|

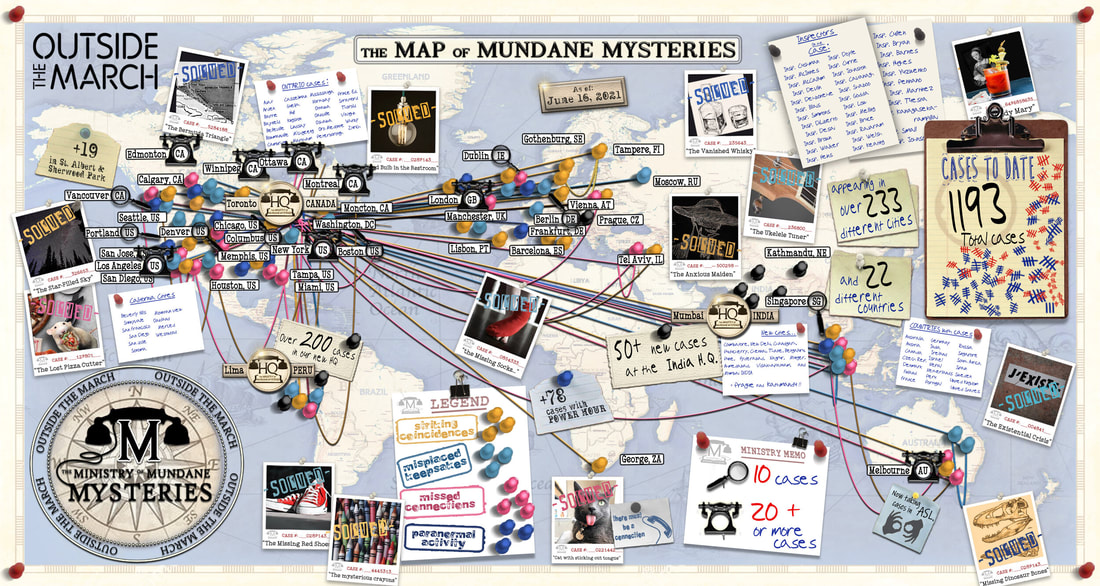

#ThrowBackThursday. This post looks back to a play that we saw and wrote about back in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although this show analysis speaks to a performance I attended in 2020, the Ministry of Mundane Mysteries continues to this day in February 2022! After two successful runs, “solving over 1000 cases in 233 cities worldwide,” the Ministry of Mundane Mysteries now runs their shows on-call, with a team of 25 actors available for booking anytime. You can register for this show here. My mystery was “The Case of the Missing Cake Pan.” Launched in March 2020, The Ministry of Mundane Mysteries is a performance series imagined by Toronto-based company Outside the March to “spark connections through Telephonic Investigation.”[1] In this live, episodic, performance for one, participants are treated to a tailor-made interactive play. Starring the participant, it’s a whodunit that unfolds over the phone. The rundown. Each participant is responsible for thinking up their own mundane mystery. The door that won’t close? Radioactive running shoes? Unripening avocado? No missing socks though, “we’re socked out over here,” as Commissioner Mallory Murtaugh says in the FAQ on the Outside the March website. For six days in a row, at the same time each day, your mundane mystery comes alive through a zany cast of characters that draw you into conversation as you co-construct a personalized adventure. Throughout this adventure, nuggets from the participant are weaved into a structure predetermined by Outside the March. This “fill in the blanks” style of performance, classified by Espen J. Aarseth as using a “configurative” user function, [2] relies on participants to insert responses to a recipe crafted by the artist. Similar to mad libs, the pleasure comes from a low-stakes participatory input into the work. To accommodate the bespoke nature of each mystery, the plays follow a strict dramaturgical pattern that is common to every episode while leaving room for the insertion of unique autobiographical details. Developing an improvisational collaborative dramaturgy, Outside the March explores the balance between structure with flexibility. How big are the spaces I am filling? Will how I fill in my blanks change the direction of the piece? Mundane Mysteries is built as an ordered series of checkpoints and pivotal moments that became identifiable to us as we compared our personal mysteries. Phone Call 1: “The Interview.” The first call is from an Inspector from the Ministry, who is handling your case. Inspector Johnson interviewed me about my mystery, pressing for the names of any suspects or leads I wanted them to follow up on. Did I suspect my roommate? Then, you are asked a list of seemingly random questions. Where do I buy coffee? How long have I lived where I live? Because this first contact is framed as an intake interview, the imposition seems natural. They are leaving no stone unturned! My Inspector is trustworthy, thorough and insists she will do all in her power to solve this case. The phone call ends with the Inspector letting you know they will be in touch. Phone Call 2: “The Informant.” The second phone call comes from a different voice. They call in a whispered panic. “I shouldn’t be talking to you. Don’t tell anyone.” In my case, the caller was an Australian man who used to work for Northside, my favourite local coffee shop. Clearly, he had done his research weaving in details about the Kingston coffee scene, the coffee shop, the Northside menu, and the women who run it. He then divulged that he believes they are behind this missing cake pan. This was my first lead. Phone Call 3: “The Threat.” The third phone call comes from another new voice. At first, the caller purports to be a representative of a reputable business (Loblaws supermarket, in my case). They offer an easy solution to your mystery and invite you to close the case. “You don’t need a cake pan, anyway. You can buy your cakes from us.” As the phone call devolves, you learn they are not who they said they were and instead they work for the folks accused in the last phone call. My caller confessed to actually being a lawyer for Northside and threatened me with a rogue boomerang if I didn’t retract my accusations and call off the investigation . . . or else. Phone Call 4: “The Stakeout.” In the fourth call, your Inspector finally returns, asking you for updates on the investigation or details on any weird phone calls you may have received. When you update them on what the two previous callers have said, they are unsurprised because they are calling you right now from a dangerous undercover situation investigating this very accusation. Whispering and afraid, my Inspector informs me that she is calling me from a hiding spot in the basement of Northside. She has ended up in a “boomerang room” (whatever that is). There is a loud commotion of percussive noise and yelling, and the call is promptly cut short. Phone Call 5: “The Decoy.” The next phone call serves to throw your nose off the trail. This caller offers a weird, out-of-left-field solution to your case and encourages you to close the investigation with the Ministry. In my case, this fifth caller was an optometrist (?!) asking if I had heard the recent rumour circulating about people who wear clear framed glasses (which I do, as I had previously told Inspector Johnston.) Apparently, folks all over the world in clear framed glasses have found themselves unable to see anything square. With hesitation, I said, “Yes let’s” [3] and the phone call ended with the caller shouting, “She bought it!” Phone Call 6: “Case Closed.” Finally, on the last day, you’ll hear back from your inspector, apologetic and embarrassed about the failed stakeout mission. They solve your case, thank you for your time, and play your favourite song to close the call. In my case, the folks had done some research about my roommate’s Mundane Mystery and blamed the case on her Inspector, Inspector Doyle. Apparently Inspector Doyle loves solving mysteries for us so much that he broke into our house, stole the cake pan in hopes that he would get to solve the case and look like a hero. Although he’s since been fired from the Ministry, they still can’t locate the cake pan. In a New York Times review of the Ministry of Mundane Mysteries, Alexis Soloski gave the show a rave review, insisting that the show “let me be who I am (a harried writer and home-schooling flop who might be drinking too much right now) and met me where I was, usually at my kitchen counter, slicing apples for the children’s lunch.” [4] Because this dramaturgical structure feeds into the drama and the well-recognized narrative of a “whodunit,” Outside the March inspired participants to assume agency through small pieces of autobiographical information and spun it into a wild adventure that made the listener feel “seen.” Soloski’s review captures that sense of personal care in an anxious time, The Ministry of Mundane Mysteries “asked about my world, listened and then let me slip free of it, at 10-minute intervals.” [5] Notes

[1] “The Ministry of Mundane Mysteries,” www.mundanemysteries.com. [2] Espen J. Aarseth, Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins UP, 1997), 64. [3] “Yes, let’s!” is a common technique used in improvisation drama games. One person proposes an activity: “Let’s squawk like chickens.” And the expected group reply is “Yes, let’s!” Followed by everyone commencing to squawk. The ethos of “Yes, let’s” is core to collaborative improv where any truth established by one person becomes so for all others. It is a willingness to accept any direction and to endorse it as the new reality. [4] Alexis Soloski, “There’s No Place Like Home (Theater),” New York Times. 16 April 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/16/theater/immersive-home-virus.html [5] Soloski, “There’s No Place Like Home (Theater).”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed