|

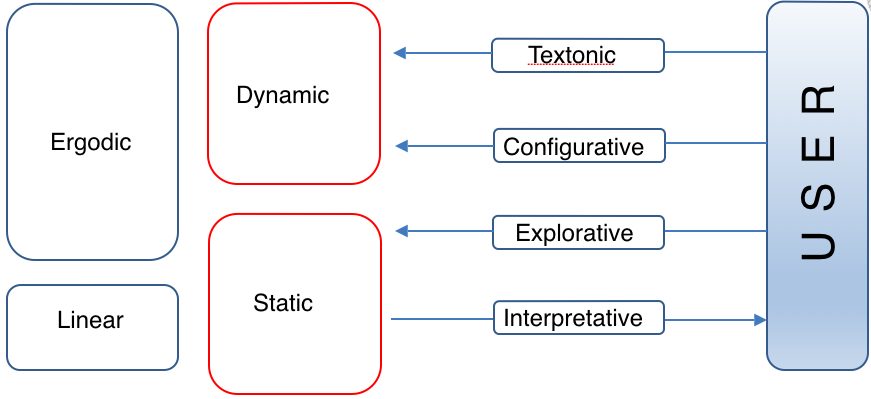

One of my delights (I know . . . “geek alert!”) is to take a piece of critical analysis that is either outmoded or from another discipline and see what happens when it is applied to a current performance text. In this case, the “old” work is Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature by Espen J. Aarseth written in 1997. What is ergodic literature? Good question. This is a new word coined by Aarseth from the Greek root ‘ergon’ meaning to work (Think, using the rowing machine at the gym as “erging”) combined with ‘hodos’ meaning path. The choice to add path to work says a lot about the nature of the texts he is thinking about. Cybertexts or “ergodic” works are texts in which the reader makes choices about the direction they wish to follow. 1980s kids’ lit Choose-Your-Own-Adventure books work this way. As does a more consciously literary work like Michael Joyce’s (1990) hypertext novel Afternoon. Aarseth also includes early digital games and MUDs (multi-user dungeons/domains) and the I Ching among other things. What I love about Aarseth, writing in the mid-1990s, is that he has no idea what is coming next. The provocation that Aarseth provides to thinking about the work of path-choosing by the ergodic audience of participatory performance is I think best summed up in this diagram from page 64. In this early phase of our research into participatory performance, this four part taxonomy has been very useful as a kind of litmus test to describe in basic terms the different performances in terms of labour. In Aarseth’s terms, “What is the user’s function?” In our terms, “What is the work that the audience-player is doing?” The first function in Aarseth’s diagram is “Interpretative.” I am glad to see this here. This notion that the hermeneutic work of the audience in discerning meaning is active labour is important. Interpretation as active work lines up with the central thesis of Susan Bennett’s seminal work Theatre Audiences (1990) which looks to reader-response theory to demonstrate the centrality of the audience in actively creating meaning in the intersection of their experience of the work and their own unique archive of knowledge. Is interpretation participation? Another good question. Trying to answer this question has been critical to helping us to refine the territory of this study. (Another reason why Aarseth has been useful.) Our current take on this is to say, “No.” Interpretation is active and it is work. But is it “taking part?” And this is where we are starting to build the parameters of what counts as participation for our study. The act of participation is engaged in personal meaning making but it is not an act of co-creation. The work is not materially changed as a result of my interpretation. Perhaps we can say it is active but not interactive. The second listed function in the diagram is “Explorative.” Audience workers in this mode are seekers and navigators. They are curious investigators. Exploration might be as minimal as being mobile, walking along a single path and choosing where to look. Or the space might be expansive with lots of latitude for determining your own path. In this mode, scenes might come in any order or some scenes might be skipped entirely. Each audience experience is an entirely unique self-directed artifact. However, audience impact is quite limited insofar as the environment itself and any associated narrative remains essentially unchanged by the audience-players. Popular examples include haunted houses, mazes and audio-walks/podplays. Tamara written by John Krizanc, which premiered in Toronto in 1981 before touring to New York and Los Angeles is one of the earliest examples of this kind of work. More contemporary examples include Brantwood (created by Julie Tepperman and Mitchell Cushman) and The Archive of Missing Things (Zuppa Theatre). The constructive function describes audience-players who contribute to the making of the performance somehow. Aarseth describes the gaps to be filled as keyholes where the audience is holding the key. Often the audience is not just ‘holding’ the key but the audience IS the key. Audience provide their bodies as physical labour—in Counting Sheep, we disassemble a trestle table and benches to create a protest barricade. Audiences also provide their bodies as scenography or supernumeraries—in It Comes in Waves we are all party guests. Audiences also provide immaterial labour through answering questions or revealing autobiographical details. This happens in Foreign Radical where we are repeatedly asked questions pertaining to our online privacy and our behaviour at border crossings to evoke our ethical consideration of government security surveillance. Aarseth’s fourth category is “Textonic.” Here he is accounting for those moments in literary works where the reader becomes a writer and contributes a new “texton,” or chunk of text. This is different from the gap-filing work of construction. New sections are created de novo, and the work becomes unpredictable and emergent. Anything (well, almost anything) could happen next. It is rare for performances to be contingently emergent like this in their entirety, but there are moments. Moments where the opportunity for audience impact is significant and strongly shapes what comes next. Storytelling in Lost Together is emergent. It is known that Shira and Michaela will make a miniature sculpture in response to the audience’s story of a lost object, but exactly what that sculpture will be is entirely indeterminate. Similarly, the blindfolded guessing game/hide and seek in The Stranger 2.0, not only is the framework very loose but the performance is responsive to input in a meaningful way. What we are discovering is that these categories get a bit blurry, especially between construction and emergent responsiveness. Moreover, in a single performance audience members may perform some or all of these functions simultaneously or different moments in a work may invite different kinds of work. This taxonomy derived from Aarseth is hardly the final word on audience work but it has provoked much fruitful analysis as we have attempted to describe and sort the work of participatory work.

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed