|

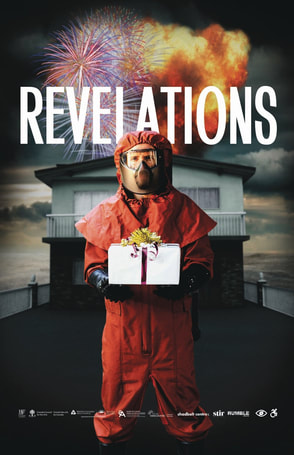

#ThrowBackThursday. In this post, I’m reminiscing on the show Revelations created by Toronto-based theatre creators Anahita Dehbonehie, Griffin McInnes and Aidan Morishita-Miki which I saw just over two years ago at the Kick and Push Festival in Kingston, Ontario [1]. I saw this show in the summer of 2020. At that point, we had stopped wiping down all our groceries and fully isolating from the public, but we were still unsure of whether we’d be heading back to campus in the fall. The only people I talked to unmasked were my roomates - everyone else I hung out with exclusively digitally. Enter Revelations: a game wrapped in a show about the apocalypse, but not the one that we were living - the potential future nuclear apocolypse. The day before the show, a man in a hazmat suit knocked at my door. I knew that he was coming of course, he was dropping off some of the materials my group would need for the game the following day. In this package was a walkie talkie and some papers with game components clues. He placed the package in front of my door and then stepped back across the street. He asked me a couple questions via his own walkie talkie - if the power went out right now, what would I have for dinner? Did I have people I could go to? I could tell he wanted me to start thinking about what I would do if a major apocalypse was upon us. He thanked me for our conversation, reminded me of the instructions I was to follow the next evening and then left, hazmat suit swishing as he walked away. During our scheduled show time, my bubbled roommates and I gathered at a table in our backyard. We spread out all the things in our box on the table. In addition to the walkie talkie, there was also a series of clues that would eventually lead us to the meet up location for the second part of the show along with some papers that explained the rules and other game mechanics. By talking to other groups in their own household bubbles around Kingston via walkie-talkie, we had to decide what mode of transport each of us were going to take to escape nuclear fallout: car, boat, or on foot. Due to numbers, the best decision for the group would be the boat. The more people that chose the boat, the better odds of survival each of the boat-groups would have. For this show, those odds of survival were represented by a roll of the dice and the more people that picked boat meant the more dice those people had at the end of the night in their attempt to survive. It was an exercise in collective care or individual risk-taking. The sticky part comes with the car; if one group picked the car, that group had much higher odds of survival (i.e. many more dice). If more than one group selected the car though, they would have to play a game of rock paper scissors to determine who would get it. The losing team would have to walk and therefore have next to no chance of survival (you rolled one die). There were also some other factors to consider. In our boxes were also some pieces that were specific to each group - for example, one group had a piece of paper that let them know that if there was conflict between their groups that resulted in more than one group choosing the car, they would be granted an additional die. Another group was granted an additional die if all five groups chose the boat. Communication by walkie talkie was perfect for this show - narratively, it is a low-tech solution that would work when the rest of the technological ecosystem collapsed. They are also, for many of us, a relic from a time when we were younger. I know I associate walkie talkies with running around the woods with my cousins during the summertime. It also meant we had to choose to talk, as opposed to phone calls or video calls- those are open channel of communication where turning away and talking to your group is the active choice, instead of pressing the button to share with the rest of the groups. When you are at an in person participatory or game-based show, you have to turn away and whisper to not be overheard, whereas the walk talkie meat that secret conversations within your group is the default. They also add to the distancing effect for this section of the show. My group spent most of the walk to the second part of the show talking about what we thought about the other groups and what the gathering we were heading to might look like. At that point the only information we had was the location, Confederation Park in downtown Kingston, a perfect setting for this section of the show. In actuality, you could walk, drive, or take a boat to and from it. Once my group arrived at Confederation Park, we did a couple laps before we stumbled upon what looked like a party being set up. There was a table with what appeared to be a DJ, lots of lights, some balloons as markers for where each household should stand for social distancing purposes and a large table with cupcakes, chocolate and vanilla. We were told that the cupcakes were the reward for the ‘survivors’ (in the end that just meant that the winners got first pick; we were all invited to take one once the show had concluded). Also arriving at the meeting place was a group of households that had done part one of the show with each other the day before. As other folks started to arrive, guilt started to creep into my heart. This was a game, and the real-life consequences were nil, but seeing these people instead of just hearing their voices made them so much more real. In his book Post Dramatic Theatre, Lehmann says, “Theatre takes place as practice that is at once signifying and entirely real. All theatrical signs are at the same time physically real things.” [2]. As audience members, we become scenography, aesthetic parts of the show, as well as practical ones- within the diegesis of this play, our lives are on the line, and our betrayal endangers the lives of others. On one level, I know that there is no actual risk of bodily harm in Revelations, especially not from a nuclear apocalypse. And yet, I still feel the ‘realness’ of this show affecting me. All the physical stress markers showed up- I felt my pulse quicken with each new group that meant we were getting closer to beginning the rolling of the dice, and my palms were starting to sweat. My fellow audience-participants were not actors, they were exactly like me. Similarly, we were playing a game that simulated the end of the world while living right in the middle of a global health crisis. Once again we see the world inside and outside of the fiction of the play begin to collide. It was much easier to know the ‘right’ thing to do in the game than it was in our real lives and real international emergency. Eventually, the same man I had talked to the previous day strolled to ‘centre stage’ (i.e. in front of the DJ table) and announced into his microphone that we were going to begin the next phase of the performance. After yesterday’s cohort had all gone, our show’s groups were invited, one representative per group at a time, to roll their dice and determine their fate. My roommates, chickens that they are, nominated me immediately. When it was our turn to reveal that we had chosen to take the car, no one looked surprised- we found out afterwards that our walkie talkie had some technical difficulties and they could all hear our scheming when we thought they couldn’t. C’est la vie! Unsurprisingly, we ended up losing the rock paper scissors battle for the car against the family standing next to us and had to walk away from the apocalypse. Eventually, it came time for me to roll our die. I thought about blowing on it for luck but decided that wasn’t the best idea during a global health crisis, and so I picked them up, put all the positive energy into it that I could muster and rolled. I can’t remember exactly what I ended up getting, but I do remember that it was not enough: we did not survive the nuclear apocalypse.

At its core this show was asking us what we valued more, the individual or the collective? Participation is, by definition, not something you can do alone. And yet when we look at the inspiration for this show we see so much individualism. Doomsday preppers create bunkers for themselves and their loved ones, preparing for the day when a natural disaster, economic collapse, or nuclear war means that it’s everyone for themselves. In it’s sim, Revelations asks us to confront our own approach to the end of the world; it offers us valuable lessors in collective care that can be applied easily to our real world. My relationship to my fellow participants changes over the course of this show, the gap between us closing as we come together in a shared space. The novelty of congregating like this was only magnified by the months of social distancing we had adhered to at this point. In her book Utopia in Performance, Jill Dolan says “Audiences form temporary communities, sites of public discourse that, along with the intense experiences of utopian performatives, can model new investments in and interactions with variously constituted public spheres.” In this case, we are actually engaging with almost the opposite of what she calls utopian performatives, which are “small but profound moments which performance calls the attention of the audience in a way that lifts everyone slightly above the present, into a hopeful feeling of what the world might be like if every moment of our lives were as emotionally voluminous, generous, aesthetically striking, and intersubjectively intense”. Revelations askes us to perform dystopia, as we rehearse for the apocalypse. Still, Dolan’s ideas on the choice to gather in a public space prove relevant, especially at the height of pandemic anxiety. We were performing one kind of apocalypse in worldB as we tried to navigate a different one in worldA. Works Cited

[1] Dehbonehie, Anhita, McInnes, Griffen, and Morishita-Miki Aidan. Revelations. Kick and Push Festival, 31 August 2020, Kingston, Ontario. [2] Lehmann, Hans. Postdramatic Theatre. Routledge, 2006. [3] Dolan, Jill. Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater. University of Michigan Press, 2005.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed