|

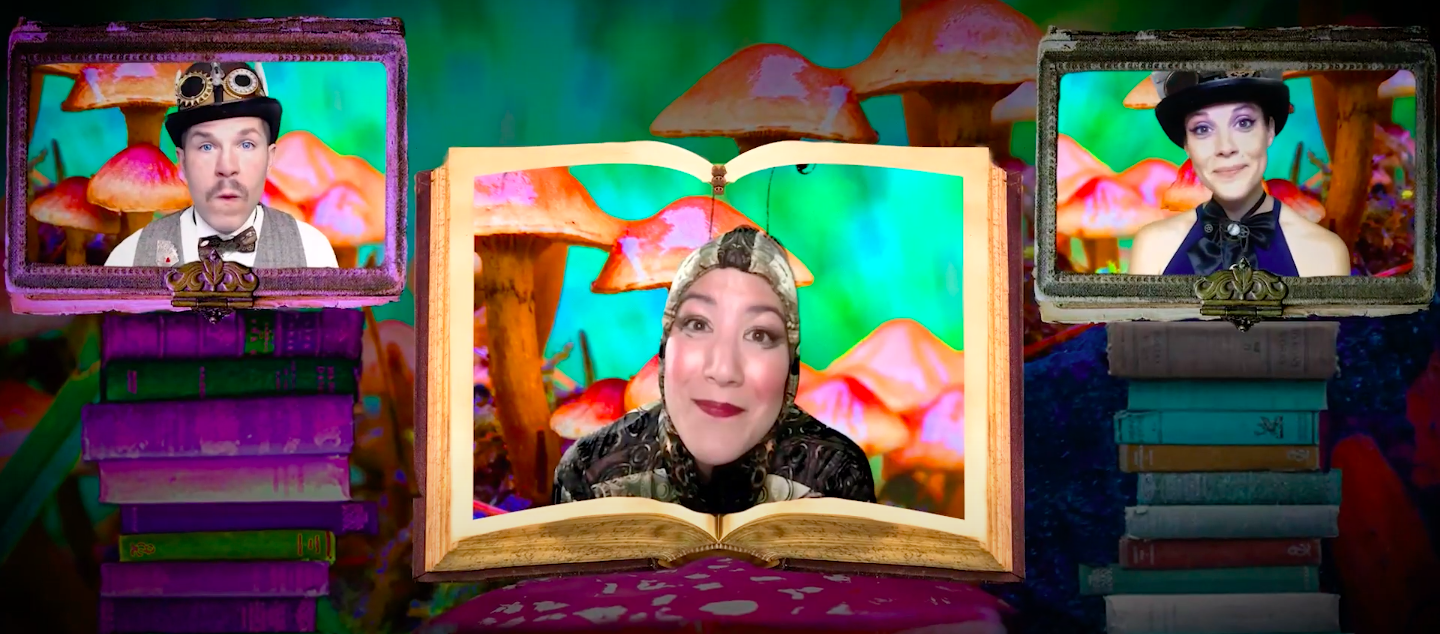

A very common point of focus in participatory theatre performances is on the singularity of the audience participant. I’ve written elsewhere that a recurring marker of certain types of participatory theatre is that it is not only created by me (through my participation) but also for me and about me. [1] The pull to autobiography is strong. And you can see why. If the audience-participant is asked to do something or give something, all they have immediately at hand is themselves—their physical labour, their ideas, their opinions, their ability to solve puzzles, their personal history, etc. In a show like Lost Together, autobiographical play is crafted by and for a solo audience member. In 4inXchange, we share autobiographical details in a small group of four. Even in larger audience groups, like TBD or Foreign Radical or Intimate Karaoke, although we might be surrounded by others, the focus of my experience still solidly lies on me as an individual. My placement in relation to the participation of the others is sometimes serial and sometimes parallel but in every case we are separate. This, however, is not the case in two recent participatory performances I witnessed. Instead of the personal focus of participation as autobiography, in these shows we are amalgamated, we blend together, we are interchangeable, we are a collective. Our individuality is purposely effaced. My self as self is irrelevant. The first of these shows is Saving Wonderland. Presented online as part of the Next Stage Festival, Saving Wonderland blends dramatic storytelling with choose-your-own-adventure decision making and escape room puzzle-solving. The show uses a range of tech platforms including live-action Zoom broadcast, audience chat, and a game app for our phones. The premise of Saving Wonderland is that when Alice visited Wonderland previously she broke it somehow—time is looping and the storyworld is disintegrating— and only Alice can fix it. What is central however is that all of us in the Zoom audience are collectively Alice. There is only one Alice and it is us. The characters address us as Alice. When presented with a puzzle to solve or a choice to be made, we use the game app which works like a poll. The majority vote determines our choices. Similarly, for the puzzles or other digital tasks, if most of the group gets the right answer, we are successful. It is entirely possible to do the show as a disparate assemblage of pure majority rule. On the other hand, on the night that I participated, a leader emerged in the chat and directed our voluntarily coordinated responses, saying “Let’s pick the Red Queen.” or “I think the answer depends on a Fibonacci sequence.” (I, for one, was happy to follow Jackson’s lead. He always knew the right answers.) Either strategy is fine, but whether we remain aloof or choose to consult, the app operates to funnel our input into the oneness of Alice. [2] (The app game task where we each have to mash the on-screen button as fast as we can but without going “over” speaks especially strongly to our role in an invisible collective.) The other show with a similar collective audience character and mode of participation is David Gagnon Walker’s This is the Story of the Child Ruled By Fear. [3] The play is a poetic fable of the journey of the eponymous character of “the child ruled by fear.” Here, a small number of audience participants, (perhaps six or eight people) sit near the front at cabaret tables each equipped with a reading light and a script marked with highlighted section. When their turn comes, each of these participants joins in to read a character. The creator, Gagnon Walker, serves as the Narrator. Audience readers play different characters but also significantly they all, at different times, give voice to the Child. The rest of the audience is also invited when cued to become a chorus. My favourite speech of the chorus is: “We are real. We are real. We are real.” The effect of this collective reading is perfectly described by the show’s promotional blurb which describes the experience as “a playful leap of faith into the power of a roomful of people discovering a new story by creating it with each other.” And so it is. The suggestion emerges that at some point in real life Gagnon Walker might be the child ruled by fear, but then through our dispersed and collective voicings so are we all. We all have fears and sometimes we can be brave and sometimes we can’t. The play evades a simple answer. Nevertheless, the true outcome is that in the end, we have all partaken in a collective journey to create something that we don’t know how it goes, and we journey together with generosity for the risk of participating. The result is a kind of vulnerable rough beauty. Notes

[1] My article “Autobiography in the Audience: Emergent Dramaturgies of Loss in Lost Together and Foreign Radical” is forthcoming in Theatre Research in Canada 43.1 (2022). [2] Spoiler alert: The ending for my play-game experience (which was different from Mariah’s) returning us all as Alice to a blue-sky morning on the riverbank before we ever meet the White Rabbit and before the start of the events of the book Alice in Wonderland. We are told by the Cheshire Cat that the only way to really save Wonderland is for us not to enter in the first place. (See blog post from on 19 July 2021 being unwelcome.) This is emotionally bittersweet but also astonishing in terms of game play and participation. Essentially we are being told that the way to “win” is not to “play.” (!!) We do not belong in Wonderland. [3] Mariah and I were all set to fly to Calgary to see this show as part of the High Performance Rodeo festival in January when the Omicron variant of COVID caused all live performances to be canceled. The creator very generously shared an archival video with us.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed