|

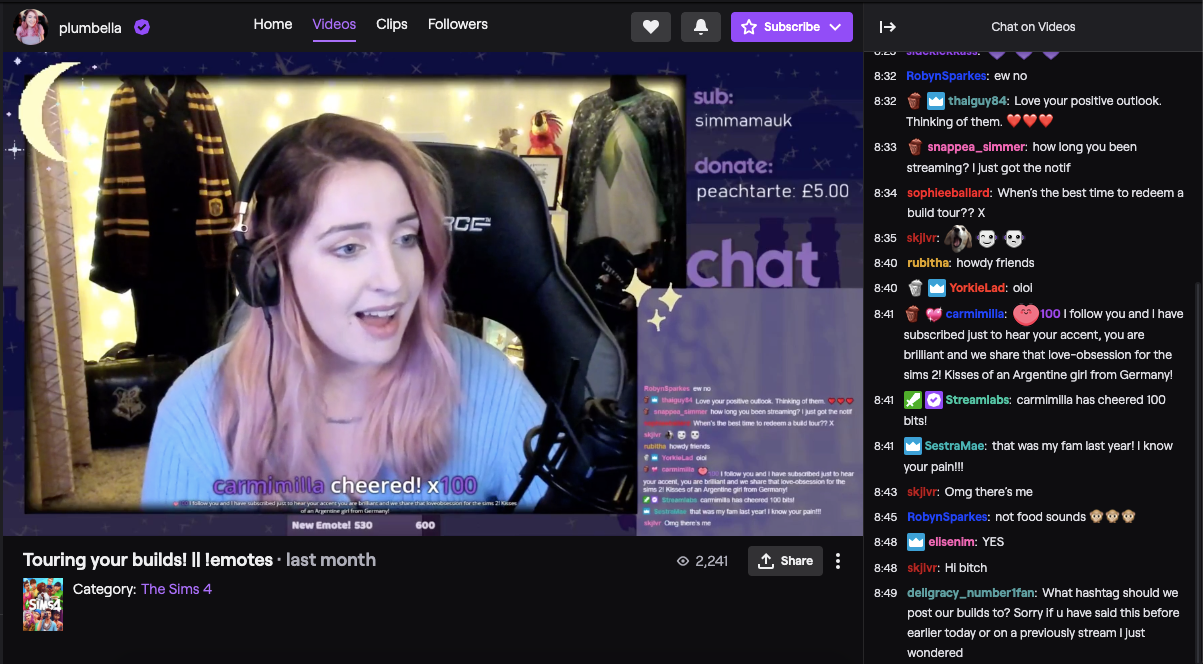

The wonderful whirlwind of the Participatory Dramaturgies Summit was beginning to settle in my mind when an email from Mariah rolled into my inbox, seeking some feedback from participants to inform future iterations of the gathering. I was eager to oblige; the three-day experience was delightfully productive for me. I was still buzzing from the ideas that pinged about our virtual meeting space as theatre creators, thinkers, and communicators pondered the unique affordances of participatory art. I quickly answered the first few questions on the feedback form, but a multiple-choice prompt soon stumped me with a relatively simple inquiry: would you prefer an online gathering or in-person? After a moment of pause in the face of this commitment towards virtual or physical, I selected in-person and moved on. Meeting people from my bedroom was convenient, but of course, the pleasure of connecting in a shared space is tough to forgo when given the option. But then I circled back. When I started to reflect on my engagement in the various panel discussions comprising a relatively large portion of the summit, I was forced to contend with the power of the Zoom chat. I know; part of me hesitates to commit “Zoom” to paper due to my more jaded sensibilities. However, on the other side of skepticism is an opportunity to rethink participation in panel discussions and foster digital community creation. Participants from the summit will likely remember the cheeky chaos of the first panel discussion, which saw the chat erupt after the speakers invited us to award them with points based on their contributions. The idea was to gamify the experience, giving the chat control over who would speak based on the overall value of their point totals. The trick: there was no limit to the number of points that could be given. For 20 minutes, the chat exploded as our little audience rebelled, questioned, and used this system to award unfathomable amounts of positive and negative points to see if our influence would manifest anything tangible. The result of this experiment was the creation of a digital community which immediately reminded me of a Twitch stream. [1] The streamers (panelists) focused on creating content while also addressing the chat community comprised of viewers vying for the attention of both the streamer and fellow viewers. Like many Twitch chats, ours was equally unfollowable at times; the feed quickly scrolled by as new comments rolled in, rivalling Lightning McQueen with their speed. I was confronted with the competing choices of listening to the panelists, reading the chat, or formulating a comment of my own. Scholars have explored the implications of fast-scrolling Twitch chats, including a study from Nematzadeh et al. (2019) which labelled this experience as an overload regime: “If the frequency of messages keeps increasing, participants cannot handle the increased information load indefinitely, and so we expect that, past a certain threshold, an increase in information load will correspond to a decrease in user activity. We call this the overload regime.” [2] Indeed, it should be noted that some viewers were absent from the chat, acting as lurkers in the background whose presence was assumed but not demonstrated. Whether or not this was due to an overload regime would be pure conjecture, but I will say that several participants shared a feeling of exhaustion after the panel ended. None of the other panels would reach that peak level of chat activity over the next few days; this was perhaps for the best, given the challenging cognitive load carried by such an experience. However, I’m grateful that the first one ignited our participatory spirit and cemented an engagement with the chat community. In the end, participating in the Zoom chat was one of the biggest positive takeaways for me. It was satisfying to see others engage with my comments or ideas, and I learned just as much from the group’s responses as I did from the speakers. Resurfacing that Twitch connection, I’ll point to an ethnographic study from Hamilton et al. (2014) completed during the early days of the streaming platform’s rise to prominence, which found that one of the main benefits of participating in the chat was sharing: “Another common reward is the gaining of knowledge and skills available from other community members. In stream communities, this often takes the form of game skill and knowledge, which may be uniquely available from the streamer or their viewers.” [3] I similarly felt that I was taking advantage of the expertise of this found community, and the trading of knowledge made the act of participating in the chat rewarding. Some may worry that the chat could be a distraction, but in my own experience as a panellist, I found the chat to be more of a help than a hindrance. Fielding live questions from audience members with a microphone or from the panel mediator can be stressful because there’s less time to sort through ideas and articulate answers on the fly. In contrast, the digital chat allowed me to read questions from the crowd ahead of time, meaning thoughts could percolate in the back of my head before answering them. The chat also allowed for more direct bridging between the speaker and the crowd by offering opportunities to respond to the concepts and comments raised by viewers. I recall seeing a discussion about Overwatch [4] in the chat pop up during my panel that I happily addressed due to my interest in the game. Sharing my main character of choice and some thoughts on the meta took less than 30 seconds, but in doing so, I was able to contribute to community growth through a personal connection. In another Twitch parallel, the chat also had a dedicated moderator as Jenn and Mariah traded panel and chat mediation duties. In Twitch, moderators can ban viewers if they post offensive comments, but they also serve as facilitators of participation. The same Hamilton et al. (2014) study mentioned previously found that “the role of moderators is not only to keep the discussion in line, but to engage viewers and promote participation and sociability. This most often involves greeting viewers, answering questions, and trying to connect personally with newcomers”. [3] As panel chat mods, Mariah/Jenn similarly responded to comments from viewers, asked questions and fostered this secondary discussion as necessary. The use of chat moderation helped legitimize the textual conversations and combat any fear that a comment would be disruptive or unwelcome. Under their guidance, the chat community thrived. And so with all of this in mind, I returned to the question: would you prefer an online gathering or in-person? Don’t get me wrong, physical gatherings are lovely, and I would jump at the chance to flex my small talk skills and fully loaded dad-joke humour. However, in the face of mounting evidence, I moved my cursor and changed my answer. For a participatory theatre summit, I simply couldn’t resist the immediate participatory potential of the digital chat community and the relationships it built between panellists and viewers alike. Notes

[1] Twitch.tv is a streaming platform where creators play games, chat and interact with viewers in real-time. [2] Nematzadeh, A., Ciampaglia, G. L., Ahn, Y.-Y., & Flammini, A. (2019). Information overload in group communication: From conversation to cacophony in the Twitch chat. Royal Society Open Science, 6(10), 191412. [3] Hamilton, W. A., Garretson, O., & Kerne, A. (2014). Streaming on twitch: Fostering participatory communities of play within live mixed media. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1315–1324. [4] Overwatch [Video game]. (2016). Blizzard Entertainment. A team-based shooter with a vibrant online community and constantly shifting meta-game.

0 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed