|

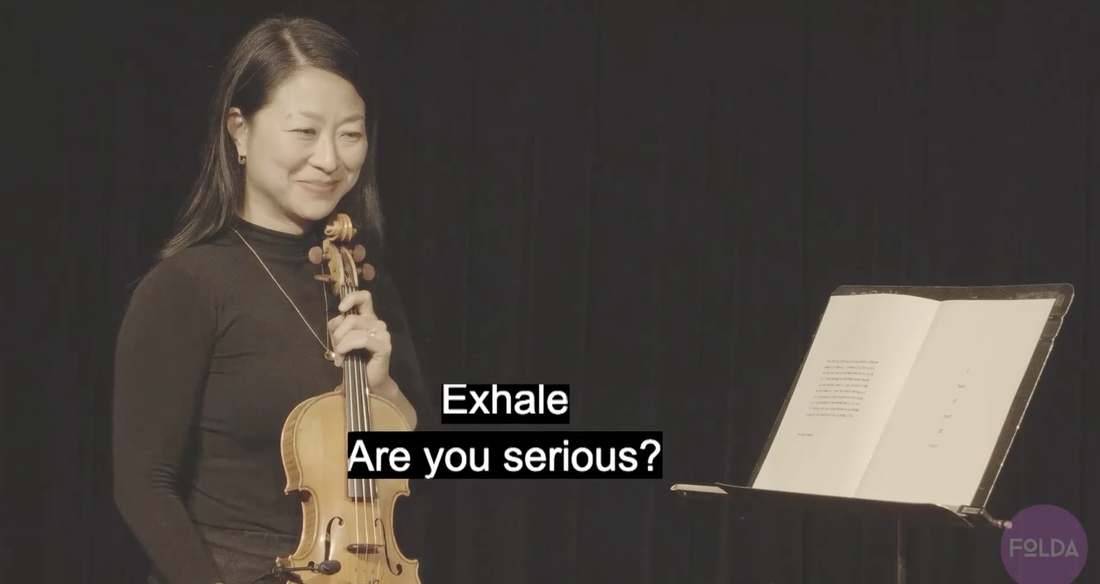

Mariah (Mo) Horner with Leslie Ting Mo: So I want to talk about your shows Speculation and What Brings You In specifically through the lens of participation. I thought we would maybe start with Speculation? I'm wondering if you could walk me through both what happened in the show and maybe explain a bit of your artistic process of arriving at the thought that participation was key to this work. Leslie: So the version that you saw of Speculation was the pandemic version which we staged online at FOLDA in 2021. Speculation was a theatrical concert with an immersive visual design based on the experience of vision loss. The show featured a monologue interweaved with live performances of Beethoven and John Cage to tell the story of my mother slowly losing her vision. In the online performance, everything up to the final participatory moment was pre-recorded and edited with experimental film. After the recorded concert we would go live in this final moment to collectively perform John Cage’s 4’33, a work entirely of “silence”. To participate, we encouraged audience members to phone into a phone number where I could hear everyone on the call and everyone could hear me and everyone else on the call. That connected conference call was then streamed online, which inevitably included feedback looping from all of the simultaneous phone-ins. There was a lot of balancing. We would ask people in the instructions to turn down their computer volume if they were also going to phone in so we could avoid the feedback that was gonna happen, but it was inevitable. Mo: I remember watching the show with a group of people. So we had to mute the laptop and put the phone on speaker. The risk for ambience feedback is high! Leslie: All you can do is sort of offer the instructions and then people are gonna do what they want, feedback was fine. That participatory element was very important to me when I was asked to pivot the show to online presentation. Speculation as it was was a theatrical concert that wasn't going to be captured well on camera, because of the way the lighting and video was designed. It was important to me that the online version still had this feeling of experiencing something together, with other people. Cage’s 4’33 is a heightened listening piece. All of Speculation is about listening, but when participants land in 4’33, I really wanted them to feel and hear each other’s lives. Listening is interactive. 4’33 is formalizing that idea of co-creating through listening. If life happens, life happens. If someone turns their livestream too loud, it’s fine. I think that while we tried hard to create the “silent” experience, because 4’33 is a silent piece, the piece is more about unintended sound and listening for that. There is an intent to be silent but you’re also really being open to sound at the same time. Mo: Oh, I love this! Leslie: I don't know if you remember but in our FOLDA performance, early in the phone call section someone said “Are you serious?” and it just started looping over and over again. We were laughing because that is such a perfect moment! I'm sure someone was caught off guard about listening and being heard. We were performing together in some ways, even more so than in the version where we would have all been together in a room pre-pandemic, because people made the choice to pick up the phone and join me. Mo: I want to talk about listening as a participatory activity because I know that you're also a musician! When we first started writing the book, we got into a major question around how typical traditional bourgeois sit-in-the-dark kind of theatre is also participatory, right? Interpreting, listening, watching, and considering are also participatory actions. Can you tell me more about why you think listening is participatory? Leslie: This was one of the biggest sort of realizations I had to make coming from the concert music world to the theatre world. In making Speculation, there was almost an immediate awareness that theatre audiences expected more. You can't just sit there and play the violin and think that's enough in theatre, most audiences need more lighting design, more characters, more narrative. Theatre audiences are leaning farther forward when they attend a show, they're waiting for you to take them somewhere. Music audiences are really used to being internal and they're not expecting the same kind of journey. The invitation for me in making Speculation was not necessarily to give you a narrative journey, but to invite theatre people to go inside and actively be with themselves. It’s like my experience with contemporary dance. Sometimes I feel like contemporary dance is hard for me to grapple with. I don't always know what is happening. But I would try to sort of understand it. I would try to internally meet it partway Mo: That makes sense to me! Music audiences are showing up to these experiences expecting to carry the interpretive labor, the participatory labour of “meeting it partway,” whereas traditional theatre audiences are sometimes less practiced in the labour of interpretation. This leads us to talking about your other show, What Brings You In. That show is also a softly participatory experimental music performance that explores the ways in which we engage with the therapeutic process and therapy is definitely participatory. Leslie: What Brings You In seeks an internal engagement and leaves space for multiple experiences . I know it’s alienating when you feel like you don’t “get it.” Learning the language of contemporary dance or new music can be alienating at first! I want to give my audience permission to just be with the sounds and I feel like sound is one of those things when you put it together with anything visual it competes, and so it’s the person sitting in the chair that decides where their attention goes. That’s also participatory. Mo: Let’s talk about one of your other major interests in making participatory work, accessibility. When you're staging something like What Brings You In, what are the implications of staging elements of the therapeutic process? What kind of things do you keep in mind as a creator? Leslie: In making What Brings You In, I realized that accessibility is complex. You’ve obviously got these government standards for things like public retail store websites around accessibility but the reality is, accessibility needs are nuanced and sometimes conflict with one another. In What Brings You In, I decided to instead focus on one set of access needs and go deep rather than do everything we can to offer shallow access needs across the board. As an audio-heavy piece, it was well suited for audience members with blindness and low vision. As you know, connection through interactivity is important to me so during What Brings You In, participants are welcome to move a cursor on their devices, like a calming doodle that was then projected on a screen. I worked with Marie Flanagan and Jess Watkin to balance care with the risk of overburdening people with too much explanation in the invitation. It took a lot of testing. We avoided text because it’s often inaccessible to folks without vision and we wanted sighted people to feel comfortable looking away from the screen and softening their vision to go more internal. Mo: Right! I remember when I saw What Brings You In, the staging decision to have you on the opposite side of the room to the screen was also a reminder that neither spot needed to hold my gaze for too long. I quickly realized that you were asking me to lie down and relax, receiving the information through my ears. This point that you're getting at around gaps and holes and giving the audience space, is connected to the earlier conversation that we had about experimental music. Offering the freedom to interpret and participate however is almost an access need? I feel like usually we think, at least in the context of participatory theatre, that access is mainly adding on top of the performance. Access is a supplemented thing. It's very interesting to hear you think about access as openness and emptiness, gaps and holes. Leslie: Yeah! Access as an additive thing is totally what seems to happen in theatre, and we tend to add it at the end. But it's more chaotic than building something with a specific set of access needs at the forefront. Mo: I once heard Calgary-based artist Jan Derbyshire say that in terms of access needs, “one size fits one.” Leslie: Exactly! This was a huge challenge for What Brings You In. In workshops, we kept getting recommended to add closed captioning but if you put words on a screen, that's all you're going to look at. If you're a sighted person or you have even partial sight, you're going to be drawn to that text. Or, for blind folks, screen readers will go off and distract you, we had to be ok with that. My interest with What Brings You In is to invite participants into this world of new music around self discovery and self understanding, through listening with others. The interactivity is important because I wanted the connective live experience still felt. There are still many gaps in the implementation and we want to give people the feeling of interacting and co-creating with plenty of space. Mo: The cursor reminded me of a classic fidget toy. I could see how it would help in listening. Leslie: I don't think we practice listening in general as a society. We're super good at watching and looking at details and having thoughts and feelings about what we see , but we're not as good with sound. Elinor Svoboda, one of the filmmakers for the pandemic version of Speculation who specializes and teaches sound in film, talked to me once about sound accessing the lizard part of the brain. I think hearing people are just not as practiced at interpreting sound like we do vision t.

Mo: Tanya Marquardt’s Some Must Watch While Some Must Sleep uses the distance of texting and the closeness of audio to access some kind of deep listening. The show is a texting conversation that takes place every night for a few weeks. During the show, this series of meditations on sleep and dreaming and healing from trauma pepper the texting conversation. You’re texting, you're talking about dreaming, and then all of a sudden you get a link to an audio meditation and your conversation partner says they’ll talk to you tomorrow. It was pretty intense, really intimate! The distance from the artist, the fact that I didn't see the artist and only texted them was an interesting tension with the intimacy of the sleep meditations. In the case of What Brings You In, the invitation not to watch and instead to relax offered distance. The therapeutic self reflection was intense but the softness of the gaze soothed me. Sometimes a kind of distance is very freeing as an audience member. Leslie: Yeah—fascinating. Mo: Gosh, this has been really great. I think really specifically, your perspective as an experimental musician on listening as a participatory act is really rich. I'm so interested in your thoughts around gaps and holes as an access offering. Leaving ample room to interpret can be an invitation to participation. Openness is also an invitation to participate.

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed