|

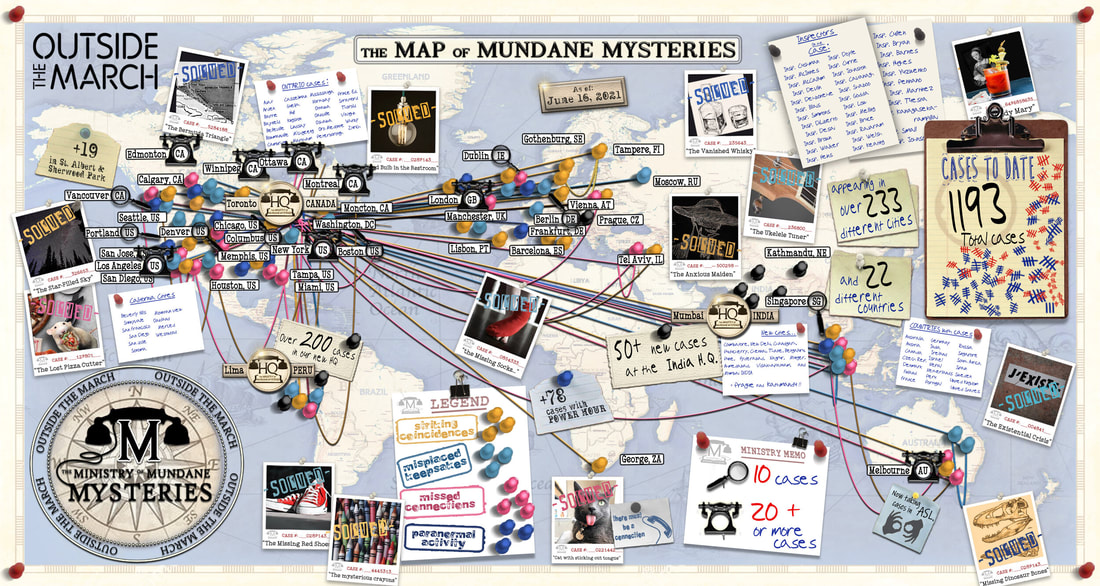

#ThrowBackThursday. This post looks back to a play that we saw and wrote about back in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although this show analysis speaks to a performance I attended in 2020, the Ministry of Mundane Mysteries continues to this day in February 2022! After two successful runs, “solving over 1000 cases in 233 cities worldwide,” the Ministry of Mundane Mysteries now runs their shows on-call, with a team of 25 actors available for booking anytime. You can register for this show here. My mystery was “The Case of the Missing Cake Pan.” Launched in March 2020, The Ministry of Mundane Mysteries is a performance series imagined by Toronto-based company Outside the March to “spark connections through Telephonic Investigation.”[1] In this live, episodic, performance for one, participants are treated to a tailor-made interactive play. Starring the participant, it’s a whodunit that unfolds over the phone. The rundown. Each participant is responsible for thinking up their own mundane mystery. The door that won’t close? Radioactive running shoes? Unripening avocado? No missing socks though, “we’re socked out over here,” as Commissioner Mallory Murtaugh says in the FAQ on the Outside the March website. For six days in a row, at the same time each day, your mundane mystery comes alive through a zany cast of characters that draw you into conversation as you co-construct a personalized adventure. Throughout this adventure, nuggets from the participant are weaved into a structure predetermined by Outside the March. This “fill in the blanks” style of performance, classified by Espen J. Aarseth as using a “configurative” user function, [2] relies on participants to insert responses to a recipe crafted by the artist. Similar to mad libs, the pleasure comes from a low-stakes participatory input into the work. To accommodate the bespoke nature of each mystery, the plays follow a strict dramaturgical pattern that is common to every episode while leaving room for the insertion of unique autobiographical details. Developing an improvisational collaborative dramaturgy, Outside the March explores the balance between structure with flexibility. How big are the spaces I am filling? Will how I fill in my blanks change the direction of the piece? Mundane Mysteries is built as an ordered series of checkpoints and pivotal moments that became identifiable to us as we compared our personal mysteries. Phone Call 1: “The Interview.” The first call is from an Inspector from the Ministry, who is handling your case. Inspector Johnson interviewed me about my mystery, pressing for the names of any suspects or leads I wanted them to follow up on. Did I suspect my roommate? Then, you are asked a list of seemingly random questions. Where do I buy coffee? How long have I lived where I live? Because this first contact is framed as an intake interview, the imposition seems natural. They are leaving no stone unturned! My Inspector is trustworthy, thorough and insists she will do all in her power to solve this case. The phone call ends with the Inspector letting you know they will be in touch. Phone Call 2: “The Informant.” The second phone call comes from a different voice. They call in a whispered panic. “I shouldn’t be talking to you. Don’t tell anyone.” In my case, the caller was an Australian man who used to work for Northside, my favourite local coffee shop. Clearly, he had done his research weaving in details about the Kingston coffee scene, the coffee shop, the Northside menu, and the women who run it. He then divulged that he believes they are behind this missing cake pan. This was my first lead. Phone Call 3: “The Threat.” The third phone call comes from another new voice. At first, the caller purports to be a representative of a reputable business (Loblaws supermarket, in my case). They offer an easy solution to your mystery and invite you to close the case. “You don’t need a cake