|

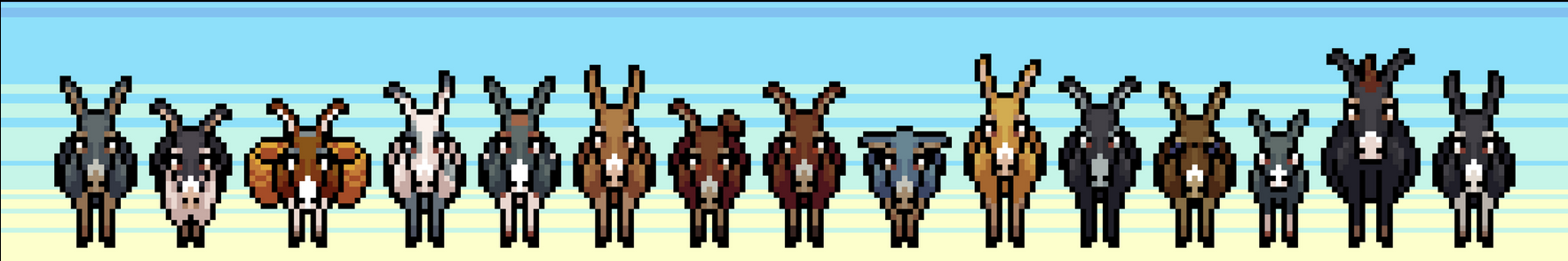

with writing from Jenn Stephenson, Mariah (Mo) Horner, Derek Manderson, Charlotte Dorey, Benjamin Ma, Bethany Schaufler-Biback, and Jacob Dey Created by Patrick Blenkarn and Milton Lim with dramaturg and touring producer Laurel Green, sound designer and composer David Mesiha, digital artists Clarissa Picolo, William Roth, Ariadne Sage, and Samuel Reinhart, [1] asses.masses can be simply (but perhaps reductively) described as an eight-hour video-game theatre experience. The show was presented at the Festival of Live Digital Art (FOLDA) in Kingston on 8 June. The plot of the play-game follows a herd of asses from Fannyside Farm who contemplate the value of their labour in relation to humans and to machines. Over the course of ten episodes, eight-hours and an uncountable number of ass jokes, we take turns playing as the donkey avatars (being the asses) and shouting out (usually helpful) advice (being the masses). Given that a core dramaturgy of the show is what its creators call the “politics of the basement,” where we take turns either playing the video game or sitting on the (metaphorical) couch heckling and encouraging the current player, we thought that a similar serial approach to writing about the show seemed appropriate. (“ASS POWER!”) Several people who participated in the Kingston show have generously shared their thoughts here. We’ve selected some excerpts from their writing. If you want to read more, follow the links below each section. Mariah writes, “Duration allows for participants to settle into this community, to take off their socks and share snacks. Duration allows for time to negotiate turn taking and role playing without too much pressure. Duration gave me the time to consider picking up the controller and then ultimately decide against it. Duration gave the hecklers the space and validation that sometimes shouting out ideas is a type of team playing. Duration also allowed for the sort of chaotic unraveling of our theatrical tendencies…. As shown in asses.masses, duration has the potential to both generate and destroy. We could grow as a herd while we shed our theatrical tendencies around sitting still and being quiet. We could create community and destroy the passivity of the spectator.”

Jenn writes, “I was curious as to how often the controller would switch hands. This is a key nexus point of social negotiation by the audience-herd. Who will lead and for how long?… I realized here that precedent is powerful. The first person played the whole first episode and after that each subsequent person also completed the whole episode. There were a few attempts to hand off the controller mid-episode, but the offer seemed feeble and any potential taker didn’t move fast enough to make their desires to play known before the current player resumed. There is also potential for more frequent changes of possession of the controller. For example, taking turns playing the mini-games or allowing a more “expert” or agile player to navigate a difficult sequence. Of course, this question of who leads, and the changes of leadership is central to the plot of the show. Obviously, there are asses and we are the masses. Different asses assume leadership of the herd at different points in the narrative.”

Derek writes, “I’m someone who loves to participate. I also love games. I think I’m pretty good at them too. But I found myself quite anxious about stepping up to claim the controller and take the lead…. I had several supporters who encouraged me to stand up each time there was an opportunity for the player to switch. Yet I remained glued to my seat, tied down by an invisible force of insecurity. So, why did I feel this way? The social pressure was a big factor. In the latter half of the performance, it felt to me as though there was significantly less patience in the room. We had built a rapport as a group which included a fair amount of shouting. We had grown familiar enough with the game for audience members to confidently become backseat gamers. At this point, I’m not sure people wanted to see a fellow audience member play the game, but rather, for them to serve as a physical conduit for progressing the story. There is a distinct pressure when individual performance is responsible for group progression. What if I couldn’t do something right? What if I made a bad decision?”

Charlotte writes, “Sending an audience member up to that podium is a sign of trust, and that faith creates a sense of responsibility to the “herd” that is extremely affective for the audience player. To step up to the front and agree to make decisions on behalf of the group is a brave thing. Still folks seemed to get bolder over the course of the show’s duration and more went up as the show neared its conclusion. It doesn’t take that long to build a sense of community, and as a collective we quite quickly set a tone where folks felt comfortable shouting out suggestions and tips to the player at the front. They may have stepped out of the audience physically but they are still one of our own. Even though the controller is in their hands, we are working together.”

Bethany writes, “Without the presence of a performance rep for the production outside of the game itself, audience members were required to look to one another to learn the norms and expectations of our temporal collective. This proved to be fairly successful as demonstrated by the repetition of events, how the game would start after intermission, how much time an audience member would spend at the controller, how mini games were approached became predictable. We established our own ‘etiquette’ that was abided by throughout the entire 7.5 hours. I think this is largely attributable to the value of the positive affects within the audience collective. Working towards a common goal, achieving a mini game and moving forward felt good and was cause for celebration. Through the various chants that arose out of audience inside jokes created as the game progressed, I became tied to the positive affects experienced through my body as a result. I didn’t want to act out of turn or against our communally decided government as not to disturb the positive contagion within the audience, holding onto an affective glue which supported our government. I would assume that this was felt by other audience members as well.”

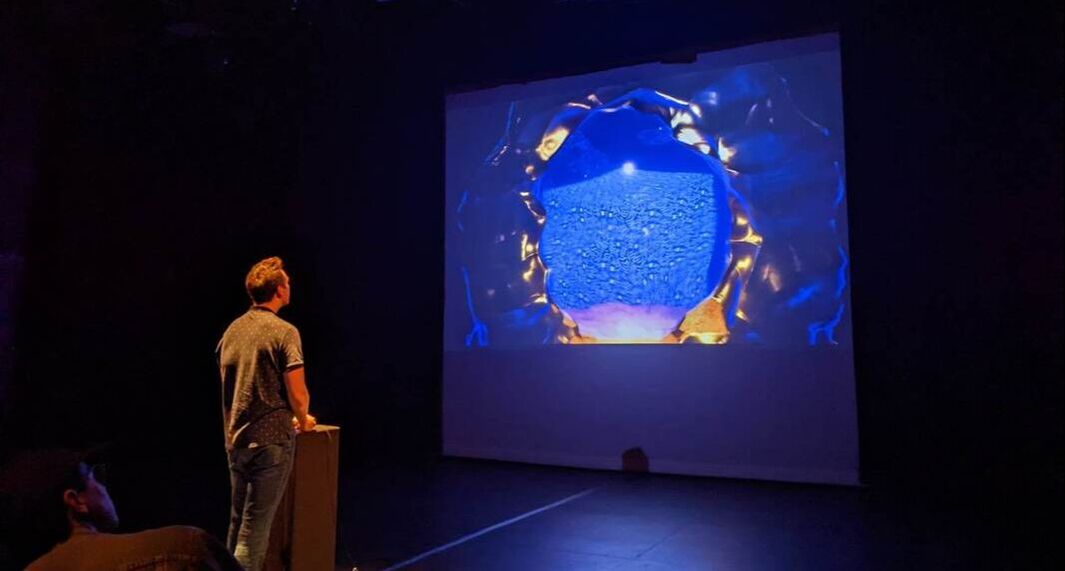

Benjamin writes, “The physical configuration of the room allows a player to step forward from the herd, as Thespis stepped out of the chorus, to assume the position of the ass who will lead our journey. Once they assume the position, they are voluntarily stepping into a position of alienation as their backs are now to the audience and the top and side lights create a barrier between them and us. . . . By the end of the night, I felt as though something had shifted within the audience. What was once a group of strangers remains a group of strangers, yet there will always be a sense of familiarity to them; a familiarity dictated by a game, and established by the bravery it takes to separate from the herd and speak on our behalf.”

Jacob writes, “Thought #5: I'm a theatre kid, I do not shy away from attention. I do not want to grab the controller. I do not want to be subject to 40 backseat drivers. I press the x button to end the intermission and sit back down. Someone else can do the work.” READ MORE.

Stay tuned for where asses.masses will be next by checking out their website and following them on socials. [1] Although not featured in the version of asses.masses we saw at the Festival of Live Digital Art (FOLDA) in Kingston, the show also features a Spanish translation done by Marcos Krivocapich.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed