|

We are overjoyed to announce the inaugural play/PLAY: Participatory Performance Summit! Taking place from 7-9 April 2022, this summit is an invited gathering of artist-creators and scholar-researchers of participatory performance in Canada. As the first “event” imagined by the team behind play/PLAY, the summit will be hosted by Jenn Stephenson and Mariah Horner with support from production manager Dylan Chenier and stage manager Christina Naumovski. Our goal is to offer summit participants a space to meet and talk with other artists and researchers, present work, and participate in engaging debates on participatory performance. The intention of the summit is to bring together a select group of artists and scholars who share an interest in participatory theatre events in an interactive gathering. By participating in the virtual summit over Discord, participants will have the opportunity to:

Why are we doing this? First, we’re eager to get the artists from our gallery and the writers from our reading lists in conversation with each other. Over the last four years, while we were collecting and analyzing over 70 participatory shows in Canada in an online gallery, we were simultaneously researching and writing a scholarly book on participatory dramaturgies. As we continue to populate our gallery, we realize we’re watching a community of real experts in the field creating and thinking in real time. We know you, you know each other. Plus, everyone has been so open with us! Strangers are answering our cold calls, artists are sharing archivals, and scholars are sharing nascent ideas in interviews. We have felt a great sense of camaraderie and generosity from the artists and scholars in this cohort and it’s time to bring everyone that we have learned from and with together. As we continue the project of writing this book on participatory dramaturgies, we are excited to put our own principles into practice and participate in conversation on these topics together. Besides the fact that we believe this group simply needs to connect with each other, we are eager to experiment with conference structures during the summit. During a conference panel about participation and immersion in 2020, artist and friend of the Summit Alex McLean wished that all panel talks started after the introductions and biographies. He put his finger on a desire of both artists and scholars to spend more time looking deeply at our participation practices together, moving beyond surface descriptions of our own work, and instead getting into connections and extensions. We are eager to open a space for these artists and scholars to grapple with shared issues and interests. After two years of the COVID-19 pandemic and resultant social isolation, we have felt a real need to play and disrupt in a collective. Because we both work at the intersection between artist and scholar, we know about the value that comes from deep analysis and a dynamic creative commons. At this time, participation in the Summit is fully subscribed, but if you would like to learn more, please email us at [email protected]. Check out some of our confirmed participants here and read more about the summit here.

0 Comments

A very common point of focus in participatory theatre performances is on the singularity of the audience participant. I’ve written elsewhere that a recurring marker of certain types of participatory theatre is that it is not only created by me (through my participation) but also for me and about me. [1] The pull to autobiography is strong. And you can see why. If the audience-participant is asked to do something or give something, all they have immediately at hand is themselves—their physical labour, their ideas, their opinions, their ability to solve puzzles, their personal history, etc. In a show like Lost Together, autobiographical play is crafted by and for a solo audience member. In 4inXchange, we share autobiographical details in a small group of four. Even in larger audience groups, like TBD or Foreign Radical or Intimate Karaoke, although we might be surrounded by others, the focus of my experience still solidly lies on me as an individual. My placement in relation to the participation of the others is sometimes serial and sometimes parallel but in every case we are separate. This, however, is not the case in two recent participatory performances I witnessed. Instead of the personal focus of participation as autobiography, in these shows we are amalgamated, we blend together, we are interchangeable, we are a collective. Our individuality is purposely effaced. My self as self is irrelevant. The first of these shows is Saving Wonderland. Presented online as part of the Next Stage Festival, Saving Wonderland blends dramatic storytelling with choose-your-own-adventure decision making and escape room puzzle-solving. The show uses a range of tech platforms including live-action Zoom broadcast, audience chat, and a game app for our phones. The premise of Saving Wonderland is that when Alice visited Wonderland previously she broke it somehow—time is looping and the storyworld is disintegrating— and only Alice can fix it. What is central however is that all of us in the Zoom audience are collectively Alice. There is only one Alice and it is us. The characters address us as Alice. When presented with a puzzle to solve or a choice to be made, we use the game app which works like a poll. The majority vote determines our choices. Similarly, for the puzzles or other digital tasks, if most of the group gets the right answer, we are successful. It is entirely possible to do the show as a disparate assemblage of pure majority rule. On the other hand, on the night that I participated, a leader emerged in the chat and directed our voluntarily coordinated responses, saying “Let’s pick the Red Queen.” or “I think the answer depends on a Fibonacci sequence.” (I, for one, was happy to follow Jackson’s lead. He always knew the right answers.) Either strategy is fine, but whether we remain aloof or choose to consult, the app operates to funnel our input into the oneness of Alice. [2] (The app game task where we each have to mash the on-screen button as fast as we can but without going “over” speaks especially strongly to our role in an invisible collective.) The other show with a similar collective audience character and mode of participation is David Gagnon Walker’s This is the Story of the Child Ruled By Fear. [3] The play is a poetic fable of the journey of the eponymous character of “the child ruled by fear.” Here, a small number of audience participants, (perhaps six or eight people) sit near the front at cabaret tables each equipped with a reading light and a script marked with highlighted section. When their turn comes, each of these participants joins in to read a character. The creator, Gagnon Walker, serves as the Narrator. Audience readers play different characters but also significantly they all, at different times, give voice to the Child. The rest of the audience is also invited when cued to become a chorus. My favourite speech of the chorus is: “We are real. We are real. We are real.” The effect of this collective reading is perfectly described by the show’s promotional blurb which describes the experience as “a playful leap of faith into the power of a roomful of people discovering a new story by creating it with each other.” And so it is. The suggestion emerges that at some point in real life Gagnon Walker might be the child ruled by fear, but then through our dispersed and collective voicings so are we all. We all have fears and sometimes we can be brave and sometimes we can’t. The play evades a simple answer. Nevertheless, the true outcome is that in the end, we have all partaken in a collective journey to create something that we don’t know how it goes, and we journey together with generosity for the risk of participating. The result is a kind of vulnerable rough beauty. Notes

[1] My article “Autobiography in the Audience: Emergent Dramaturgies of Loss in Lost Together and Foreign Radical” is forthcoming in Theatre Research in Canada 43.1 (2022). [2] Spoiler alert: The ending for my play-game experience (which was different from Mariah’s) returning us all as Alice to a blue-sky morning on the riverbank before we ever meet the White Rabbit and before the start of the events of the book Alice in Wonderland. We are told by the Cheshire Cat that the only way to really save Wonderland is for us not to enter in the first place. (See blog post from on 19 July 2021 being unwelcome.) This is emotionally bittersweet but also astonishing in terms of game play and participation. Essentially we are being told that the way to “win” is not to “play.” (!!) We do not belong in Wonderland. [3] Mariah and I were all set to fly to Calgary to see this show as part of the High Performance Rodeo festival in January when the Omicron variant of COVID caused all live performances to be canceled. The creator very generously shared an archival video with us. Roger Caillois (Man, Play, Games) identifies the randomness of chance or what he calls “alea” as one of four core categories of games. [1] In opposition to ‘agôn’ or games of skill that engage players in direct competition, alea involves no skill at all. Both agôn and alea are premised on equality; but whereas equality in agonistic competition is about fairness in the rules so that either player has the same chance of winning, equality in alea manifests in contingency putting the players in the hands of fate or the universe. The player in a game of chance is entirely passive and whatever happens happens. The only determinate action the audience-player makes is the decision to begin to play and then subsequently to end play. In between, active choice is between random, superficially identical options - do you go through the door on the left or on the right? - or the choice is to activate the randomizing mechanism, rolling the dice, or similar. The choice is heartless. As Caillois writes, “It grants the lucky player infinitely more than he could procure by a lifetime of labor, discipline, and fatigue. It seems an insolent and sovereign insult to merit.” [2] Either the audience-player chooses directly in this kind of desultory fashion or defers choice to a non-human participant. The morality of gambling as an affront to the Protestant work ethic and possible social damage of addiction aside, it is worth thinking about how choices with unpredictable seemingly random outcomes generate aesthetic understanding since this is a common dramaturgical strategy for shaping participation. How does alea mean? The audience plays the game but we are merely the conduit of fate. We spin the wheel but choice is external; the mechanism is the dominant driver rather than the player. The universe is the playwright. This feeling of passively ‘letting it ride’ can be pleasurable if the stakes are low and the attitude not too existential. Sometimes the effect is a hopeful sense of being safe in the hands of Providence, that things are as they should be. Sometimes, by contrast, being subject to randomness is a desolate peek into the abyss; we are adrift in an uncaring universe. Nothing matters. In the Dungeons & Dragons themed participatory show Roll Models, [3] randomness manifests in the repeated rolling of the dice. Just as in the table-top role-playing version of the game, the dice operate in this “live action” version to determine the outcome of an audience-player’s asserted prospective action. “I will cast a spell to throw a magic net on the dragon.” Roll an “8” and you are successful. Roll an “18” and perhaps you not only avert the danger but you may also be rewarded when the dragon becomes a friend and ally. Roll a “4” however and you might find yourself in the net instead. Part of the improvisatory narrative skill of the performer who acts as the ‘Dungeon Master’ host character is to interpret the raw number generated by the dice, translating that information into context-specific (also usually absurd and hilarious) dramatic exposition. Greg Costikyan in his book Uncertainty in Games notes that among the sources of uncertainty (performative uncertainty of player skill, puzzle solver’s uncertainty, hidden information, and so on.) randomness, which many players despise, has some particular strengths, notably “it adds drama, it breaks symmetry, it provides simulation value, and it can be used to foster strategy through statistical analysis.” [4] Actually, the dice are a pretty good substitute playwright. Perhaps the possible message here is simply a reminder of the unpredictability of the universe. It is a truism that even the best plans, enacted by highly skilled characters might fail, or conversely, the unconsidered shot in the dark by an unprepared novice might succeed. Humans also introduce randomness into participatory performances. Another way that contingency appears is as a branched narrative or experience. For example, Monday Nights is actually four plays in one. The performance is divided into four strands from the very outset when the first task of each audience member is to inspect the contents of four gym bags. From these autobiographical assemblages, I pick whose team I want to be on. In the moment of choosing, the other three branches vanish. Others will follow those paths but they are closed to me. I can see the other teams across the court but I watch from the outside and cannot access their experience. This melancholic regret of the path not taken is always embedded in any choose your own adventure schema. In Monday Nights, the dominant feeling is a sense of belonging, attachment to my captain and the other audience-players who made the same choice. I am on the red team. Do I wonder what it is like to be on the blue team? Perhaps a little. By contrast, the regretful wonder of what might have been is the principal theme of Outside the March’s play Love Without Late Fees (Tape Escape). The central conceit is that the immersed audience is running a video store dating service called “Six Tapes to Find the One.” A series of escape room style puzzles activates the branching mechanism. Audience choice is indirect. Successfully solve the puzzle and rent Mr. Holland’s Opus and our couple Matt and Sarah do one thing. Fail to solve the puzzle and rent The Shawshank Redemption and Matt and Sarah’s relationship takes a different track. The effect here of alea in the creation of thirty-two unique endings is to remind us that the journey of a love relationship can indeed feel like an exercise in serendipity. If this or that hadn’t happened we wouldn’t have met. Randomness is a life quality that we recognize. Love relationships are really like this sometimes. And so the flip-a-coin branches replicate a real-world situation. The audience then plays the role of “the universe”; our puzzle games are part of a superior ontological realm that somehow determines the romantic fate of the would-be lovers. This game mechanism stands in as a simplified parallel for the impossible-to-comprehend complexity of the world. The impossible-to-comprehend logic of the universe made manifest in games of alea is adapted in Foreign Radical to comment on the Kafka-esque arbitrariness of bureaucracy, specifically the all-powerful surveillance of border control. Badgered by a maniacal game show host, the audience-players are compelled to answer revealing questions with public actions, dividing ourselves into four corners of the room based on yes or no responses. “Have you watched online pornography in the last twenty-four hours?” “Have you signed a petition critical of the government?” “Do you use encryption to mask your internet use?” “Do you own a pressure cooker?” The answers to the questions are not random; they are autobiographical confessions. But the consequences of the answers are random. Based on their answers, certain members are banished out of the room. Is this a reward or a punishment? Do I want to go there or stay here? The underlying value system is purposely opaque. We are at the mercy of a game we cannot comprehend, unsure if we are winning or losing. Beyond game structures that mimic the contingency of choosing this or that to create meaning, the basic situation of audience participation is a prime source of randomness. In her list of reasons that drive participatory art, Claire Bishop notes that not only does participation create a more egalitarian or democratic base for creative engagement, there is an aesthetic benefit in the greater unpredictability of input via audience contributions. The benefits from greater diversity of randomness as well as the pleasures of surprise and serendipity are held in balance with reduced coherence resulting from less artistic control. Participatory works built as a series of one way gates or are “on rails” manifest relatively low randomness and relatively high control. One way to provide guardrails is by providing the audience-player with a script. In the case of shows like Red Phone and Plays2Perform@Home (both produced by Boca del Lupo, Vancouver), there is literally a script. In Red Phone, the audience-player enters a standalone red telephone booth. Inside the booth is a teleprompter-style screen and a red telephone handset. Talking to another audience-player in a second, somewhat distanced phone booth, the two of you perform a scene, voicing dialogue. Within the tight parameters of the scripted task, each version of the experience looks (at least from the outside) nearly identical. Meaning lies in how the players, now transmuted to actors/characters, collaboratively navigate both the fictional relationship unfolding line by line in real time and the real-world partnership of smoothly making a thing together. Works that incorporate improvisation, by contrast, feature high randomness and low control. Dice are not the only source of alea in Roll Models. Although there is a traditional audience, four audience members are invited to become role players. Each one creates a fantasy-adventure style character; they are paired with an actor who plays that character and who is effectively their live avatar. Through their role-play quest, the players make choices and declare their intentions, (with success or failure determined by the dice) the actor-avatars are challenged to realize those actions. In this way, Roll Models centrally locates the values the randomness of audience input as the catalyst for its core understanding. Costikyan notes that not only are endings uncertain in games (unlike in drama) but the journey to that ending is also uncertain. “Uncertainty is in the path the game follows, in how players manage problems, in the surprises they hold.” [5] It is precisely that this grappling with uncertainty is the source of pleasure in Roll Models. The audience-players are randomness generators; they are part of the game mechanic generating ‘friction’ for the actors. They are basically more sophisticated dice in human form. The appeal of the show then, and indeed its raison d’etre is to generate joyful laughter not only at the absurdity of the ad hoc plots but in the virtuosity of the actors as they frolic in unpredictability. In the secondary audience, we thrill to the successful struggle in their performative acrobatics to respond to the unexpected twists of the plot and to bring it all together (somehow) in the end. Their victory over the obstacles of alea is our delight. Works Cited

[1] Roger Callois, Man, Play, and Games, Translated by Meyer Barash (Urbana and Chicago, University of Chicago P, 1961), 19. [2] Caillois, Man, Play, and Games, 17. [3] Roll Models was presented 18-26 August 2021 in City Park, Kingston ON. The show was conceived and performed by Alicia Barban, Joel Blackstock, Tyler Check, Callum Lurie, and Sayer Roberts. [4] Greg Costikyan, Uncertainty in Games, (Cambridge MA and London: MIT Press, 2013), 86. [5] Costikyan, 13. CW: colonial violence As thousands of unmarked graves of children who were held captive at Canada’s residential schools were unearthed in July 2021, Dr. Alan Lagimodiere, the new Indigenous Reconciliation and Northern Relations minister in Manitoba spoke publicly for the first time. In this speech, Lagimodiere says, “the residential school system was designed to teach Indigenous children the skills and abilities they would need to fit into society as it moved forward.” At the time, many white settlers in so-called Canada were finally unlearning this dangerous lie, grappling instead with the truth that this state-sponsored educational institution had explicit goals to “kill the Indian in the child.” Wab Kinew, the leader of Manitoba’s NDP, interrupted Lagimodiere, approaching the podium saying, “I am an honourary witness to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I listened to stories of the survivors and I cannot accept you saying what you just said about residential schools.” More than listening to testimony, being an official Honorary Witness to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) comes with an active commitment to tell the truth about colonial violence in so-called Canada. “Witnesses were asked to retain and care for the history they witness and, most importantly, to share it with their people when they return home.” [1] Notably, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation asserts witnesses must commit to participating in a future where the genocide of Indigenous children is not forgotten or misunderstood. Kinew’s active interruption and correction of Lagimodiere’s narrative illustrates this commitment to participation that includes the destruction of false narratives. While Kinew’s intervention did not occur in an explicitly theatrical context, it serves to illustrate the participatory capacity of performing witnessing as an act that changes both the participant and the world. Historically, some theatre theorists have articulated both the potential and outcome of this act of bearing witness as an activist element of being a spectator. Sometimes this activism is framed in moral or educative terms. In the introduction to his 18th century play The Robbers, German theorist Friedrich Schiller articulates the power of bearing witness as a preparatory practice for avoiding vice. Schiller says, “if I would warn mankind against the tiger, I must not omit to describe his glossy beautifully marked skin, lest owing to this omission, the ferocious animal should not be recognized until too late.” [2] For Schiller, theatre provides the space for audiences to safely bear witness to a metaphorical tiger, so that they will be ready for the dangers of immorality they will meet in real life. For Kinew, Schiller’s tiger is the testimony he heard. Where Schiller only expects action in the outcome when he shows his audience the “tiger,” witnessing as a dramaturgy of participatory theatre encourages action from the moment you first meet the testimony or the tiger. As a witness to the TRC, Kinew heard testimony with the intention that he is prepared to fight for (in Schiller’s case, against) what he heard. So, how exactly can this witnessing act be theorized as an active invitation into the future? Indigenous writer Samatha Nock unpacks the subtle differences between listening and witnessing. Nock insists that “too often we think that the act of listening is equal to the act of witnessing.” [3] She describes listening as a passive endeavour. By contrast, she says that when we “witness a story we are not only present physically, but emotionally and spiritually, to hold this story in our hearts.” When we witness a story, “that story becomes a part of us,” and “you have entered a very specific and powerful relationship that exists between the storyteller and the witness.” [4] Witnessing is an active and ongoing invitation to participate in relation, it’s a contract between the witnessed and the witness, signed by the act of hearing testimony. For our colleague Julie Salverson, a scholar of witnessing, “to be a witness, I must find the resources to respond. It isn't only passing on a story that matters; I must let the story change me. This makes me vulnerable in the face of another's vulnerability. I participate in a relationship. But to be present in a relationship, I must have a self to offer. Tricky territory. Who, right now, has the nerve to reveal themselves?” [5] Salverson also asserts that “courageous happiness” [6] is a resource to activate witnessing. Where Nock names the agreement as “relational,” Salverson says that “witnessing is a transaction that is personal, social and structural.” [7] Salverson cites the work of Roger Simon and Claudia Eppert who claim that witnessing “demands (but does not secure) acknowledgement, remembrance and consequence. Each aspect presents different obligations.” These three moments of witnessing: acknowledgement, remembrance, and consequence are a map of activity from which participatory witnessing is charted. Acknowledgement is the awareness and confirmation of what is being witnessed. Remembrance “commits a person as an apprentice to testimony.” [8] As an apprentice to testimony, the witness agrees to be employed by testimony; an apprentice signs a contract as a novice committed to work. Remembrance marks the changing of the witness. The third term, “consequence,” is about obligation, about what we do with the knowledge we perhaps wish we did not have.” [9] Consequence marks the changing of the world. This is what Kinew does when he steps forward to speak. Trophy, a work of solo storytelling, created by Sarah Conn and Allison O’Connor, materializes this three-part path of witnessing as theorized by Nock, Salverson, Simon and Eppert and exemplified by Kinew’s interruption. Marketed as “an episodic performance and living installation built around stories of transformation,” [10] audiences of Trophy are invited to roam through a “pop-up Tent City” of simple white tents. Each tent features the live recitation of an autobiographical story from a person in the community who experienced great change. After audience members listen to the stories of transformation, they are invited to write their own stories of change on coloured pieces of paper and attach them to the tent. “How the installation evolves is determined by the public’s interactions with it,” [11] Conn and O’Connor say. This visible and participatory manifestation of witnessing, I hear your story and it changes me (and the tent!) means that “the experience of Trophy becomes an expression of all participants’ stories, and a compelling exploration and conversation about how we all experience change.” [12] Witnessing is a core participatory dramaturgy. Bearing witness is a participatory dramaturgy that signs a deal to continue to participate beyond the show. Witnesses are not participants in “spectacle or escape, or passive avoidance, it is the deadly game of living with loss, living despite the humiliation of trying endlessly, living despite failure.” [13] Works Cited

[1] “The NCTR Supports Honorary Witness and invites Minister for further Education,” The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. July 16 2021. https://nctr.ca/the-nctr-supports-honorary-witness-and-invites-minister-for-further-education/ [2] Schiller, Friedrich. The Works of Friedrich Schiller: Early Dramas and Romances...translated from the German. George Bell & Sons, 1881, p xiii. [3] Nock, Samantha. “Being a witness: The importance of protecting Indigenous women's stories,” Rabble. September 5 2014 https://rabble.ca/blogs/bloggers/samantha-nock/2014/09/being-witness-importance-protecting-indigenous-womens-stories [4] Nock, “Being a witness.” [5] Salverson, Julie and Bill Penner. “Loopings of Love and Rage: Sitting in the Trouble,” Canadian Theatre Review 181, (Winter 2020): 37. doi:10.3138/ctr.181.006. [6] Salverson, Julie. “Taking liberties: a theatre class of foolish witnesses,” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, (June 2008): 246. [7] Salverson, “Taking liberties,” 246. [8] Salverson, “Taking liberties,” 247. [9] Salverson, “Taking liberties,” 248. [10] “About Trophy,” https://www.thisistrophy.com/about. [11] “About Trophy,” https://www.thisistrophy.com/about. [12] “About Trophy,” https://www.thisistrophy.com/about. [13] Salverson, “Taking liberties,” 253. Participation assumes an invitation. Something is happening someplace and audience-players are welcomed with an invitation into the territory of the magic circle of play. But what if we are not welcome? What if some are welcome participants but others are not? Normally, the value of universal access is invariably taken as given, and yet, there are some contexts where a closed door is not only a valid option, but is itself a powerful dramaturgical strategy that speaks in meaningful ways to the nature of an invitation and what or who authorizes that border crossing. One specific example of being unwelcome manifests in David Garneau’s articulation of the necessity for what he calls “irreconcilable spaces of Aboriginality.” [1] These are “gatherings, ceremony, nehiyawak (Cree)-only discussions, kitchen-table conversations, email exchanges, et cetera, in which Blackfootness, Metisness, and so on, are performed without settler attendance. It is not a show for others.” [2] The unwelcome of these irreconcilable spaces first assert a private space, convenings---physical or virtual---that are closed to the gaze of outsiders. These are spaces of non-visibility that resist scopophilia. Second, Garneau says that beyond resistance to looking, these spaces also operate in resistance to resource extraction. There is a need to evade and resist colonial modes of engagement which are “characterized not only by scopophilia, a drive to look, but also by an urge to penetrate, to traverse, to know, to translate, to own and exploit. The attitude assumes that everything should be accessible to those with the means and will to access them; everything is ultimately comprehensible, a potential commodity, resource, or salvage.” [3] [What does this mean for my own Western-trained academic praxis? Read, collect, quote, cite, analyse, apply, synthesize, extend to new contexts. This is what I do. I have become acutely aware that it is without doubt a deeply extractivist approach. I begin with the assumption that everything is available to be read, quoted, and repurposed. Looking at this page, quotation marks and parenthetical citation brackets now look to me like nothing so much as spoons for my hungry scholarship and the scoop-like jaws of a giant yellow bucket excavator. I feel ashamed of my familiar mode of operation, and at the same time am profoundly uncertain how to proceed. How to engage with knowledge from other sources with respect and reciprocity?] Dylan Robinson in his book Hungry Listening takes the next logical step: “If Indigenous knowledge and culture is mined and extracted, then it would follow that another key intervention for disrupting the flow of extraction and consumption would be the blockade. [4] He then does exactly this and performs the exclusionary blockade surrounding an autonomous textual territory. On page 25 of the Introduction, he writes, “I ask you to affirm Indigenous sovereignty with the following injunction: If you are a non-Indigenous, settler, ally, or xwelitem reader, I ask that you stop reading at the end of this page. . . . The next section of the book, however, is written exclusively for Indigenous readers.” [5] He also provides an explicit invitation to rejoin the book later at the beginning of Chapter 1. Among the modes of non-participation in participatory theatre, the strategy of the blockade, of being unwelcome, functions differently than other multilinear mappings that also close off possible paths. In a choose your own adventure experience, multiple paths are available to you, but standing at the juncture point you choose one over the others. You still remain ignorant; it is an experience that you will not have, but the key difference is that you had an open choice. And that awareness of the path not chosen, like the blockade, functions to create dramaturgical meaning. The form of the experience can be marshalled to speak. The path that is closed off not by choice but by the consequences of my action is also distinct from the blockade. In Love Without Late Fees, an escape room/theatre play by Outside The March, for example, if our group of audience-players ‘wins’ at our episodic task then the plot moves in one direction and the couple rent one movie, but if we fail at the task, they rent a different movie and the romance plot moves in a different direction. Again there is a path that is removed from our experience but the closing of that option is causal, tied directly to my actions; there are transparent consequences. In both cases, the closed path could have been traversed within the parameters of the game-play. Any of the paths would be equally viable under other circumstances without prejudice. What did I do at Robinson’s injunction point? I stopped reading. My personal history is one that renders me unwelcome in this delimited space. I am the child of refugees. My parents arrived as children on Turtle Island to the city of Montreal by ship across the Atlantic in the years following World War II. All four of my grandparents were Holocaust survivors; their parents, most of their siblings, nieces and nephews having been murdered by the Nazis. Being stateless, Canada was a welcome haven. Clearly, I have no rights of welcome to asserted territory of Indigenous sovereignty, geographical or textual. However, my lifelong citizenship story is founded on the imaginary of being welcomed as a proud first-generation Canadian, and so it is a new thought for me to stop and think about who did that welcoming all those decades ago and what was their authority to do so? This is one of the effects of Robinson’s performed blockade. What does it feel like to be locked out? Surprise, certainly. What? I’m blocked?! That first hard stop is followed by a tingling pull of curiosity and FOMO. What am I missing? No peeking. Really, no peeking. I feel like an outsider. This is of course the intention and I must admit that this is not a common feeling for me. I am pretty accustomed to being able to go where I want and feel welcome. I feel a bit bruised. Hmmph. Ultimately, my feeling is respect for the closed door; it is rude to go somewhere and force your way in when you are explicitly asked not to attend. But, this is exactly what I have done in life. (Even if not me, myself, directly as an immigrant, at the minimum I am the mute beneficiary of my unwitting ancestors’ door crashing.) And so the performance in Hungry Listening of a participatory blockade not only opens consideration of my personal imbrication in colonization, and challenges me to figure out why I am unwelcome and what I can do in response, but on a general level engages the flip side of thinking about the invitation. Instead of focusing on how to make the transition to theatrical participation easy as Gareth White does, [6] by rendering that transition very difficult if not impossible as Robinson does, we now may be engaged with how and why the border crossing of participation sometimes should be hard. [7] Who are the rightful holders of sovereign authority inside the circle, and what are the appropriate credentials to enter? [1] Garneau, David., “Imaginary Spaces of Conciliation and Reconciliation: Art, Curation and Healing.” Acts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action In and Beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Edited by Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin. Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2016, 27.

[2] Garneau 27. [3] Garneau 23. [4] Robinson, Dylan. Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies. U of Minnesota P, 2020, p.23. [5] Robinson 25. [6] White, Gareth. Audience Participation in Theatre: The Aesthetics of the Invitation. Palgrave Macmillan 2013. [7] To date, I have not yet encountered this kind of unwelcome of an audience in an actual theatrical performance; however there are some recent adjacent examples relating to theatre-making processes and also to theatre reviewing. In the rehearsal process for Encounters At The Edge of the Woods (Hart House Theatre, September 2019), director Jill Carter held some separate sessions for Indigenous and non-Indigenous cast members. Moyan, Trina. “Encounters at the Edge of the Woods: Answering Calls and Standing at the Edge of a Pandemic.” Canadian Theatre Review 184 (Fall 2020): 76-81. When Yolanda Bonnell’s play bug was presented by Theatre Passe Muraille in February 2020, Bonnell asked that the work be reviewed only by folks who are Indigenous, Black, or people of colour. One of Bonnell’s asserted reasons is “that bug is an artistic ceremony, which she says ‘does not align with colonial reviewing practices.’” Fricker, Karen. “Critics who aren’t Indigenous, Black or people of colour aren’t invited to ‘bug.’ Yolanda Bonnell explains why.” Toronto Star 10 February 2020. https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/stage/2020/02/10/critics-who-arent-indigenous-black-or-people-of-colour-arent-invited-to-bug-yolanda-bonnell-explains-why.html. Recollet, Karen and J. Kelly Nestruck. “A Cree professor and a white critic went to Yolanda Bonnell’s bug. Then, they discussed.” The Globe and Mail 16 February 2020. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/theatre-and-performance/article-a-cree-professor-and-a-white-critic-went-to-yolanda-bonnells-bug/ See also: Carter, Jill. “A Moment of Reckoning, an Activation of Refusal, a Project of Re-Worlding.” Canadian Theatre Review 186 (Spring 2021): 8-12. https://ctr.utpjournals.press/doi/full/10.3138/ctr.186.002; Carter, Jill. “My! What Big Teeth You Have!” On the Art of Being Seen and Not Eaten.” Canadian Theatre Review 182 (Spring 2020): 16-21. Remixed, created by the artists behind Trophy [1], blends the materiality of receiving a gift in the mail with an app-based personal questionnaire. As “a listening party for one, performed together across time and space in a collective experience,” the artists invite interactive participation before, during, and extending beyond the scope of the time we share together at the show. The creators, Laurel Green, Sarah Conn and Allison O’Connor are experts in care, moving audiences softly through a personal playlist of stories and music while offering us tools to literally plant change and watch it grow. Nurturing change through emergent strategy is the name of the game in Remixed. Our small acts assemble the show but also re-assemble ourselves, sending us off into the world with a sense of our own potential. And a seed. When the show starts, I am invited to open a cardboard box that arrived by post a week prior. Inside the box, there is a small cardboard pot, a soil pellet, a beautiful hand crafted paper ball, and a circular piece of cream canvas mat with three painted circles on it, delineating where to place the other objects you were gifted. After placing the items on the cloth as instructed, I am then invited to fashion the cardboard box into an upright phone stand set for the performance. (Genius!) After “setting the stage” for myself, I answer a series of meaningful and personal questions. Through the interactive app, I select a graphic of a face or a visual of a heart beat to communicate how I’m feeling at the time of performance. The app asks questions about what things make me calm, the music I listened to as a kid, the music I listen to now, and my relationship to change. As I ponder my own intense relationship to systemic change in light of these questions, I meet the spinning wheel, showing me that something new is aggregating. The app then spits out a custom playlist, specifically made for me. Featuring a collection of both music and personal monologues inspired by my answers to the preceding questionnaire, this playlist is to be listened to while I move through the other instructions from the show. The first song that preceded the monologues was totally on point with my assertion earlier that I definitely listened to early 2000s pop when I was younger; Gwen Stefani’s “Hollaback Girl” blasts through my headphones. I felt seen, I felt heard, I want to dance along. The playlist was a gift, personally made for me, that put my lived experiences and memory in conversation with an emergent world beyond (See I LOVE YOU.). Listening to music from my youth while listening to stories about radical change from people I’ve never met put the personal in conversation with the political. My curated stories were mainly autobiographical stories of participation in systems change. I heard from a queer person who told the story of the first time they participated in a Pride parade. I heard from a Sri Lankan immigrant who runs programs to demystify the process of getting permanent residency in Canada. I heard from someone who runs cultural sensitivity training. I heard from an Indigenous woman who told the story of the healing ceremony that happens when a family member dies. While I listen to this playlist of songs and stories, I am told to place the soil pellet in the pot and fill it up with water. I take apart the little paper ball to find it full of seeds. Then I plant the seed in the soil. I am left with the explicit instruction to continue to nurture the plant, to keep it alive. I am challenged to carry the stories of individual and systemic change I have heard with me beyond this moment, to actively encourage visible and emergent change through the now embodied metaphor of nurturing a little sprout. The key point here is that this gift stays with me. Jenn reminds me that we don’t usually get mementos like this in bourgeois theatre. My sprout grew on my windowsill for a month after the show. Each of the stories in my personal playlist swirled around tiny individual intensely-local moments of change inside a bigger systemic movement. The stories lean into what adrienne maree brown calls emergent ways of thinking around the "the way complex systems and patterns arise out of a multiplicity of relatively simple interactions.” [2] Remixed offered me not only autobiographical stories of small participation in big change and but also an invitation to try it out myself. This kind of emergence, specifically planting the seed, is a future-oriented phenomenon. The seed proves a perfect metaphor for the fact that small acts of nurturing and care do the real work to change the world by first changing my world. The website for Remixed cites Octavia Butler to remind us that “all that you touch you change, all that you change, changes you.” We hear the stories of change, they change us, we actively bring life to something green. Although the modest scale of Remixed prevents us from accessing fully emergent pattern-making, the artists echo Augusto Boal’s rallying cry that performance can act as “rehearsal for the revolution.” [2] Remixed is an example of training for phase change, or what Jenn calls “proto-emergence.” This is how we start with just one of those simple interactions brown describes. The first in a potentially rich network of such interactions. Through planting the seed, I was acting as a vehicle for change --from the storytellers, through my hands, into the dirt, up into the sun. [1] Trophy is an award-winning interdisciplinary creative collective based in Ottawa that makes both performances and installations. Besides Remixed, they are known for their installation Trophy, a series of tents that house personal and autobiographical stories of change.

[2] adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy : Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico: AK Press, 2017, pg 2. [3] Augusto Boal, Theatre of the Oppressed. Theatre Communications Group, 1985, pg 155.

Rebecca Draisey-Collishaw and Kip Pegley

It’s been more than a year since we heard news of the novel coronavirus, now ubiquitously recognized as Covid-19. And just over a year since much of the world found themselves with some version of a stay-at-home order. Since the beginning of 2021, the news has been full of anniversary reminders of the profound moments that have drastically altered the ways that we live and our capacities to interact. Indeed, it seems likely that one-year memorials will thematize our experiences in 2021. While many of our remembrances are woven with grief, anger, loss, and loneliness, with April 7 upon us it’s perhaps worth recalling the anniversary of a gaff-turned-sensation that brought laughter, inspired dialogue, and built community solidarity. In this blog post, we’ll explore how the DIY aesthetics and the figure of the prosumer (audiences that actively and interchangeably consume and produce content) muddy the waters between content creators and audiences and necessitate a revisioning of what it means to participate in the public life of a nation.

During the first 110 days of the Covid-19 pandemic in Canada, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau provided almost daily updates from the steps of his home (learn more about Trudeau’s almost-daily Covid-19 updates at https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/110-days-81-addresses-to-the-nation-what-pm-trudeau-s-covid-19-messaging-reveals-1.5019550). On April 7, while describing measures each of us should take to hinder the spread of the virus, he uttered the now-infamous—and infinitely cringe-worthy—advice that we should avoid “speaking moistly” on each other. Trudeau’s original announcement had a massive audience: CBC’s English language services, for example, reported an average reach of 4.4 million television viewers and 1.9 million radio listeners for the PM’s morning updates during this period of the pandemic. And those numbers only include people who tuned in via CBC; the actual audience more than doubles when other broadcasters and coverage in both official languages are considered (https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/grenier-pm-press-conferences-1.5587214). It was a verbal gaff with legs of its own that evoked laughter from audiences, comment from pundits, and elaboration by artists. Indeed, one of those artists gave Trudeau’s utterance wings when he transformed the speech into a music video with danceable beats. On April 8, 2020, Brock Tyler (known by the username anonymotif) released his version of “Speaking Moistly” on YouTube. It was a runaway success that defied his expectations and went viral overnight. Tyler’s version of Trudeau’s speech takes the form of a “meme song,” a composition that involves creatively combining and remixing memorable video and audio, usually with the purpose of offering commentary on a person, moment, or concept. Meme songs exist and circulate exclusively via social media. Tyler's “Speaking Moistly” uses techniques like zoom, delay, slow motion, and quick cuts from the news footage of the PMs address to splice together a music video that follows the simple song structure. The song itself is an autotuned manipulation of Trudeau’s speech, which is underlaid with electronic effects, drums, and synthesized harmonies.

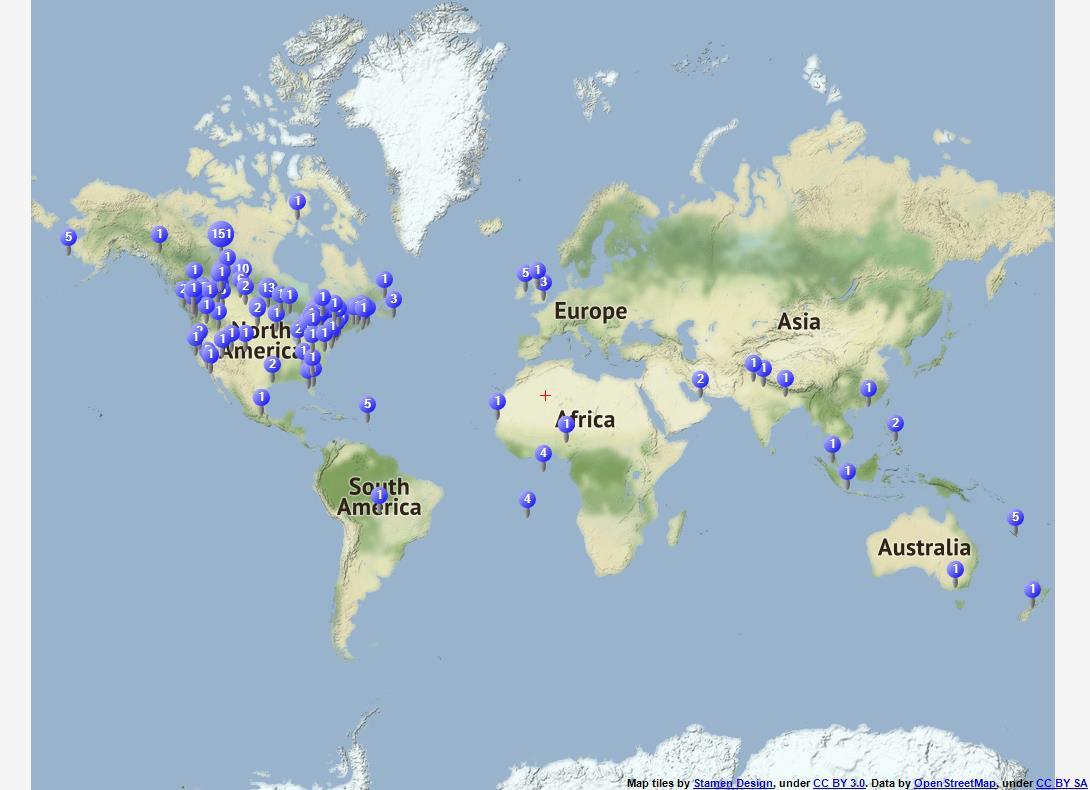

Within 24 hours, the music video received more than a million views. And a map of 1,393 Twitter tweets that appeared between April 18 and April 28, 2020 and featured #SpeakingMoistly shows that by the end of the month the song had been shared throughout much of the world.

The viral popularity of “Speaking Moistly” on social media was covered in traditional media, with the result that Trudeau’s words effectively hung around in the media cycle longer than could otherwise be expected, reaching an ever-expanding audience and building a shared rhetorical vision centred on Trudeau’s pandemic management. This rhetorical vision could then be maintained, elaborated, and contested through the participation of prosumers in digital spaces. As Tyler later reflected:

I think that the statement itself had enough behind it in terms of comedy that we probably would have seen a fair bit of that […] in terms of the slogan living on t-shirts. But I think the song just made it kind of hang around in people’s consciousness a bit longer. (interview with author, 23 September 2020) In other words, what Tyler’s meme did was promote spreadability via social media platforms (like YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, etc.) and, after initial successes, via a licensed audio-only version of the song to Spotify and iTunes. The relationship between audiences, memes, and Web 2.0 technologies is at the heart of that spreadability—and the meanings that emerge as messages traverse across off- and online spaces. A phenomenon of social media, meme songs complicate how we think about traditional roles of creator, performer, and audience. Social media is a form of participatory culture that erases distinctions between (active) producers and (passive) consumers, instead relying on the figure of the prosumer (producer + consumer) to both create and engage circulated content. In the case of “Speaking Moistly,” Trudeau may have authored a memorable phrase, but his image and words quickly transformed to source material for creative elaboration by others. Tyler was a pivot between on- and offline spaces, and the embodiment of the prosumer: he was an audience for Trudeau’s speech, creator of an artistic/parodic meditation on a “very Canadian” moment, and, ultimately, a source of material for subsequent elaborations by other prosumers. Legitimizing mainstream politics

At first glance, Tyler’s meme comes across as a parodic public service announcement (PSA)—and much needed moment of levity in a period of crisis. It was comedy with a familiar feel for many Canadians. After all, political parody has a long history in Canada.

Parody is a form of humour that exaggerates the familiar aspects of an original text by, for example, caricaturing a person’s looks or comments, all without judgement (cf. Young 2014). This form of political humour is common fare in a plethora of CBC comedy shows (ranging from somewhat to heavily political) that have aired over the decades. These include, among many others:

Scholars of comedy describe parody’s function in rallying public opinion and humanizing political figures (e.g., Jones 2009: 44). Memes can fulfill a similar purpose, but their user-generated origins validate an “official” message in a cultural context that increasingly doubts the veracity of politicians and experts (cf. Parlett 2013). Youtuber comments about “Speaking Moistly” seem to support the capacity for parody to rally public opinion, humanize, and affirm Trudeau’s pandemic management efforts. As one person commented, “I love it. Trudeau has a good sense of humour he saw it and laughed too. So cute.” Another viewer added, “Love him more than ever!” A more critical voice (who identifies as proudly Conservative) tweeted, “And yet still Trudeau can't speak English. But let's cut him some slack #speakingmoistly takes great lip dexterity.” While unintentional, “Speaking Moistly” may have helped mitigate partisan divides during the strictest period of pandemic restrictions (to date) in Canada. Producer vs/and consumer

There’s a necessary distinction that must be drawn between the parodies produced in the official contexts of the CBC and the user-generated memes that circulate over social media. Comedies like Royal Canadian Air Farce or 22 Minutes might contain skits—or even music videos—that are markedly like “Speaking Moistly” in their approach to poking fun at politicians. However, the assumptions about creators, audiences, and the direction of communication are quite distinct, even irreconcilable.

Audiences for shows like the Rick Mercer Report, for example, are expected to passively consume content (and hopefully be informed about important issues). Information, in other words, flows from creator to audience. The participatory culture that is the norm in social media spaces, however, presumes that audiences are also creators—that consumption begets new content and popularity involves more than a high rate of views. That is, the flow of information is multidirectional, with almost limitless potential for engaging and reinterpreting source content. Reacting to the popularity of “Speaking Moistly,” Tyler explained: When I was working on it, I really had no expectations at all. And to see it sort of slowly build momentum and then […] it just sort of takes off and it's out of your control now and you see the sharing happening in real time and it's sort of like this avalanche of social media activity and it's addictive at first because it's so fun to see people enjoy something you made. […] I think what was neatest about it, and one thing I certainly didn't expect [was] for people to do covers of it. […] I had to keep the song really simple because I was doing it so quickly. And I really didn't think through how I was going to do it. I basically went with every first idea I had. And it ended up being a song that was simple enough, melodically and chord wise, that people could cover it. And so to see that first cover come out, which was […] an acoustic cover and there were a few that kind of came out at the same time, like ‘oh that's so cool.’ I just had no expectation that people would want to embody the song and make their own version of it. (interview with author, 23 September 2020) Tyler went on to explain that when he creates meme songs he is concerned with the fidelity of his representation; he’s interested in highlighting the humour of the moment, but he doesn’t want to put words into anyone’s mouth by splicing and reordering original statements (interview with author, 23 September 2020). And yet, consider Tyler’s words: “it just sort of takes off and it’s out of your control.” The meme, the image, the music, and the message have the capacity to move, reinforce, and reinvent meaning almost infinitely. Politics in an age of controllessness

Politics and communications scholar Martin A. Parlett asserts that:

Online activism in vacuo is nugatory—the flame of social media revolutions is sustained by the oxygen of offline action and cultural participation. Presidential politics is still governed by votes counted at the ballot box and not the number of blog posts or retweets in a candidate’s favor. Broadcast still plays an important role in consciousness shaping, just as the doorstep or back fence persist as the more important sites of political persuasion. (2013: 134-5) Writing on the role of social media during the 2008 presidential campaign in the United States, Parlett further contends that “participatory culture is Janus-faced” (2013:152) and that Barack Obama’s successes in this domain emerged, in part, from an appreciation of the “controllessness” social media engagements. While Obama successfully mobilized his base through Web 2.0 technologies according to a positive shared rhetorical vision, the opposition created a countervision that was just as powerful. That is, for each message Obama released into the world, each online engagement contained the potential to be read and recirculated as confirmation of an oppositional worldview. For Parlett, online activism only becomes politically effective when it begets offline engagements, with prosumers fluidly moving between domains of engagement and fueling opportunities for further participation. “Speaking Moistly” is illustrative of an online engagement with offline consequences: the viral popularity of Tyler’s meme on social media meant that millions of viewers received well-informed public health advice that helped rally the population in a period of crisis. But as Tyler himself points out, audiences didn’t just watch, share, and comment on “Speaking Moistly.” Like Tyler, they were prosumers who participated in making meaning by using his meme as a source for their own shareable creations. The resulting profusion of Tiktoks, YouTube videos, Instagram shares, and Tweets is so vast as to defy categorization. They include:

There is a tendency to focus on social media as a source of disinformation and the embodiment of the worst qualities of humanity. We all have a responsibility to engage critically with the content that circulates through our various feeds. But focusing only on the capacity of Web 2.0 platforms to circulate fake news or radicalize individuals to anti-social ideologies perhaps gets in the way of appreciating what the controllessness of this medium means, and how we might leverage the performative opportunities that emerge when the lines between creators and audiences blur beyond distinction.

Rebecca Draisey-Collishaw completed her PhD in ethnomusicology at Memorial University in 2017 and held a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Dan School of Drama and Music, Queen’s University from 2019 to 2020. Rebecca co-edited the Yearbook for Traditional Music (2018) and curated the Irish Traditional Music Archive's digital archival exhibition, A Grand Time: The Songs, Music & Dance of Newfoundland's Cape Shore (itma.ie/newfoundland). Her research, which focuses on intercultural musicking and public service broadcasting in multicultural contexts, appears in MUSICultures (2012), Ethnomusicology Forum (2018), Contemporary Musical Expressions in Canada (MQUP, 2019), and Music & Politics (2021).