pan, anyway. You can buy your cakes from us.” As the phone call devolves, you learn they are not who they said they were and instead they work for the folks accused in the last phone call. My caller confessed to actually being a lawyer for Northside and threatened me with a rogue boomerang if I didn’t retract my accusations and call off the investigation . . . or else. Phone Call 4: “The Stakeout.” In the fourth call, your Inspector finally returns, asking you for updates on the investigation or details on any weird phone calls you may have received. When you update them on what the two previous callers have said, they are unsurprised because they are calling you right now from a dangerous undercover situation investigating this very accusation. Whispering and afraid, my Inspector informs me that she is calling me from a hiding spot in the basement of Northside. She has ended up in a “boomerang room” (whatever that is). There is a loud commotion of percussive noise and yelling, and the call is promptly cut short. Phone Call 5: “The Decoy.” The next phone call serves to throw your nose off the trail. This caller offers a weird, out-of-left-field solution to your case and encourages you to close the investigation with the Ministry. In my case, this fifth caller was an optometrist (?!) asking if I had heard the recent rumour circulating about people who wear clear framed glasses (which I do, as I had previously told Inspector Johnston.) Apparently, folks all over the world in clear framed glasses have found themselves unable to see anything square. With hesitation, I said, “Yes let’s” [3] and the phone call ended with the caller shouting, “She bought it!” Phone Call 6: “Case Closed.” Finally, on the last day, you’ll hear back from your inspector, apologetic and embarrassed about the failed stakeout mission. They solve your case, thank you for your time, and play your favourite song to close the call. In my case, the folks had done some research about my roommate’s Mundane Mystery and blamed the case on her Inspector, Inspector Doyle. Apparently Inspector Doyle loves solving mysteries for us so much that he broke into our house, stole the cake pan in hopes that he would get to solve the case and look like a hero. Although he’s since been fired from the Ministry, they still can’t locate the cake pan. In a New York Times review of the Ministry of Mundane Mysteries, Alexis Soloski gave the show a rave review, insisting that the show “let me be who I am (a harried writer and home-schooling flop who might be drinking too much right now) and met me where I was, usually at my kitchen counter, slicing apples for the children’s lunch.” [4] Because this dramaturgical structure feeds into the drama and the well-recognized narrative of a “whodunit,” Outside the March inspired participants to assume agency through small pieces of autobiographical information and spun it into a wild adventure that made the listener feel “seen.” Soloski’s review captures that sense of personal care in an anxious time, The Ministry of Mundane Mysteries “asked about my world, listened and then let me slip free of it, at 10-minute intervals.” [5] Notes

[1] “The Ministry of Mundane Mysteries,” www.mundanemysteries.com. [2] Espen J. Aarseth, Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins UP, 1997), 64. [3] “Yes, let’s!” is a common technique used in improvisation drama games. One person proposes an activity: “Let’s squawk like chickens.” And the expected group reply is “Yes, let’s!” Followed by everyone commencing to squawk. The ethos of “Yes, let’s” is core to collaborative improv where any truth established by one person becomes so for all others. It is a willingness to accept any direction and to endorse it as the new reality. [4] Alexis Soloski, “There’s No Place Like Home (Theater),” New York Times. 16 April 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/16/theater/immersive-home-virus.html [5] Soloski, “There’s No Place Like Home (Theater).”

0 Comments

We are overjoyed to announce the inaugural play/PLAY: Participatory Performance Summit! Taking place from 7-9 April 2022, this summit is an invited gathering of artist-creators and scholar-researchers of participatory performance in Canada. As the first “event” imagined by the team behind play/PLAY, the summit will be hosted by Jenn Stephenson and Mariah Horner with support from production manager Dylan Chenier and stage manager Christina Naumovski. Our goal is to offer summit participants a space to meet and talk with other artists and researchers, present work, and participate in engaging debates on participatory performance. The intention of the summit is to bring together a select group of artists and scholars who share an interest in participatory theatre events in an interactive gathering. By participating in the virtual summit over Discord, participants will have the opportunity to:

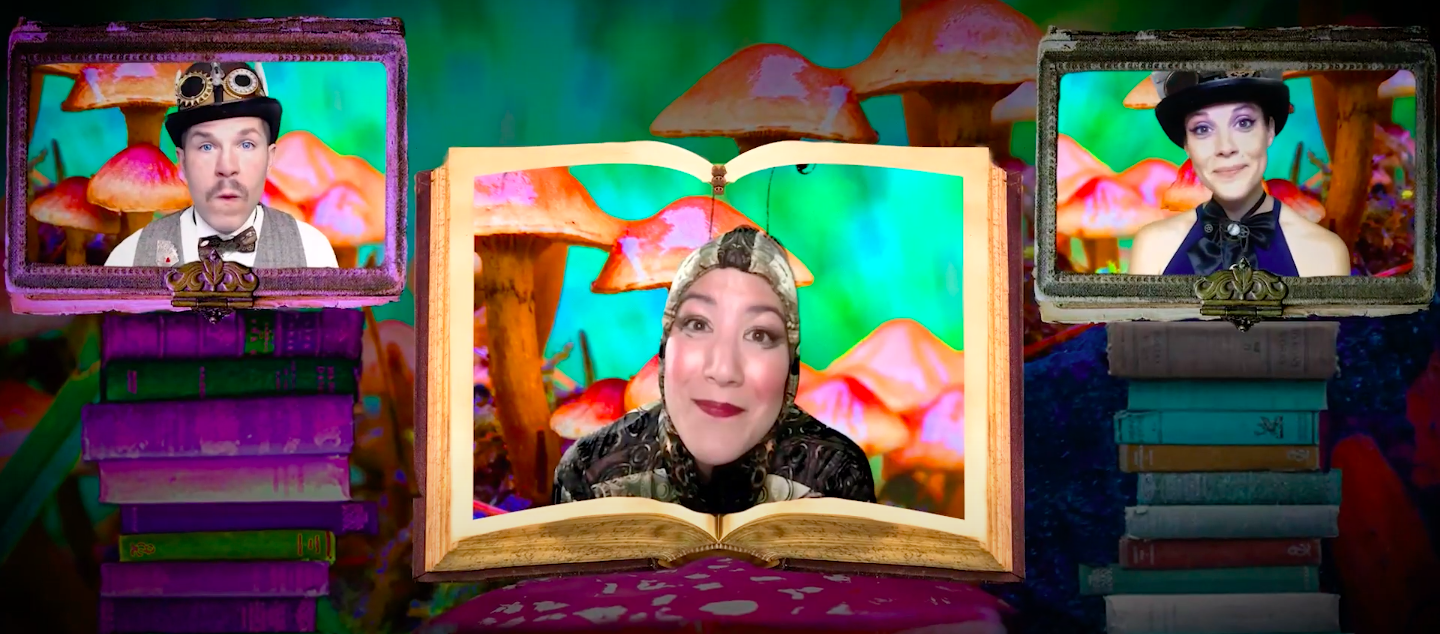

Why are we doing this? First, we’re eager to get the artists from our gallery and the writers from our reading lists in conversation with each other. Over the last four years, while we were collecting and analyzing over 70 participatory shows in Canada in an online gallery, we were simultaneously researching and writing a scholarly book on participatory dramaturgies. As we continue to populate our gallery, we realize we’re watching a community of real experts in the field creating and thinking in real time. We know you, you know each other. Plus, everyone has been so open with us! Strangers are answering our cold calls, artists are sharing archivals, and scholars are sharing nascent ideas in interviews. We have felt a great sense of camaraderie and generosity from the artists and scholars in this cohort and it’s time to bring everyone that we have learned from and with together. As we continue the project of writing this book on participatory dramaturgies, we are excited to put our own principles into practice and participate in conversation on these topics together. Besides the fact that we believe this group simply needs to connect with each other, we are eager to experiment with conference structures during the summit. During a conference panel about participation and immersion in 2020, artist and friend of the Summit Alex McLean wished that all panel talks started after the introductions and biographies. He put his finger on a desire of both artists and scholars to spend more time looking deeply at our participation practices together, moving beyond surface descriptions of our own work, and instead getting into connections and extensions. We are eager to open a space for these artists and scholars to grapple with shared issues and interests. After two years of the COVID-19 pandemic and resultant social isolation, we have felt a real need to play and disrupt in a collective. Because we both work at the intersection between artist and scholar, we know about the value that comes from deep analysis and a dynamic creative commons. At this time, participation in the Summit is fully subscribed, but if you would like to learn more, please email us at [email protected]. Check out some of our confirmed participants here and read more about the summit here. A very common point of focus in participatory theatre performances is on the singularity of the audience participant. I’ve written elsewhere that a recurring marker of certain types of participatory theatre is that it is not only created by me (through my participation) but also for me and about me. [1] The pull to autobiography is strong. And you can see why. If the audience-participant is asked to do something or give something, all they have immediately at hand is themselves—their physical labour, their ideas, their opinions, their ability to solve puzzles, their personal history, etc. In a show like Lost Together, autobiographical play is crafted by and for a solo audience member. In 4inXchange, we share autobiographical details in a small group of four. Even in larger audience groups, like TBD or Foreign Radical or Intimate Karaoke, although we might be surrounded by others, the focus of my experience still solidly lies on me as an individual. My placement in relation to the participation of the others is sometimes serial and sometimes parallel but in every case we are separate. This, however, is not the case in two recent participatory performances I witnessed. Instead of the personal focus of participation as autobiography, in these shows we are amalgamated, we blend together, we are interchangeable, we are a collective. Our individuality is purposely effaced. My self as self is irrelevant. The first of these shows is Saving Wonderland. Presented online as part of the Next Stage Festival, Saving Wonderland blends dramatic storytelling with choose-your-own-adventure decision making and escape room puzzle-solving. The show uses a range of tech platforms including live-action Zoom broadcast, audience chat, and a game app for our phones. The premise of Saving Wonderland is that when Alice visited Wonderland previously she broke it somehow—time is looping and the storyworld is disintegrating— and only Alice can fix it. What is central however is that all of us in the Zoom audience are collectively Alice. There is only one Alice and it is us. The characters address us as Alice. When presented with a puzzle to solve or a choice to be made, we use the game app which works like a poll. The majority vote determines our choices. Similarly, for the puzzles or other digital tasks, if most of the group gets the right answer, we are successful. It is entirely possible to do the show as a disparate assemblage of pure majority rule. On the other hand, on the night that I participated, a leader emerged in the chat and directed our voluntarily coordinated responses, saying “Let’s pick the Red Queen.” or “I think the answer depends on a Fibonacci sequence.” (I, for one, was happy to follow Jackson’s lead. He always knew the right answers.) Either strategy is fine, but whether we remain aloof or choose to consult, the app operates to funnel our input into the oneness of Alice. [2] (The app game task where we each have to mash the on-screen button as fast as we can but without going “over” speaks especially strongly to our role in an invisible collective.) The other show with a similar collective audience character and mode of participation is David Gagnon Walker’s This is the Story of the Child Ruled By Fear. [3] The play is a poetic fable of the journey of the eponymous character of “the child ruled by fear.” Here, a small number of audience participants, (perhaps six or eight people) sit near the front at cabaret tables each equipped with a reading light and a script marked with highlighted section. When their turn comes, each of these participants joins in to read a character. The creator, Gagnon Walker, serves as the Narrator. Audience readers play different characters but also significantly they all, at different times, give voice to the Child. The rest of the audience is also invited when cued to become a chorus. My favourite speech of the chorus is: “We are real. We are real. We are real.” The effect of this collective reading is perfectly described by the show’s promotional blurb which describes the experience as “a playful leap of faith into the power of a roomful of people discovering a new story by creating it with each other.” And so it is. The suggestion emerges that at some point in real life Gagnon Walker might be the child ruled by fear, but then through our dispersed and collective voicings so are we all. We all have fears and sometimes we can be brave and sometimes we can’t. The play evades a simple answer. Nevertheless, the true outcome is that in the end, we have all partaken in a collective journey to create something that we don’t know how it goes, and we journey together with generosity for the risk of participating. The result is a kind of vulnerable rough beauty. Notes

[1] My article “Autobiography in the Audience: Emergent Dramaturgies of Loss in Lost Together and Foreign Radical” is forthcoming in Theatre Research in Canada 43.1 (2022). [2] Spoiler alert: The ending for my play-game experience (which was different from Mariah’s) returning us all as Alice to a blue-sky morning on the riverbank before we ever meet the White Rabbit and before the start of the events of the book Alice in Wonderland. We are told by the Cheshire Cat that the only way to really save Wonderland is for us not to enter in the first place. (See blog post from on 19 July 2021 being unwelcome.) This is emotionally bittersweet but also astonishing in terms of game play and participation. Essentially we are being told that the way to “win” is not to “play.” (!!) We do not belong in Wonderland. [3] Mariah and I were all set to fly to Calgary to see this show as part of the High Performance Rodeo festival in January when the Omicron variant of COVID caused all live performances to be canceled. The creator very generously shared an archival video with us. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed