If more than one group selected the car though, they would have to play a game of rock paper scissors to determine who would get it. The losing team would have to walk and therefore have next to no chance of survival (you rolled one die). There were also some other factors to consider. In our boxes were also some pieces that were specific to each group - for example, one group had a piece of paper that let them know that if there was conflict between their groups that resulted in more than one group choosing the car, they would be granted an additional die. Another group was granted an additional die if all five groups chose the boat. Communication by walkie talkie was perfect for this show - narratively, it is a low-tech solution that would work when the rest of the technological ecosystem collapsed. They are also, for many of us, a relic from a time when we were younger. I know I associate walkie talkies with running around the woods with my cousins during the summertime. It also meant we had to choose to talk, as opposed to phone calls or video calls- those are open channel of communication where turning away and talking to your group is the active choice, instead of pressing the button to share with the rest of the groups. When you are at an in person participatory or game-based show, you have to turn away and whisper to not be overheard, whereas the walk talkie meat that secret conversations within your group is the default. They also add to the distancing effect for this section of the show. My group spent most of the walk to the second part of the show talking about what we thought about the other groups and what the gathering we were heading to might look like. At that point the only information we had was the location, Confederation Park in downtown Kingston, a perfect setting for this section of the show. In actuality, you could walk, drive, or take a boat to and from it. Once my group arrived at Confederation Park, we did a couple laps before we stumbled upon what looked like a party being set up. There was a table with what appeared to be a DJ, lots of lights, some balloons as markers for where each household should stand for social distancing purposes and a large table with cupcakes, chocolate and vanilla. We were told that the cupcakes were the reward for the ‘survivors’ (in the end that just meant that the winners got first pick; we were all invited to take one once the show had concluded). Also arriving at the meeting place was a group of households that had done part one of the show with each other the day before. As other folks started to arrive, guilt started to creep into my heart. This was a game, and the real-life consequences were nil, but seeing these people instead of just hearing their voices made them so much more real. In his book Post Dramatic Theatre, Lehmann says, “Theatre takes place as practice that is at once signifying and entirely real. All theatrical signs are at the same time physically real things.” [2]. As audience members, we become scenography, aesthetic parts of the show, as well as practical ones- within the diegesis of this play, our lives are on the line, and our betrayal endangers the lives of others. On one level, I know that there is no actual risk of bodily harm in Revelations, especially not from a nuclear apocalypse. And yet, I still feel the ‘realness’ of this show affecting me. All the physical stress markers showed up- I felt my pulse quicken with each new group that meant we were getting closer to beginning the rolling of the dice, and my palms were starting to sweat. My fellow audience-participants were not actors, they were exactly like me. Similarly, we were playing a game that simulated the end of the world while living right in the middle of a global health crisis. Once again we see the world inside and outside of the fiction of the play begin to collide. It was much easier to know the ‘right’ thing to do in the game than it was in our real lives and real international emergency. Eventually, the same man I had talked to the previous day strolled to ‘centre stage’ (i.e. in front of the DJ table) and announced into his microphone that we were going to begin the next phase of the performance. After yesterday’s cohort had all gone, our show’s groups were invited, one representative per group at a time, to roll their dice and determine their fate. My roommates, chickens that they are, nominated me immediately. When it was our turn to reveal that we had chosen to take the car, no one looked surprised- we found out afterwards that our walkie talkie had some technical difficulties and they could all hear our scheming when we thought they couldn’t. C’est la vie! Unsurprisingly, we ended up losing the rock paper scissors battle for the car against the family standing next to us and had to walk away from the apocalypse. Eventually, it came time for me to roll our die. I thought about blowing on it for luck but decided that wasn’t the best idea during a global health crisis, and so I picked them up, put all the positive energy into it that I could muster and rolled. I can’t remember exactly what I ended up getting, but I do remember that it was not enough: we did not survive the nuclear apocalypse.

At its core this show was asking us what we valued more, the individual or the collective? Participation is, by definition, not something you can do alone. And yet when we look at the inspiration for this show we see so much individualism. Doomsday preppers create bunkers for themselves and their loved ones, preparing for the day when a natural disaster, economic collapse, or nuclear war means that it’s everyone for themselves. In it’s sim, Revelations asks us to confront our own approach to the end of the world; it offers us valuable lessors in collective care that can be applied easily to our real world. My relationship to my fellow participants changes over the course of this show, the gap between us closing as we come together in a shared space. The novelty of congregating like this was only magnified by the months of social distancing we had adhered to at this point. In her book Utopia in Performance, Jill Dolan says “Audiences form temporary communities, sites of public discourse that, along with the intense experiences of utopian performatives, can model new investments in and interactions with variously constituted public spheres.” In this case, we are actually engaging with almost the opposite of what she calls utopian performatives, which are “small but profound moments which performance calls the attention of the audience in a way that lifts everyone slightly above the present, into a hopeful feeling of what the world might be like if every moment of our lives were as emotionally voluminous, generous, aesthetically striking, and intersubjectively intense”. Revelations askes us to perform dystopia, as we rehearse for the apocalypse. Still, Dolan’s ideas on the choice to gather in a public space prove relevant, especially at the height of pandemic anxiety. We were performing one kind of apocalypse in worldB as we tried to navigate a different one in worldA. Works Cited

[1] Dehbonehie, Anhita, McInnes, Griffen, and Morishita-Miki Aidan. Revelations. Kick and Push Festival, 31 August 2020, Kingston, Ontario. [2] Lehmann, Hans. Postdramatic Theatre. Routledge, 2006. [3] Dolan, Jill. Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater. University of Michigan Press, 2005. The goal of Aurélie Pedron’s 72-hour, durational, dance piece Invisible? “Make the intelligence of the collective visible.” The title suggests that if our collective intelligence is generally invisible, three days with dancers and a dog (I’ll explain later) in a dedicated collaborative space can open our eyes to what we are truly capable of (or what we’re already doing), together. While the piece is participatory, asking for participants to feed into the collaborative action, Invisible’s show prompt reminds us that we are more than the sum of our actions and that what we are looking for is always already present behind the curtain. Before I continue, it’s important to offer a character description, specifying the “we” that I write about in this blog. In May 2022, my partner Cameron (a brave but slightly suspicious participator) and I made our way down the 401 to Montreal’s venerable OFFTA to see Invisible, a piece by Aurélie Pedron (of Lilith & Cie) co-produced Danse-Cité, LAVI – Laboratoire Arts Vivants et Interdisciplinarité, Département de danse de l’UQAM. [1] We arrive at Invisible around 2pm on Saturday, around hour 36 of their durational experience. We are met by a guide who invites us to play a tabletop game to learn the rules of Invisible. He shows us a game board that mirrors the geography of the performance space that we are about to enter. From a deck of special instructional cards, he lays out a series of cards that speak to the values of the show and suggestions for our participation. The cards say things like “silence is a possibility” and “do nothing, receive” or “now might be a good time to play your music.” The cards are participatory offers from the artists. Cameron and I talk to him. He shows us the vastness of space where we are welcome. He points out eight aux cables along the perimeter connected to speakers, a gramophone, and a tape player. He delineates the small section of the room that is only for the dancers. After he tells us the goal of the game, making “the collective intelligence visible,” we are given a new set of six cards and told to choose two that speak to how we are feeling right now. Where the first set of cards are offers, these cards are feelings or states of being. I chose “I’m in a good mood” and “I’m feeling a bit shy.” I return them to the game master and he gives me two cards in return, “let it be communicative” and “listening is an action.” After this exercise on invitation, we are told to exchange our shoes for our own complete deck of offer cards full of more participatory prompts and suggestions. If we’re feeling stuck with what to offer once we enter the dance constellation, we can pick a card and let it guide us. The cards offer actions like “go whisper/say/sing something to a dancer” or “go lay down in the center of the space” or “find a moment to go look out the window.” Episode 1: Saturday May 28 @ 2pm Shoeless, I open the door to the performance space and it feels like I’m entering a portal to another dimension. It’s quiet, aside from the sounds of dancers in socks gliding on the floor in the center of the space. Four or five dancers move in silence while audience members are cozied up on chairs around the perimeter of space. Cameron and I immediately find a safe space in the corner to pause and take it all in. I ask him if he wants to explore but his feet are glued to the floor, his seat to the chair. I explore the perimeter alone while the dancers continue to glide in near silence. Directly opposite Cameron, I find a hammock with a sleeping person, a telephone, a lighting board with a cue sheet, and a cork board with a bunch of family pictures. I push the button on the lighting board for cue 61 “cyan” and then (like a bad lighting designer) immediately change my mind in favour of cue 63’s “red red red”. Then, I see Rachel’s notebook. I remember a card from the deck that said I could write something in a dancer’s journal and I gingerly open the green book. Many of the entries are in French but some of them are in English. She writes, “I’m exhausted but my yellow pants are bringing me joy.” I scan the room for yellow pants. I find her (and her pants) and I laugh to myself. I know you but you don’t know me. I talk to her in my head. I keep reading. She writes of the kind of elation and joy she feels in this sustained practice. She recognizes people by name and clothing. I write her a note and tell her that I really want to play but the room feels too quiet. Because I find dance profound, I’m feeling pressure to contribute something profound in comparison. I put the book back where I found it. I look up and watch the lights change from teal blue to deep red and return to Cameron satisfied with my first few interventions. I tell Cameron about the treasures I found in the corner. He nods, overwhelmed but open still. He’s concentrated on our first guide’s reminder: observation is participation. Suddenly, realness upsurges. A baby. The dancers and the assembled audience watch with baited breath as the baby crawls into the center of the room, softly making her way through the improvising dancers. The energy of this interruption is electric. The music stops and the baby clocks that they are suddenly the centre of the action. They raise their hands. The dancers do the same. The baby gurgles. The audience laughs. Episode 2: Saturday May 28 @ 9PM We return, prepared and excited. Between 2-9PM, Invisible’s dancers continued their sustained exploration of collective joy and play in the theatre and I walked about 15,000 steps through Montreal. I talked with Cameron about what songs we’ll play when we have the courage to take over the aux cord. My feet are sore but I’m sure the dancer’s feet are more sore. As time passed for the dancers, it did for us as well. When we arrive tonight, the energy is very different. A bit more playful and sexy. A group of six dancers are running and jumping about the space to something that sounds like Joe Cocker or 70s Beatles. Although no longerwearing her yellow pants, Rachel is feeling joyful. She’s laughing. The dancers seem to be balancing between exertion and pleasure in every passing moment. Time passes. Silvia (Cameron and I look online to match photos to faces to learn their names) is wearing purple splash pants dancing in a Motown duet with Charlie. They are having fun. Suddenly, the dog approaches Cameron and I for a welcome sniff then returns to her comfy bed. Then, a bright purple light comes on in the corner with the hammock and Aurelie, the creator, answers the phone. She greets the caller and then passes a set of bluetooth headphones to Charlie who is dancing in the middle of the room. He talks to the caller in English while he dances with the group. “The body is finite and I’m feeling that,” he says, “but the spirit is infinite and I’m also feeling that.” Episode 3: Saturday May 29 @ 2AM We walk to the theatre a different way tonight, weaving through the alleyways, eavesdropping on various backyard parties and inhaling secondhand smoke. We, like the dancers, are equal parts exhausted and energized. We get to the building and from our vantage point outside, Cameron points to a third story window. We see the disco ball inside the theatre spinning in soft purple light. The world turns and so does the disco ball. The vibe is very different in the middle of the night. The dog is sleeping deeply on a pillow. Three of the dancers are vibrating in silence in the middle of the space. The energy in the room feels manic under exhaustion. It looks a bit…scary? Uncomfortable? Hyperfocused? It feels like a too-late end to the party. The vibrating continues for about 10 minutes until Aurelie walks over to a gong and rings it and all three dancers stop vibrating immediately. Aurelie plugs her phone into one of the aux cords and sharply changes the feel of the room with a new song. As the dancers bounce around to Lee Perry, under thehanging speaker that looks like a UFO, there is a reclining couple, making out. I think about consent and care and wonder if the limits of this kind of free sustained play are more likely to be pushed in the middle of the night. The kissing couple stops and one of them puts a rave song on the speaker. The heavy EDM beat reverberates in the room. The dancers come over to the couple and they all dance together. I lie down on the carpet and I feel like I could fall asleep. I wonder what would happen if I did. Episode 4: Sunday May 30 @ 3PM We fell asleep at 4am the night before, making a playlist of songs we could bring to the dancers. Cameron wondered what would happen if he played something hardcore. Would the dancers enjoy dancing to our songs? Would heavy metal scare the dog? For the first time, we can hear the music from outside the room when we arrive. When we enter this time, there are nearly 30 audience members in the space. This is more people than we’ve seen so far. We sit in a corner on a wooden bench with an aux cord and settle in. As we get cozy, I see a familiar pair of yellow pants approach me. Rachel sits beside Cameron and says, “Have you tried playing music yet? It’s fun, you’ll like it.” I laugh, feeling an intense familiarity with this person and wondering if she recognizes us. She’s encouraging us softly. “This speaker is pretty quiet, so it’s like you’re the only people who will hear it.” She walks away and Cameron and I look at each other with determination. I play my song. The bench vibrates below us and we realize the speaker is under us, shaking our seat and reverberating the bass into the room. The people close to us start tapping their toes and I feel…satisfied. I feel like a good party guest. I honoured the aux cord. I flash Rachel a thumbs up. Rachel comes back again and offers us each a piece of chocolate. It’s like a reward. On the other side of the room, there is a woman who is dominating the aux cord, playing a few songs back to back. To switch up the vibe, Sylvia plugs her own phone in and plays Quebecois rap with a heavy bass. She turns up the volume. I follow this thread and play a song that reminds me of growing up with a group of Caribbean girlfriends in Ajax. Sylvia smiles at me. We decide it’s time to make the trek back home to Kingston. I approach Aurelie and my favourite dancer Caroline to thank them and we leave the theatre at hour 71. The space for a heterogenous participatory experience redeems Cameron’s faith in the power of theatre’s collective gathering. On our drive home to Kingston, I call the theatre phone and leave a message to thank them all for their sustained discovery. They return my call almost immediately. I answer my cell, surprised to hear someone specific. “Hi Mo? It’s Rachel, I got your message.” I laugh, “Rachel, oh my god, it’s you!” She says “I know you, I got your note.” We talk about how she’s feeling, and she tells me she feels like a cloud. I give her my love for the last thirty minutes of the show and we continue our drive back home. This show is worth a lengthy description of its parts that I’ve provided here because according to how I understand the show’s purpose, these parts are the gaps in the fabric that reveal the collective intelligence. This is how we peek behind the curtain of the everyday. The copycat baby dancing. The soft negotiation around hogging the aux cable. The chocolate in exchange for a song. Following the yellow pants and falling in love with the dancer wearing them. Through its gentle touch around seeking participation (however small or mighty) Invisible puts a lot of faith in performance’s capacity for generating emergence. Much like the folks in my citational universe, Invisible is actively creating (or recreating? or revealing?) a new world that emphasizes observation, interaction, negotiation and collaboration. A new world that is already there if we look hard enough. Invisible insists that the collective intelligence is already in the room, we just need to reveal it by being patient, being here and now together and negotiating our actions in a collective. Using “time as a compositional tool” [2] in this way can present an antidote to the notion that time is money, time is commodity. In Invisible and other durational worlds, “time-based dramaturgies in the work directly aim to foreground the complex subjective experience of time that often belies accelerated contemporary living.” [3] In her work Dancing on the Turtle’s Back, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson emphasizes that taking the time for simple presencing can act as a key to accessing (re)created realities, drawing on Nishnaabeg creation stories to insist that “creation requires presence, innovation, and emergence.” [4] Simpson says, “[Performance art] because it is based on process, contradiction, action, and connection, is closer to Indigenous ideas of art and resistance.” [5] Simpson furthers these ideas of presencing and the (re)emerging new world in her remarkable new collaborative monograph with Robyn Maynard, Rehearsals for Living. A series of letters between Simpson, an Indigenous artist-scholar and Maynard, a Black feminist and writer of Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present, Rehearsals for Living, like Invisible, insists that the world that we desire, specifically the new world that is fueled by liberatory fire, is happening constantly in dynamic rehearsal. The collective intelligence is already in the room. In the foreword, Ruth Wilson Gilmore says the book is oriented towards the “historical geography of the future” that “the purpose isn’t to document that a specific thing happened, but rather to offer thickly analytical, detailed, descriptions of many different ways people arrive at arranging themselves into a social force.” [6] In Invisible, there is no plot or characters besides the folks inhabiting the room, existing and exhausted, in the here and now. The space provides the container for us to arrive and explore these ways of arrangement so we can both reveal and imagine the future that is already here. Works Cited

[1] https://offta.com/en/evenement2022/invisible/ [2] Deborah Pollard. “Entanglements with Time: Staging Duration and Repetition in the Theatre,” Australasian Drama Studies, no. 76, 2020, p330. [3] Deborah Pollard. “Entanglements with Time…” p331. [4] Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Dancing on the Turtle’s Back, Arbeiter Ring Publishing, 2013, p93. [5] Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Dancing on the Turtle’s Back, p96. [6] Ruth Wilson Gilmore. Forward to Rehearsals for Living, Knopf Canada, 2022, p2. A personalized sermon on a cassette tape track, a meringue as communion, and a blessing from a Beanie Baby named ‘Goochy’: these are all things I received as an audience-participant at Holy Moly, created and performed by Jarin Schexnider [1]. Holy Moly delves deep into Schexnider’s middle-class upbringing in Louisiana in the 1980s. This formative decade provides the context for her exploration into her relationship with what is ‘holy’ and sacred. When I entered the theatre, I was greeted by a full altar of items that were clearly important to Schexnider including a soccer ball, a number of stuffed animals, a copy of Chicken Soup for the Soul, an egg cup, and a number of other trinkets, all interspersed with (fake) candles in small red containers. Schexnider arrived into the space wearing a brightly-coloured windbreaker over a 1980s bodysuit, under which were some workout shorts. They were also wearing sneakers which were important for all the movement they do over the next hour. The show begins with Schexnider introducing herself and her family’s history. They grew up in Louisiana, with ancestors originally from Acadia who migrated south to become Cajun. It’s a story that is shared by many other folks. She then launched into a movement and dance section to upbeat remixes of 80s jazzercise audio tracks. Schexnider asked us a couple questions probing our readiness to ‘be our best selves’ and then based on the answers she gave us one of four different audio tracks via a physical tape recorder for me to plug my headphones into. The audio in my ears was a mix of Schexnider’s own voice, recordings from her childhood, and soundscapes. About a third of the way through the show, the audio track playing through my headphones invited me to stand up and explore the space. I was encouraged to move, stand, or sit wherever I liked. My track asked me to applaud for myself, and so I did. I watched a few of the other people around me begin to clap and whoop, garnering looks (more of curiosity than judgement) from the other folks in the room. I laughed out loud a few times and would hear a giggle from the person next to me a few seconds later as they reached the same joke on their track. These little shared moments created a sense of connection and shared experience, even as each of us was on our own individual journey, both literally and physically as each of us wandered the room listening to separate audio tracks through headphones, and emotionally. Even though we are separate in our own audio worlds, we collectively form the congregation for Schexnider’s personal ceremony. It is both a ritual we experience together and alone. You cannot be a congregation on your own. It is, by definition, a group experience. As part of another ceremonial element, Schexnider approached the audience-participants with a small jellyfish stuffed animal. More specifically, it was a Beanie Baby named Goochy, its body about the size of my hand with tentacles dangling straight down below it. As she reached each of us, she shook Goochy in an arc beside my legs, torso, over my head, and then down the other side the same way. At the same time, the audio track playing in my headphones explained that I and my fellow audience members were receiving the blessing of Goochy, and to let her energy heal us. With Goochy, there is no negative energy, and I can feel healed. This section of Holy Moly is reminiscent of the sprinkling of holy water in Catholic ceremonies on the congregation during Easter. As part of Asperges, the Rite of Sprinkling, holy water is sprinkled upon the whole congregation at once with a brush or silver ball on a stick, a symbolic reminder of the more individual ceremony of baptism [2]. Schexnider includes a lot of recognizably religious representations in this work. Chicken Noodle Soup for the Soul serves as her bible. The body of Christ is a meringue instead of the (mostly flavourless) communion wafers or ‘hosts.’ This moment of sprinkling also vaguely reminds me of the practice of sound cleansing that crops up in many other faiths. The ‘csh csh csh’ of the pellets inside Goochy that weigh her down is a soothing, repetitive sound [3]. Schexnider spends a moment like this with each audience-participant. During Mass, the congregation is sprinkled on as a collective by the presiding clergy member, as opposed to the individual ritual we see in Holy Moly, in which we are granted individual attention. At first, I was surprised at how effective I found Goochy the Beanie Baby’s blessing. I think it was something about the repetitive motion with a satisfying sound that gave me and other audience-participants the room to breathe and just exist- almost reminiscent of ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response), the tingly feeling you get in your scalp and spine in response to some sort of auditory trigger [4]. I know that breathing exercises and meditation don’t work for everyone, but I’ve found that it helps tremendously with my own anxieties, so when I was encouraged to take this quiet moment to focus on nothing but Goochy and the positive energy she was bringing, I did exactly that. I keep a lot of my stress in my shoulders and back, and after the blessing I felt those tensions relax. I did some deep breathing, and my heart rate slowed. Visualising that energy transfer while feeling the physical presence of the leader of this ceremony right beside me really helped make it so effective. Schexnider asked me to let Goochy’s energy heal me, and I felt healed. Take this moment out of its context and it becomes completely ridiculous. Shaking a Beanie Baby around my head and torso made me feel at peace? Really? But Schexnider told me this was a sacred moment, and so it was. I felt quite moved by it, and as I watched each of my fellow audience participants have a similar moment, I watched them be moved as well. Devoting time, a hugely precious resource in theatre, to each of the participants makes us feel special. We all crave that sense of care and connection. Schexnider spends so much of this show caring for her audience members so deeply and genuinely. Sometimes when a show spends a moment with just me, that one-on-one attention can feel like I’ve been put on the spot and become stressful and almost embarrassing. In Holy Moly, I never felt that way. Through my audio track I was able to engage and participate in the ceremony, without feeling the need to perform. Schexnider and my fellow audience-congregants felt supportive and open, and I returned that feeling when it was their turn to receive Goochy’s blessing. This show was very open with its invitation. I could get up and dance, or not. I could receive the body of the egg (aka a meringue) or a blessing or simply return to my seat. The option to refuse was baked into its structure. I knew that if I had chosen to say ‘no, thank you’ at any point, there would have been no judgement from Schexnider or the other audience-participants. Schexnider began the show by propping open one of the doors to the theatre space and saying ‘That door? Always open.’ I’ve been to a lot of shows that try to have an exit like this, but it doesn’t always work. If I have to cross in front of a huge crowd as everyone watches me walk out and wonder why I felt the need to leave, it’s not a particularly safe exit. Coming back in is almost worse. I’ve already disrupted everything once and now I’m back to shuffle past and whisper ‘sorry!’ Holy Moly made that option to opt out feel like a viable choice instead of just something they had to stick in at the last minute as an afterthought. Audience safety is clearly a priority. This show was not a conventional performance on a stage for an audience. We as a congregation were there to engage in these rituals and receive blessings. There was no win-condition or even a specific goal we were trying to accomplish. I can’t ‘fail’ a ceremony like I could an escape room or game. The theatre space had been made sacred, and therefore there was a genuine feeling of safety that is often difficult to manufacture in traditional theatre settings. This ceremony worked because of its genuine nature. Holy Moly used these familiar symbols from Catholicism not to belittle those who still practice, but to recognize the power that they have. Schexnider ensured that this was a space that was safe for all audience-congregants to engage in these themes. In his book Audience Participation in Theatre: Aesthetics of the Invitation Gareth White says that ”[t]o expose unconsidered thoughts or emotions in a semi-public space is risky, just as it is to display incompetence, inappropriate enthusiasm, neediness, distress or loss of poise.” [5]. As part of the congregation, I am not on display or part of the ‘performance’. I don’t feel that risk to myself and my reputation that often comes with this participatory theatre. My participation is not part of the spectacle or integral to the show. If I choose to refuse or opt-out of any aspect of this piece/ceremony, it will go on without me and there is no risk of letting down my fellow audience-congregates or embarrassing myself. In Holy Moly, I was a congregant at a service of the Church of Jarin. As congregants-audience participants, we spent the hour-long service/show engaging with Schexnider’s own relationship with ceremony in order to better understand our own connection to it. I was engaging and participating in practices that were sacred to her. This ceremony was a healing ceremony for Jarin that I was invited into as part of my own journey to, as she phrases it, “be my best self.” Schexnider encourages us to confront and examine what that best self looks like and use the show as a guide and prompt to think more deeply. Rituals, by definition, are a series of actions that have prescribed significance. All of the audience-congregants have agreed to engage in these rituals that, by themselves, are meaningless. But because we as a collective have agreed together that these actions have meaning, there is no risk of judgement as we engage with them. What do I take away from Holy Moly? Schexnider has created a ceremony out of holy moments from her own life. I was moved in my participation in her autobiography of holiness, but I’ve also been given a pattern to apply to my own life. Holy Moly reminds me not to take for granted the small moments of ‘holiness’ I can choose to find in the mundane, and to not disregard them no matter how silly they might seem at first glance. If I can find a moment of joy and peace looking at some sparkly dice, great! Taking the time to really enjoy and appreciate my morning cinnamon roll from the local coffee shop can be spiritual if I want it to be. These objects and actions have become more than just generally beautiful or enjoyable; I have the power to ascribe deeper significance to these moments for myself. Going to sit in the coffeeshop and beginning my day with a chai and a cinnamon roll has become a ritual for me; it puts me in a mindset where I am ready to read, write, and work for the rest of the day. It is comforting, but also a sort of ceremony. I am ‘performing’ a series of actions that I’ve prescribed for myself to better prepare me for the work ahead. Religious ceremonies prepare you for the spiritual and emotional labour you will go on to do. They are enacted reminders of what is important and that life has meaning. I might feel that my work is perhaps not so grand-–it’s not flashy to look at and the results are not immediately world-changing— but through ceremony I can assert that it is no less valuable. Works Cited

[1] Schexnider, Jarin. Holy Moly. rEvolver Festival, 29 May 2022, Vancouver, British Columbia. [2] McNamara, Edward. “Rite of Sprinkling with Holy Water.” External World Television Network, 13 February 2007, https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/rite-of-sprinkling-with-holy-water-4358. [3] Ward, Kerry. “Fact: You can totally Cleanse Your Space With Sound.” Cosmopolitan Magazine, 9 June 2020, https://www.cosmopolitan.com/lifestyle/a32800580/sound-cleansing-home/. [4] Lopez, German. “ASMR , explained: why millions of people are watching YouTube videos of someone whispering.” Vox.com, 25 May 2018 https://www.vox.com/2015/7/15/8965393/asmr-video-youtube-autonomous-sensory-meridian-response. [5] White, Gareth. Audience Participation in Theatre: Aesthetics of the Invitation. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. pg 76. #ThrowBackThursday. This post looks back to a live work made by SpiderWebShow’s Adrienne Wong and Mo Horner, Kevin Kerr, and Elki! Although this piece was made a few years back, it acutely speaks to a participatory dramaturgy as a rehearsal and creation technique. Made for the 2019 edition of Theatre Skam’s “Skampede,” Crowd Source is a participatory spoof on a tech demo set in the woods on the Galloping Goose trail in Victoria, BC. I joined artists Adrienne Wong and Kevin Kerr to co-create this piece that aims to imbue participants with a “refreshed” gestural memory by re-embodying classic tech gestures in nature and unplugged. Crowd Source is framed as a cheeky beta-test of new technologies, heavily featuring puns about Twitter feed (bird food), livestream platforms (a bridge over a slow moving ravine), and reboots for a better signal (switching rainboots). The intention was a recognition of the body-as-device and a recognition of the potential that device has to connect with others. In order to beta-test this potential for connection, we needed our participants to volunteer their body-devices for a system upgrade. After we led Crowd Source participants to our “livestream platform,” we invited them to close their eyes as we put on their “VR headsets.” We offered a brief head massage to everyone that gave us permission to do so, then, with nothing on their heads but the tangible memory of a soft massage, we invited participants to open their eyes to take in the Virtual Reality Experience we created just for them. We asked participants to touch their arms and legs, feel their virtual bodies, and notice the detailed stitching of the natural, “virtual” world. We then asked the participants to pick up a “plug-in” (a leaf, free downloads . . . anywhere in the woods) and begin to scroll through their device, imagining what it is they are looking for right now. If permissions were on and the device was set for sharing, they could even scroll through their neighbours’ devices. Finally, we asked the participants to “pair up” for a tethered application offered with the new install. Once they partnered up, participants were asked to focus on their partner’s camera lenses (their eyes) and try to see their own reflection in the lens. Once they found that reflection, participants were instructed not to move for at least 30 seconds so the image could be saved to their hard drive. The piece actively sought an experience of defamiliarization or ostranenie, making the familiar unfamiliar to take extra notice of the characteristics that define an object, gesture, or experience. Crowd Source recalibrates our gestural relationship to our devices by asking participants to embody tech gestures with an ecological bent. By “scrolling” on a leaf or “focusing” on the eyes of a stranger, participants take notice of how gestural memory of technology exists in the body, this time emancipated from the objects the gestures usually populate. Next time participants aimlessly scroll through Facebook, perhaps they will remember the feeling of the leaf on their fingers. With an escalating level of intimacy, we invited audiences to engage with their bodies and physically interact with their neighbours to inspire a reboot in thinking about how we engage with technology through gestural memory. In addition to this being a performance about fictional beta-testing technology, it is itself a beta. And like a true beta-test, Crowd Source changed significantly after it saw an audience for the first time. After the preview, we were told our ten minute piece ran closer to eighteen minutes and we had to make some serious cuts to the text. Before returning to the rehearsal room to start killing our darlings, I was caught off guard when Adrienne approached friends and strangers for their thoughts on what we should cut. From the personal and local experience of embodying the tech demo, participants told us to spend our focus on a cedar leaf because it represents the botanical identity of the province. (Who knew? I definitely didn’t.) One audience member reminded us to have an “opt-out” pathway for those who didn’t want to participate in the entire piece. One blind participant reinforced the need for us to do more thinking about gestural experience without sight. Anti-elitist and definitely connected to the title, this radical audience-dramaturgy, mobilized us to act and we shaved off ten minutes. Audience are not only participants in Crowd Source, they are co-creators. In an excerpt from his seminal Relational Aesthetics, Nicolas Bourriaud believes this kind of work creates an “extraordinary upsurge in social exchanges” and Crowd Source employs these exchanges long before the performance itself. [1] Although there are certainly ethical dilemmas to unpack around repurposing audience labour as dramaturgical insight, crowdsourcing performance and performance in Bourriaud’s writing, is a revolutionary social practice. For participants, being involved in co-creation can be less about conquering a “territory” and more about a symbiotic co-creation. In his articulation of co-design, James Frieze alludes to experiences like Crowd Source, where the “participant is so involved in the making of the work that the distinction between producing and receiving is blurred.” [2] As creators of Crowd Source, we are facilitating their inhabitation more than inhabiting the piece ourselves, clearly blurring the lines between producer and receiver. Their bodies are the ones that are running through the machine; we’ve simply built the machine. If we’re asking participants to inhabit the machine to make it work, why shouldn’t they help us build it? After all, how many times do you hear “try it on your feet” in a rehearsal room? Participatory theatre like Crowd Source opens the door to artists inviting participation at earlier and earlier stages, testing variables and shaping the work in a co-creative fashion. How can we always invite a crowdsourced dramaturgy practice into the creation of new work? Are we interested in that? Miguel Sicart (Play Matters) says that “play is an activity in tension between creation and destruction.” [3] Perhaps why Adrienne invited the audience into the dramaturgy is because it raises to our view the spectre of failure that is always present when creating live theatre, really positioning Crowd Source, from the rehearsal room to the performance, in productive tension between creation and destruction. It became clear that our participants were the dramaturgical experts. An audience member can tell us we failed or offer us a suggestion that causes us to fail, taking the success of the piece out of the hands of the artist even further. Is this relinquishing of artistic control a danger to craft and artists that employ that craft? Do artists risk the categorization of their work as too popular if they employ this structure? Does this degenerate the work itself, shifting the writing room to a kind of corporate focus group, forcing the artist’s to produce what people like rather than what makes them uncomfortable? Or, does it simply acknowledge that the participants are equal stakeholders here and should be treated as such from creation to production? Works Cited

[1] Nicholas Bourriaud. Relational Aesthetics. Translated by Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods, (Dijon, Les Presses du Réel, 2002), 14. [2] James Frieze, editor, Reframing Immersive Theatre: The Politics and Pragmatics of Participatory Performance, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 27. [3] Miguel Sicart, Play Matters (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014), 9. At the beginning of June I took the train to Montreal to catch Manual, created by Adam Kinner and Christopher Willes, at OFFTA. [1] Presented inside Concordia’s Webster Library, Manual largely presented a familiar dramaturgy of participation as we are directed to look, really look. A gift from early-twentieth century Russian formalism, this is the ostranenie of the art frame that uses participation to displace the ordinariness of life. And what is not to love about really looking at a library. You will have to excuse my sentimentality, but as an academic who spends a lot of mundane time in libraries, the experience of aesthetic defamiliarization blossoms into affection and I am reminded by Manual that a library truly is an everyday miracle in action. But apart from ostranenie, what other participatory dramaturgies are at work here? And what do they mean? A couple things that are not happening here. Manual is not exploratory. We are not set loose in the library to choose an autonomous path. [2] I am attached to my guide Christopher. He asks me to silently follow him and I do. The other quality to notice about Manual specifically in my relationship to Christopher is that this is not an encounter (pace Nicholas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics). The intent of the experience is not for us to meet each other. The focus of the work is not autobiographical. It is not about me as me (see Lost Together or 4inXchange) Likewise it is not about Christopher (see Trophy or human library experiences). [3] In addition to remaining almost completely silent which restricts verbal interaction, there is no mutual gaze; Christopher doesn’t look at me. He is either ahead of me or he seems to hover just behind my shoulder. We look at things together but we do not look at each other. Companionable, playmate, but ghostly. To describe Christopher’s function in Manual, Avery F. Gordon’s definition of a ghost resonates for me: “The whole essence…of a ghost is that it has a real presence and demands its due, your attention.” [4] Just as I am not “me”; Christopher is also not “Christopher.” And I mean this in the nicest way. Manual is not about confessing or sharing secrets. (Which is, to be honest, a relief sometimes.) But we are engaged in a kind of intimacy. We are playing a private game in a public space. We are secret weirdos. We are making secrets. The performance begins with both of us looking at a notebook in Christopher’s hand. There are pre-written, penciled messages on a small palm sized spiral bound flip notebook. “Is this thing on?” I follow Christopher silently through the library trailing a metre behind. Initially I am attuned with heightened attention to the library-ness of the library. Look books! (Cool.) We play Follow-the-Leader through the stacks. When Christopher pauses to inspect the bookshelf, so do I. He points to a book title on a spine. (I can’t remember exactly what he picked but it amused me.) I choose a similarly quirky book title and touch it. He picks another one. So do I. Is that what was supposed to happen? Dunno. It is a silent improvisation. Throw the ball. Catch it. Throw it back. This is a very satisfying kind of co-creative partnership. A tiny game for two. As it continues Manual opens other silent creative dialogues. At another bookshelf, Christopher presents a single piece of paper, and invites me to read with him, alternating sentences in whispers. I am wearing earpods and my voice and Christopher’s voice sussurates in my ears and in the auditorium behind my eyes. Next Christopher opens a book of abstract photography and choosing one image, he suggests that we play, you know, that game where you find images in the clouds. “A wrinkled piece of cloth,” he says. “The craters on Mars,” I reply. And so on. In the final section, we take three giant steps backwards and we stand next to each other, facing a shelf wall—the sorting shelf—where books are collected awaiting a return to their proper order elsewhere. The books are a motley mix of all subjects, temporarily companionable side by side. Christopher and I too. He gestures for me to press play on the audio player. As his voice sounds in my ears, musing about the serendipity of books that have been pulled out and read, and then put back, I start to listen. Christopher takes another step backwards and then with a quick shift behind me, he is gone. (I know he is not really vanished, but like the audience to a magic trick my attention has been adeptly directed elsewhere.) Was he even here? Why is the play called Manual? For a theatre scholar, this is always a good question to ask. Certainly, the show is manual, that is, tactile with your hands in a way that much theatre is not. Christopher’s hands are a prominent element in complement to his whispered voice. He flips the pages of his instructional notebook. In another extended scene, he also performs a kind of hand-choreography when he opens for me a series of books, deliberately turning to pre-bookmarked pages and slides sheets of cardboard to hide and reveal portions of the chosen pages. I did consciously remark Christopher’s hands—the skin, the nails, their texture and shade. A manual is also a book of instructions. Thinking specifically through the lens of participation, a manual is a ‘how to do stuff.’ And of course, participation is all about doing stuff. Usually things that we have not done before in places we have not been before. And as we’ve noted elsewhere, participatory audiences need instructions. The contents of a library—fiction and non-fiction—are manuals for everything in our existence, I suppose. The show itself then perhaps is a manual to the manual, an experience in how-to library. This is how you search—first you walk. This is how you choose books—try pointing. This is how you look—really look. This is how you read—let’s read together. Concentrate. This is how you put the books back—notice how they wait so patiently. It is a complete lifetime of libraries in miniature. It sounds trite to say so, since this is true of the accumulation of all experience, but I will never library again without thinking of Christopher, ghost of the library. Notes

[1] https://offta.com/en/evenement2022/manual/ [2] Consider other works in our gallery of participatory performance like Landline or b side. [3] https://humanlibrary.org/ [4] Avery F. Gordon. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. University of Minnesota Press, 2008. p.xvi. The wonderful whirlwind of the Participatory Dramaturgies Summit was beginning to settle in my mind when an email from Mariah rolled into my inbox, seeking some feedback from participants to inform future iterations of the gathering. I was eager to oblige; the three-day experience was delightfully productive for me. I was still buzzing from the ideas that pinged about our virtual meeting space as theatre creators, thinkers, and communicators pondered the unique affordances of participatory art. I quickly answered the first few questions on the feedback form, but a multiple-choice prompt soon stumped me with a relatively simple inquiry: would you prefer an online gathering or in-person? After a moment of pause in the face of this commitment towards virtual or physical, I selected in-person and moved on. Meeting people from my bedroom was convenient, but of course, the pleasure of connecting in a shared space is tough to forgo when given the option. But then I circled back. When I started to reflect on my engagement in the various panel discussions comprising a relatively large portion of the summit, I was forced to contend with the power of the Zoom chat. I know; part of me hesitates to commit “Zoom” to paper due to my more jaded sensibilities. However, on the other side of skepticism is an opportunity to rethink participation in panel discussions and foster digital community creation. Participants from the summit will likely remember the cheeky chaos of the first panel discussion, which saw the chat erupt after the speakers invited us to award them with points based on their contributions. The idea was to gamify the experience, giving the chat control over who would speak based on the overall value of their point totals. The trick: there was no limit to the number of points that could be given. For 20 minutes, the chat exploded as our little audience rebelled, questioned, and used this system to award unfathomable amounts of positive and negative points to see if our influence would manifest anything tangible. The result of this experiment was the creation of a digital community which immediately reminded me of a Twitch stream. [1] The streamers (panelists) focused on creating content while also addressing the chat community comprised of viewers vying for the attention of both the streamer and fellow viewers. Like many Twitch chats, ours was equally unfollowable at times; the feed quickly scrolled by as new comments rolled in, rivalling Lightning McQueen with their speed. I was confronted with the competing choices of listening to the panelists, reading the chat, or formulating a comment of my own. Scholars have explored the implications of fast-scrolling Twitch chats, including a study from Nematzadeh et al. (2019) which labelled this experience as an overload regime: “If the frequency of messages keeps increasing, participants cannot handle the increased information load indefinitely, and so we expect that, past a certain threshold, an increase in information load will correspond to a decrease in user activity. We call this the overload regime.” [2] Indeed, it should be noted that some viewers were absent from the chat, acting as lurkers in the background whose presence was assumed but not demonstrated. Whether or not this was due to an overload regime would be pure conjecture, but I will say that several participants shared a feeling of exhaustion after the panel ended. None of the other panels would reach that peak level of chat activity over the next few days; this was perhaps for the best, given the challenging cognitive load carried by such an experience. However, I’m grateful that the first one ignited our participatory spirit and cemented an engagement with the chat community. In the end, participating in the Zoom chat was one of the biggest positive takeaways for me. It was satisfying to see others engage with my comments or ideas, and I learned just as much from the group’s responses as I did from the speakers. Resurfacing that Twitch connection, I’ll point to an ethnographic study from Hamilton et al. (2014) completed during the early days of the streaming platform’s rise to prominence, which found that one of the main benefits of participating in the chat was sharing: “Another common reward is the gaining of knowledge and skills available from other community members. In stream communities, this often takes the form of game skill and knowledge, which may be uniquely available from the streamer or their viewers.” [3] I similarly felt that I was taking advantage of the expertise of this found community, and the trading of knowledge made the act of participating in the chat rewarding. Some may worry that the chat could be a distraction, but in my own experience as a panellist, I found the chat to be more of a help than a hindrance. Fielding live questions from audience members with a microphone or from the panel mediator can be stressful because there’s less time to sort through ideas and articulate answers on the fly. In contrast, the digital chat allowed me to read questions from the crowd ahead of time, meaning thoughts could percolate in the back of my head before answering them. The chat also allowed for more direct bridging between the speaker and the crowd by offering opportunities to respond to the concepts and comments raised by viewers. I recall seeing a discussion about Overwatch [4] in the chat pop up during my panel that I happily addressed due to my interest in the game. Sharing my main character of choice and some thoughts on the meta took less than 30 seconds, but in doing so, I was able to contribute to community growth through a personal connection. In another Twitch parallel, the chat also had a dedicated moderator as Jenn and Mariah traded panel and chat mediation duties. In Twitch, moderators can ban viewers if they post offensive comments, but they also serve as facilitators of participation. The same Hamilton et al. (2014) study mentioned previously found that “the role of moderators is not only to keep the discussion in line, but to engage viewers and promote participation and sociability. This most often involves greeting viewers, answering questions, and trying to connect personally with newcomers”. [3] As panel chat mods, Mariah/Jenn similarly responded to comments from viewers, asked questions and fostered this secondary discussion as necessary. The use of chat moderation helped legitimize the textual conversations and combat any fear that a comment would be disruptive or unwelcome. Under their guidance, the chat community thrived. And so with all of this in mind, I returned to the question: would you prefer an online gathering or in-person? Don’t get me wrong, physical gatherings are lovely, and I would jump at the chance to flex my small talk skills and fully loaded dad-joke humour. However, in the face of mounting evidence, I moved my cursor and changed my answer. For a participatory theatre summit, I simply couldn’t resist the immediate participatory potential of the digital chat community and the relationships it built between panellists and viewers alike. Notes