Kip Pegley is a Professor in the Dan School of Drama and Music, Queen’s University and a researcher with the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research. Pegley is the co-editor of Music, Politics and Violence (Wesleyan University Press, 2012), and, more recently, their work on sound and trauma has appeared in Singing Death: Reflections on Music and Mortality (Routledge, 2017), Music and War in the United States(Routledge, 2019), and MUSICultures (2019). Sources Patricia Cormack and James F. Cosgrave. 2013. Desiring Canada: CBC Contests, Hockey Violence and Other Stately Pleasures. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Jeffrey Jones. 2009. “With all Due Respect.” In Satire TV, ed. Jonathan Gray, Jeffrey Jones and Ethan Thompson. New York: New York UP. Martin A. Parlett. 2013. “Barack Obama, the American Uprising and Politics 2.0.” In Social Media Go to War: Rage, Rebellion and Revolution in the Age of Twitter, ed. Ralph D. Berenger, 133-167. Spokane, Wash: Marquette Books. Dannagal G. Young. 2014. “Theories and Effects of Political Humor: Discounting Cues, Gateways, and the Impact of Incongruities.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication, ed. Kate Kenski and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. https://www-oxfordhandbooks-com.proxy.queensu.ca/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199793471.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199793471-e-29?rskey=haFjSw&result=1 It is reminiscent of a joke told by a 6-year old. But instead of “How is an elephant like a loaf of bread?”, I’m asking, “How is QAnon like Ratatouille: The Musical?” In addition to their shared context, both phenomena rising to mass consciousness in the late days of the Trump presidency and in the shadow of pre-vaccine pandemic lockdowns, both QAnon and Ratatouille: The Musical are both manifestations of participatory and emergent behaviours, made possible by web 2.0 collaborative interactivity. But whereas, the amateur artists of Ratatouille: The Musical created, well, a musical; the adherents of Q who elaborate the intricacies of the QAnon orthodoxy created an entire alternate reality. QAnon is an apparently widespread American conspiracy theory, born in the dark corners of the web, that believes among other things, that Donald Trump has been chosen to save America from a deep state cabal of Satan-worshipping Democrats, who are also pedophiles. [1] Ratatouille: The Musical, on the other hand, was born on TikTok, and is an assemblage of lyrics, music, dialogue, choreography, set and costume design sketches, that re-imagine the animated Disney/Pixar movie Ratatouille as a Broadway-style musical. [2] In early January 2021, both QAnon and Ratatouille: The Musical seeped out of the virtual realm and into reality. Over the weekend of 1-3 January, a production featuring a cast of well-known Broadway performers, streamed on Today’s Tix. The event raised $1.9 million for the Actors Fund. [3] On 6 January, the day of the certification of the results of the 2020 election, a crowd comprised of right-wing ‘militias’ and QAnon supporters who believed that the election was ‘stolen,’ stormed the US Capitol building with the aim of disrupting those proceedings. Five people including Capitol police and protestors died. [4]  Ratatouille: The Musical is at its heart a crowdsourced work. Beginning with an a cappella rendition of an ode to the main character Remy the rat, posted by TikTok user Em Jaccs, other TikTok denizens augmented this initial song, Daniel Mertzlufft added orchestral scoring. Others constructed a set model, wrote and performed more songs, invented choreography, even puppets. Not only is it participatory, but the iterative recycling and re-imagining marks this as a potentially emergent phenomenon. There is no director, no producer, no playwright or composer. Apart from the inspiration of the original movie, there is no controlling animus at all. There is no gatekeeping. Every contribution is valid—even potentially contradictory or exclusive elements become enfolded into the sprawling motley whole. One notable characteristic that distinguishes the Ratatouille project from myriad other similar collective works is that there is a knowing wink, a sly pretense that this could in fact be, IS in fact, real. Rebecca Alter makes this observation in her history of the musical’s development on Vulture.com. She writes, “the specific appeal of the Ratatouille musical is the alternate reality of it all: It is not inconceivable that there is a timeline where Ratatouille: The Musical was announced as a big-budget, family-friendly production alongside the likes of Aladdin, The Lion King, and The Little Mermaid.” [5] Additional creative elements that project that reality include a (faux) Broadway-style yellow-header Playbill and video from a high school cast party at Denny’s. This is where Ratatouille: The Musical tips into performance--using mimetic representation to create (probably) alternate fictional worlds. Pervasive games, or alternative reality games (ARG) invite players to participate in covert activities in a hidden universe existing in parallel with the usual mundane one. One of the simplest pervasive games is perhaps Assassins where a group of friends or co-workers are each given the name of another person in the group to “kill.” The kill, depending on the agreed rules, is accomplished with coloured dot stickers, water pistol, or simple touch tag. If you successfully assassinate your target, you take the name of their target and move on to your next mission. The winner is the last person still alive. The pervasive nature of Assassins arises from the extended duration and expansive boundaries of the game that takes place in the interstices of everyday life over the course of days or even weeks. There is also a critical element of being secret weirdos, as your kills cannot be witnessed by anyone else, especially non-participant bystanders. The foundational book on this subject is Pervasive Games: Theory and Design [6] by Markus Montola, Jaakko Stenros, and Annika Waern. They begin with Assassins and trace the proliferation of the genre through fictional-game-events like The Beast, [7] Shelby Logan’s Run, [8] and Uncle Roy All Around You, [9] linking at the end to the global TV phenomenon of The Amazing Race. These game-performance hybrids necessitate the imaginative invention of a separate world for the in-group of players within the magic circle. By this logic, QAnon is a massive pervasive game. With its focus on discovering and decoding secret messages, the active logic of QAnon’s search for the ultimate truth is the same. In a September 2020 article in WIRED Magazine, writer Clive Thompson documents the insights of game designer Adrian Hon, who makes exactly this observation: “ARGs are designed to be clue-cracking, multiplatform scavenger hunts. . . .To belong to the QAnon pack is to be part of a massive crowdsourcing project that sees itself cracking a mystery.” [10] There is real pleasure in solving these perceived puzzles.[11] The distinction however between the QAnon alt-reality narrative and that of something like The Beast is that in the case of The Beast, it is the fictional creation of Microsoft/Warner Bros to support the promotion of the film AI: Artificial Intelligence. There is an intelligence behind the game scenario. For QAnon, the hidden narrative that they seek to reveal is non-existent. There is no secret plan for global domination. There is no wizard behind the curtain. The truth is not out there. (Really.) Rather the ‘truth’ is being created iteratively by the seekers out of nothing. What’s fascinating about this, then, is how this is an illustration of emergence in action. Emergence is a participatory phenomenon. Emergence doesn’t need a leader or a coherent narrative to get started, coherence arrives as a dumb product of the game mechanic, of the controlling algorithm. It is Internet-based social media platforms that provide the accelerator. Emergence algorithms require thousands, if not millions, of reactive local responses. Think flocking birds or colony building ants. Conspiracy theories are not in and of themselves participatory. They are the result, however, of a participatory emergent algorithm that produces the standard genre characteristics of a conspiracy theory (or a murmuration of starlings or insect architecture). BONUS THOUGHT: Participation in conspiracy theories seems to align with feelings of powerlessness, perceptions of lack of control. It is not coincidental that paranoid conspiracy narratives tend to foster themes of control by elite “others.” (Sometimes radical socialist Democrats and Zionist globalist Jews, but also aliens). Mariah points out quite rightly that the musical theatre creators of Ratatouille: The Musical are also, within the realm of professional Broadway-bound musical development, powerless. Their pretense that their Ratatouille musical is real is a gesture of defiance that recognizes their outsider status. [1] Roose, Kevin. “What is QAnon, the Viral Pro-Trump Conspiracy Theory?” New York Times. 4 February 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/article/what-is-qanon.html