|

I first became aware of the luminous artwork of Anne Louise Avery when she started to appear on a regular basis in my Twitter feed, retweeted by a friend. Avery, who from her Twitter bio, is writer and art historian, based “mainly” in Oxford, perhaps a professor at the university there. Each day Avery posts a tweet where she creates a short poetic vignette based on an assemblage of three images. Usually one of the images is a photograph of an animal, a fox, bear, otter, mouse, or similar. The other two images might be paintings, a landscape scene (rural or urban) or an object still life, typically but not always in a late 19th century/early 20th century fin de siècle style. In a reply to her own tweet, Avery provides citational references listing the title, creator, and provenance of the works that she has chosen. The vignettes themselves personify the animal depicted as they often pursue human activities like baking scones, serving tea, playing draughts, digging in the garden, or catching the train to London, writing in a journal. Each tweet garners upwards of 600 likes. Clearly, Avery has a devoted following. I too followed @AnneLouiseAvery through January and February. To say the vignettes are charming does not do them justice. They are tiny evocations of joy, of melancholy, of friendship, of a kind of wistful quiet happiness. They are beautiful. I admire the craftsmanship that Avery invests in these gems. They lift my heart. After a few weeks, it became apparent to me from some other tweets Avery interspersed with her artworks, that she was tending to a sick child in hospital, her son, not very old, the diagnosis uncertain. Then, around the end of February, Avery’s Twitter feed was inundated by dozens and dozens of tweets created by her followers that replicated (as best they could) her own poetic and visual style. It was an outpouring of solidarity, of love from strangers, and sincere wishes for her son’s recovery and her own well-being in a time of personal crisis. Social media has often attracted this kind of spontaneous expression of community. But what struck me here as worthy of comment is that rather than just a message, Avery’s followers gave her back her own art as gifts. They collectively chose to communicate via participation as artists. They appointed themselves responsive fellow creators in her own special mode, sometimes using some of her own characters and mimicking her voice, as an homage to what she and the work mean to them. What is remarkable is that this art became participatory. It was not participatory from the outset. It evolved. Social media created the basic conditions of possibility, first for Avery to share her visual poems with hundreds of strangers, and second for that community of readers to cohere with a common mission, themselves becoming artists of affectionate reflection. In Twitter parlance, “this is the content I’m here for.”

1 Comment

TW: confinement As a self-identified nut for participatory and immersive work, I am floored it took me this long to see Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More. Set in the sprawling McKittrick Hotel in NYC, Sleep No More is an immersive movement-based funhouse adaptation of Macbeth and in fall 2019, this research project finally afforded me the opportunity to catch one of the most commercially successful immersive performance in the world. After dinner and drinks with a friend, I headed to Sleep No More alone. My friend refused to give me anything besides a reassurance that knowing me, I’d love it. I wasn’t afraid of going alone, I was told this was the way I should consume this piece anyways. When I enter the McKittrick Hotel, I am given a white mask and a playing card. While I wait for my number to be called, I am invited to purchase a cocktail. Once my number is called, I enter an elevator with twenty or so other players and I meet my first and only explicit guide. He lays out the rules:

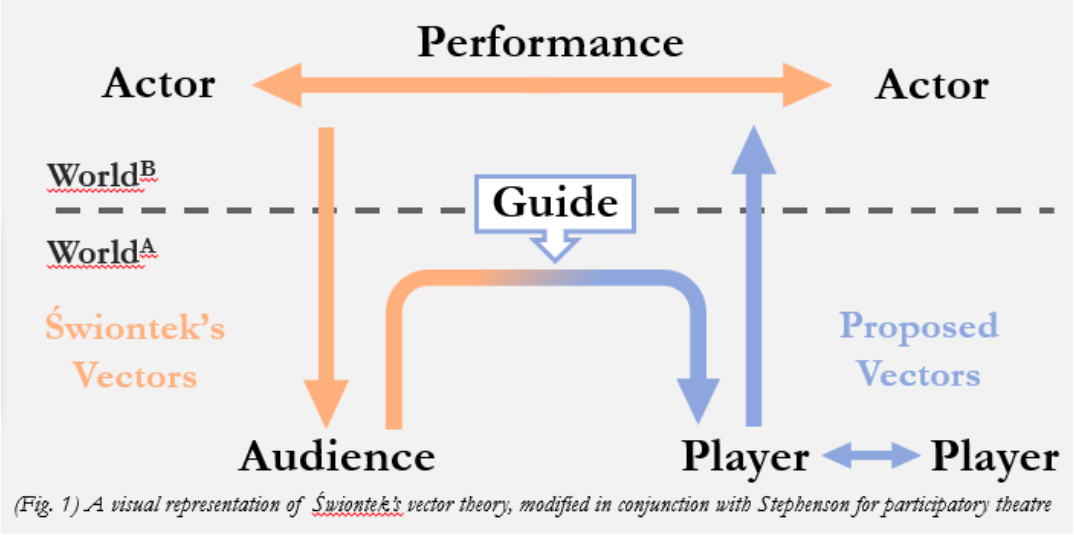

He then encourages players to “be bold,” and kicks us off the elevator, free to independently roam the sprawling 6 floor hotel. I’m giddy at this point, ready to explore and happen upon a secret. I wander around some rooms, poking through drawers, dipping my hands in tepid bathtubs and daring myself to open every door I find. About fifteen minutes in, I still haven’t seen any actors. I wander all the way to the top floor and find myself in a room that looks like a hospital ward with 12 or so beds in two rows. I notice that under one bed, there is a man doing a stylized movement sequence. I’m joined by another curious woman and because we can’t see his face or his mask, we wait and watch. He emerges from under the bed with his white audience mask on backwards revealing his face. Then he gestures for me and the woman to follow him and he slides his mask back on, concealing his face. The adventurer in me is ecstatic. Not only have I found an actor to follow, but he’s incognito. He’s an actor, posing as an audience member. I boldly follow him around the hotel. Myself, the incognito actor, and the other woman enter a small study. He closes the door behind us. He takes a lab coat off the wall, puts it on the shoulders of the woman I am with, and sits her in a chair. He touches the middle of her back, doubling her over her knees. This happens three more times. Then, he bolts and I run after him. For the rest of the night, I lose him and then find him again, staring at me from across the room under his audience mask. He waves at me as I chase him through crowds, up and down stairs, and into closed rooms. Then, he blows through a door that was clearly a backstage door and because of the reaction of the folks in black, who promptly eject him back out again, it dawns on me. This man wasn’t an actor. Suddenly embarrassed, uncomfortable, and unsafe, I leave Sleep No More 45 minutes early. My experience was spoiled in a particularly sinister way because this audience member preyed on me when I was told to follow my nose and explore dark corners. In her book Performing Ground, Laura Levin says at her first time at Sleep No More, she was “less disconcerted by the eerie music, taxidermied animals, and bloody bodies than finding myself in a room alone with a bunch of masked men given license to do whatever they wanted” (Levin, 84). Yup. “Be bold,” the man in the elevator tells players. I wrote to Sleep No More detailing this experience but no one got back to me. On the subreddit r/sleepnomore, there are fanatics who detail potential tracks to guarantee a one-on-one with an actor. On Gawker one can learn “How to Find All the Nudity in Sleep No More” In a Buzzfeed expose about Sleep No More, actors detail abuse they experienced from audience members during the show. It is disturbing. Some artists we have studied categorize their work as “ambient performance,” work that exists inside a worldA that is visible and continues to turn outside of the narrative. Zuppa Theatre Co’s This is Nowhere functions this way, as an audience roams around downtown Halifax constructing a blueprint for the future. The excitement of wondering “is this part of the show” reframes and animates the regular world inside and outside of the frame, This is an exciting kind of work for a participatory audience. The audience can control how they explore, what they look for, and what trail they are following. There is an additional energy behind discovering what is intentionally constructed and what is happening IRL. However, my experience at Sleep No More also tells me that this feeling can be anxiety inducing. When Laura Levin recounts her own experience in Sleep No More, making reference to these blurred lines between “reality and illusion” and the “explicitly sexualized” kind of “voyeurism” that the show encourages, she quotes Director Felix Barrett saying that Sleep No More tries to “‘make the audience the epicentre of the work...so they can control it’” (Levin, 83). But in this case, I was controlled by someone else. This audience member co-opted and hacked Sleep No More to play his own game, using the free environment to craft an experience in parallel with the intentional experience of the creators. Many of the case studies that encourage ambient exploration invite this kind of choose-your-own adventure reception. Think mirror mazes, ball pits, and parks. Children often play like this by using the given circumstance of a space and inventing their own game. Grounders works exactly this way. In Sleep No More, this freedom to play means “be bold” and many aspects of the show’s design encourage, perhaps dangerously, this kind of play - masks, darkness, being alone, vast space, non-linear plots, and alcohol. Freedom fosters innovation. This person in Sleep No More played an alternate game. This is different than opting out. “Hacks” like these are layered on top of circumstances provided by the artist. In Landline, some folks hack the performance to text their scene partner for the entirety of the experience, rather than listen to the audio prompts provided. Both Archive of Missing Things and This Is Nowhere encourage free exploration that is not limited to the explicit goals of the work. The difference between those hacks and what I experienced in Sleep No More was interference. This man took advantage of my curiosity. He put me at risk and affected my experience. Where some work invites a kind of choose-your-own alternative adventure, this person chose my adventure for me. Works Cited Levin, Laura. Performing Ground: Space, Camouflage and the Art of Blending In. Palgrave Macmillan. 2014. If you were to purchase a video game today, there’s a good chance you would open the case to find a disk and a promotional pamphlet. Notably absent is the rulebook, practically archaic nowadays with the prevalence of gaming culture and the perceived decrease in attention span. Who has time to read a whole book? With enough prior knowledge, the game should be easy enough to figure out as you go. Theatre similarly comes packaged without a rulebook because, of course, we already know how to play the role of the spectator. We know when to applaud, when to be silent, and most importantly, we stay in our seats. Alexander García Düttmann remarks that “it belongs to the rules of the game of art” that one does not interfere with the stage proceedings, and there can be great comfort in accepting the ensuing action is out of our control. However, participatory theatre flips on the house lights and throws the audience a controller. It’s time to become a player. While exciting, this position is often a vulnerable one; as we shed the familiar skin of passivity in favour of agency, we are forced to question the expectations placed on us in this new role. What am I supposed to do? How can I be a “good” participant in this event? What if I do something wrong and ruin the game? The risk of embarrassment or failure often generates apprehension in would-be players. Janet H. Murray raises some parallel concerns about risk inside fictions in her book on immersive game-play, Hamlet on the Holodeck, exploring how we can “regulate the anxiety intrinsic to the form.” As she notes, “suspense, fear of abandonment, fear of lurking attackers, and fear of loss of self in the undifferentiated mass are part of the emotional landscape of the shimmering web” (135). However, we are not doomed to remain lost at sea as we navigate the murky waters of participation. Emerging to answer the outcry for help is a new theatrical role which accompanies us on our journey, gently pushes us onto a safe pathway and critically, teaches us the new rules. Enter, the guide. Much like how Navi accompanies Link in the iconic game The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, the performative guide exists to ensure the success of the player. As an adaptive role that shifts in appearance and design with each show, the guide can appear in a variety of forms. This is unsurprising given the evolving nature of participatory theatre’s structure and content; however, I posit that in successful participatory performances the guide consistently surfaces to combat the player’s risk of failure. In Monday Nights, the guide appears in the form of a coach who encourages audience members to become active figures in a basketball game. The potential for embarrassment here is strong, especially with spectators who feel unathletic or uncoordinated. In this instance, the guide builds a supportive team environment that celebrates participation and minimizes risk through unconditional cheering. By eliminating insecurity, audiences can grapple with the purpose of their participation and appreciate both the value of teamwork and the bonding nature of the game. Tape Escape, though entirely different from Monday Nights in its construction as a participatory experience, also utilizes the guide to great effect. In this video store escape room-performance hybrid, groups of players are accompanied by a store employee. As a natural guide, the employee utilizes an intimate knowledge of the space and an approachable nature to assist when necessary. With puzzle solving at the forefront of the experience, frustration and the risk of offering incorrect solutions can plague players. This poses a significant problem because the story is revealed through each solution, and as such, the performance exists in the interactions between the players and the space. Therefore, an inability to navigate the surroundings directly relates to a lack of progression in the show. Here, the guide steps in to mitigate the difficulty level by providing hints and store insight when players are struggling. Much like a real store employee would assist customers in finding DVDs and offering recommendations, the guide facilitates a meaningful experience for the players. Though the focus remains on the player’s wit and relationship to the unfolding story, the guide alleviates the appropriate amount of pressure to provide a rewarding challenge. Although the form of the guide may change, the role is unified by the widening of theatrical directions of communication. Thinking about communication and metatheatre, Sławomir Świontek first proposed that we understand theatre through “vectors” of performance that carry information. These “meta-enunciative vectors” run perpendicular to each other; one is actor-to-actor (or character-to-character) inside the fictional world, the other crosses the so-called fourth wall, sending information to the audience. Fig. 1 demonstrates how participation modifies these “vectors” by allowing players to send information back, establishing a communication loop between actors and participants. The guide hovers on the line between the actual world of the audience and the fictional world of the performance, which Jenn Stephenson identifies as “worldA and worldB,” respectively. In Monday Nights, we recognize the guide is a coach both within the play and the world of the audience. We already expect guidance from this figure, and so the facilitation of participation is natural. The same can be said for the store employees in Tape Escape, who offer players excellent customer service. In both cases, the guide exists and behaves exactly as one might expect in our world, while also playing a role in the evolution of the performance. The guide approaches the audience in worldA, and once a familiar relationship has been solidified, the transition into worldB becomes possible. The key here is that the guide is not the central figure, but a role which encourages the audience to become active figures themselves. It is through this transformation, and only through this transformation that participatory performances can create the biggest experiential and dramaturgical impact. I hope that as participatory theatre continues to grow, the guide will prevent paralysis from the risk of participation by facilitating meaningful play that is equal parts entertaining and aesthetically satisfying. We all have the capacity to be players, we just need a little help to play the game. Works Cited Griztner, K., and Alexander Garcia Düttmann. (2011). “On Participation in Art.” Performance Research, vol. 16, no. 4 (2011): 136-140. Murray, Janet H. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. New York: The Free Press, 1997. Stephenson, Jenn. “Meta-enunciative Properties of Dramatic Dialogue: A New View of Metatheatre and the Work of Slawomir Świontek.” Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, vol. 21, no. 1 (2006): 115-128. Świontek, Slawomir. Excerpts from Le Dialogue Dramatique et le Metathéâtre. Translated by Jenn Stephenson, Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, vol. 21, no. 1 (2006): 129-144. White, Gareth. Audience Participation in Theatre: Aesthetics of the Invitation. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. *This research was generated as part of a University Summer Student Research Fellowship (2019) funded by Queen’s University. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed