|

Rebecca Draisey-Collishaw and Kip Pegley

It’s been more than a year since we heard news of the novel coronavirus, now ubiquitously recognized as Covid-19. And just over a year since much of the world found themselves with some version of a stay-at-home order. Since the beginning of 2021, the news has been full of anniversary reminders of the profound moments that have drastically altered the ways that we live and our capacities to interact. Indeed, it seems likely that one-year memorials will thematize our experiences in 2021. While many of our remembrances are woven with grief, anger, loss, and loneliness, with April 7 upon us it’s perhaps worth recalling the anniversary of a gaff-turned-sensation that brought laughter, inspired dialogue, and built community solidarity. In this blog post, we’ll explore how the DIY aesthetics and the figure of the prosumer (audiences that actively and interchangeably consume and produce content) muddy the waters between content creators and audiences and necessitate a revisioning of what it means to participate in the public life of a nation.

During the first 110 days of the Covid-19 pandemic in Canada, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau provided almost daily updates from the steps of his home (learn more about Trudeau’s almost-daily Covid-19 updates at https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/110-days-81-addresses-to-the-nation-what-pm-trudeau-s-covid-19-messaging-reveals-1.5019550). On April 7, while describing measures each of us should take to hinder the spread of the virus, he uttered the now-infamous—and infinitely cringe-worthy—advice that we should avoid “speaking moistly” on each other. Trudeau’s original announcement had a massive audience: CBC’s English language services, for example, reported an average reach of 4.4 million television viewers and 1.9 million radio listeners for the PM’s morning updates during this period of the pandemic. And those numbers only include people who tuned in via CBC; the actual audience more than doubles when other broadcasters and coverage in both official languages are considered (https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/grenier-pm-press-conferences-1.5587214). It was a verbal gaff with legs of its own that evoked laughter from audiences, comment from pundits, and elaboration by artists. Indeed, one of those artists gave Trudeau’s utterance wings when he transformed the speech into a music video with danceable beats. On April 8, 2020, Brock Tyler (known by the username anonymotif) released his version of “Speaking Moistly” on YouTube. It was a runaway success that defied his expectations and went viral overnight. Tyler’s version of Trudeau’s speech takes the form of a “meme song,” a composition that involves creatively combining and remixing memorable video and audio, usually with the purpose of offering commentary on a person, moment, or concept. Meme songs exist and circulate exclusively via social media. Tyler's “Speaking Moistly” uses techniques like zoom, delay, slow motion, and quick cuts from the news footage of the PMs address to splice together a music video that follows the simple song structure. The song itself is an autotuned manipulation of Trudeau’s speech, which is underlaid with electronic effects, drums, and synthesized harmonies.

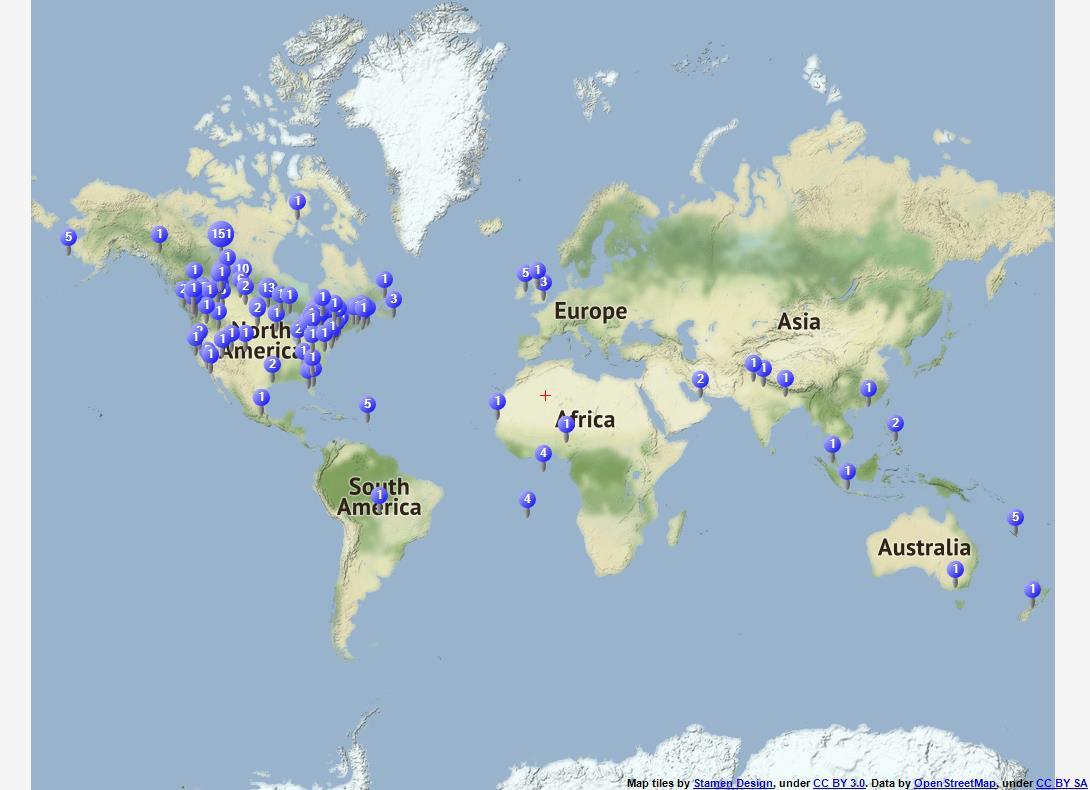

Within 24 hours, the music video received more than a million views. And a map of 1,393 Twitter tweets that appeared between April 18 and April 28, 2020 and featured #SpeakingMoistly shows that by the end of the month the song had been shared throughout much of the world.

The viral popularity of “Speaking Moistly” on social media was covered in traditional media, with the result that Trudeau’s words effectively hung around in the media cycle longer than could otherwise be expected, reaching an ever-expanding audience and building a shared rhetorical vision centred on Trudeau’s pandemic management. This rhetorical vision could then be maintained, elaborated, and contested through the participation of prosumers in digital spaces. As Tyler later reflected:

I think that the statement itself had enough behind it in terms of comedy that we probably would have seen a fair bit of that […] in terms of the slogan living on t-shirts. But I think the song just made it kind of hang around in people’s consciousness a bit longer. (interview with author, 23 September 2020) In other words, what Tyler’s meme did was promote spreadability via social media platforms (like YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, etc.) and, after initial successes, via a licensed audio-only version of the song to Spotify and iTunes. The relationship between audiences, memes, and Web 2.0 technologies is at the heart of that spreadability—and the meanings that emerge as messages traverse across off- and online spaces. A phenomenon of social media, meme songs complicate how we think about traditional roles of creator, performer, and audience. Social media is a form of participatory culture that erases distinctions between (active) producers and (passive) consumers, instead relying on the figure of the prosumer (producer + consumer) to both create and engage circulated content. In the case of “Speaking Moistly,” Trudeau may have authored a memorable phrase, but his image and words quickly transformed to source material for creative elaboration by others. Tyler was a pivot between on- and offline spaces, and the embodiment of the prosumer: he was an audience for Trudeau’s speech, creator of an artistic/parodic meditation on a “very Canadian” moment, and, ultimately, a source of material for subsequent elaborations by other prosumers. Legitimizing mainstream politics

At first glance, Tyler’s meme comes across as a parodic public service announcement (PSA)—and much needed moment of levity in a period of crisis. It was comedy with a familiar feel for many Canadians. After all, political parody has a long history in Canada.

Parody is a form of humour that exaggerates the familiar aspects of an original text by, for example, caricaturing a person’s looks or comments, all without judgement (cf. Young 2014). This form of political humour is common fare in a plethora of CBC comedy shows (ranging from somewhat to heavily political) that have aired over the decades. These include, among many others:

Scholars of comedy describe parody’s function in rallying public opinion and humanizing political figures (e.g., Jones 2009: 44). Memes can fulfill a similar purpose, but their user-generated origins validate an “official” message in a cultural context that increasingly doubts the veracity of politicians and experts (cf. Parlett 2013). Youtuber comments about “Speaking Moistly” seem to support the capacity for parody to rally public opinion, humanize, and affirm Trudeau’s pandemic management efforts. As one person commented, “I love it. Trudeau has a good sense of humour he saw it and laughed too. So cute.” Another viewer added, “Love him more than ever!” A more critical voice (who identifies as proudly Conservative) tweeted, “And yet still Trudeau can't speak English. But let's cut him some slack #speakingmoistly takes great lip dexterity.” While unintentional, “Speaking Moistly” may have helped mitigate partisan divides during the strictest period of pandemic restrictions (to date) in Canada. Producer vs/and consumer

There’s a necessary distinction that must be drawn between the parodies produced in the official contexts of the CBC and the user-generated memes that circulate over social media. Comedies like Royal Canadian Air Farce or 22 Minutes might contain skits—or even music videos—that are markedly like “Speaking Moistly” in their approach to poking fun at politicians. However, the assumptions about creators, audiences, and the direction of communication are quite distinct, even irreconcilable.

Audiences for shows like the Rick Mercer Report, for example, are expected to passively consume content (and hopefully be informed about important issues). Information, in other words, flows from creator to audience. The participatory culture that is the norm in social media spaces, however, presumes that audiences are also creators—that consumption begets new content and popularity involves more than a high rate of views. That is, the flow of information is multidirectional, with almost limitless potential for engaging and reinterpreting source content. Reacting to the popularity of “Speaking Moistly,” Tyler explained: When I was working on it, I really had no expectations at all. And to see it sort of slowly build momentum and then […] it just sort of takes off and it's out of your control now and you see the sharing happening in real time and it's sort of like this avalanche of social media activity and it's addictive at first because it's so fun to see people enjoy something you made. […] I think what was neatest about it, and one thing I certainly didn't expect [was] for people to do covers of it. […] I had to keep the song really simple because I was doing it so quickly. And I really didn't think through how I was going to do it. I basically went with every first idea I had. And it ended up being a song that was simple enough, melodically and chord wise, that people could cover it. And so to see that first cover come out, which was […] an acoustic cover and there were a few that kind of came out at the same time, like ‘oh that's so cool.’ I just had no expectation that people would want to embody the song and make their own version of it. (interview with author, 23 September 2020) Tyler went on to explain that when he creates meme songs he is concerned with the fidelity of his representation; he’s interested in highlighting the humour of the moment, but he doesn’t want to put words into anyone’s mouth by splicing and reordering original statements (interview with author, 23 September 2020). And yet, consider Tyler’s words: “it just sort of takes off and it’s out of your control.” The meme, the image, the music, and the message have the capacity to move, reinforce, and reinvent meaning almost infinitely. Politics in an age of controllessness

Politics and communications scholar Martin A. Parlett asserts that:

Online activism in vacuo is nugatory—the flame of social media revolutions is sustained by the oxygen of offline action and cultural participation. Presidential politics is still governed by votes counted at the ballot box and not the number of blog posts or retweets in a candidate’s favor. Broadcast still plays an important role in consciousness shaping, just as the doorstep or back fence persist as the more important sites of political persuasion. (2013: 134-5) Writing on the role of social media during the 2008 presidential campaign in the United States, Parlett further contends that “participatory culture is Janus-faced” (2013:152) and that Barack Obama’s successes in this domain emerged, in part, from an appreciation of the “controllessness” social media engagements. While Obama successfully mobilized his base through Web 2.0 technologies according to a positive shared rhetorical vision, the opposition created a countervision that was just as powerful. That is, for each message Obama released into the world, each online engagement contained the potential to be read and recirculated as confirmation of an oppositional worldview. For Parlett, online activism only becomes politically effective when it begets offline engagements, with prosumers fluidly moving between domains of engagement and fueling opportunities for further participation. “Speaking Moistly” is illustrative of an online engagement with offline consequences: the viral popularity of Tyler’s meme on social media meant that millions of viewers received well-informed public health advice that helped rally the population in a period of crisis. But as Tyler himself points out, audiences didn’t just watch, share, and comment on “Speaking Moistly.” Like Tyler, they were prosumers who participated in making meaning by using his meme as a source for their own shareable creations. The resulting profusion of Tiktoks, YouTube videos, Instagram shares, and Tweets is so vast as to defy categorization. They include:

There is a tendency to focus on social media as a source of disinformation and the embodiment of the worst qualities of humanity. We all have a responsibility to engage critically with the content that circulates through our various feeds. But focusing only on the capacity of Web 2.0 platforms to circulate fake news or radicalize individuals to anti-social ideologies perhaps gets in the way of appreciating what the controllessness of this medium means, and how we might leverage the performative opportunities that emerge when the lines between creators and audiences blur beyond distinction.

Rebecca Draisey-Collishaw completed her PhD in ethnomusicology at Memorial University in 2017 and held a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Dan School of Drama and Music, Queen’s University from 2019 to 2020. Rebecca co-edited the Yearbook for Traditional Music (2018) and curated the Irish Traditional Music Archive's digital archival exhibition, A Grand Time: The Songs, Music & Dance of Newfoundland's Cape Shore (itma.ie/newfoundland). Her research, which focuses on intercultural musicking and public service broadcasting in multicultural contexts, appears in MUSICultures (2012), Ethnomusicology Forum (2018), Contemporary Musical Expressions in Canada (MQUP, 2019), and Music & Politics (2021).

Kip Pegley is a Professor in the Dan School of Drama and Music, Queen’s University and a researcher with the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research. Pegley is the co-editor of Music, Politics and Violence (Wesleyan University Press, 2012), and, more recently, their work on sound and trauma has appeared in Singing Death: Reflections on Music and Mortality (Routledge, 2017), Music and War in the United States(Routledge, 2019), and MUSICultures (2019). Sources Patricia Cormack and James F. Cosgrave. 2013. Desiring Canada: CBC Contests, Hockey Violence and Other Stately Pleasures. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Jeffrey Jones. 2009. “With all Due Respect.” In Satire TV, ed. Jonathan Gray, Jeffrey Jones and Ethan Thompson. New York: New York UP. Martin A. Parlett. 2013. “Barack Obama, the American Uprising and Politics 2.0.” In Social Media Go to War: Rage, Rebellion and Revolution in the Age of Twitter, ed. Ralph D. Berenger, 133-167. Spokane, Wash: Marquette Books. Dannagal G. Young. 2014. “Theories and Effects of Political Humor: Discounting Cues, Gateways, and the Impact of Incongruities.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication, ed. Kate Kenski and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. https://www-oxfordhandbooks-com.proxy.queensu.ca/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199793471.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199793471-e-29?rskey=haFjSw&result=1

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed