|

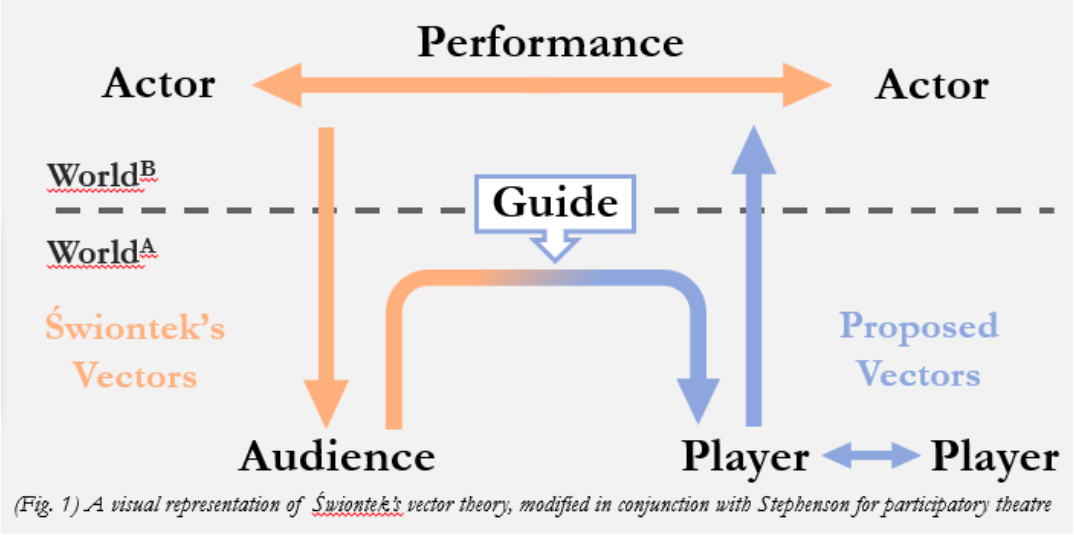

If you were to purchase a video game today, there’s a good chance you would open the case to find a disk and a promotional pamphlet. Notably absent is the rulebook, practically archaic nowadays with the prevalence of gaming culture and the perceived decrease in attention span. Who has time to read a whole book? With enough prior knowledge, the game should be easy enough to figure out as you go. Theatre similarly comes packaged without a rulebook because, of course, we already know how to play the role of the spectator. We know when to applaud, when to be silent, and most importantly, we stay in our seats. Alexander García Düttmann remarks that “it belongs to the rules of the game of art” that one does not interfere with the stage proceedings, and there can be great comfort in accepting the ensuing action is out of our control. However, participatory theatre flips on the house lights and throws the audience a controller. It’s time to become a player. While exciting, this position is often a vulnerable one; as we shed the familiar skin of passivity in favour of agency, we are forced to question the expectations placed on us in this new role. What am I supposed to do? How can I be a “good” participant in this event? What if I do something wrong and ruin the game? The risk of embarrassment or failure often generates apprehension in would-be players. Janet H. Murray raises some parallel concerns about risk inside fictions in her book on immersive game-play, Hamlet on the Holodeck, exploring how we can “regulate the anxiety intrinsic to the form.” As she notes, “suspense, fear of abandonment, fear of lurking attackers, and fear of loss of self in the undifferentiated mass are part of the emotional landscape of the shimmering web” (135). However, we are not doomed to remain lost at sea as we navigate the murky waters of participation. Emerging to answer the outcry for help is a new theatrical role which accompanies us on our journey, gently pushes us onto a safe pathway and critically, teaches us the new rules. Enter, the guide. Much like how Navi accompanies Link in the iconic game The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, the performative guide exists to ensure the success of the player. As an adaptive role that shifts in appearance and design with each show, the guide can appear in a variety of forms. This is unsurprising given the evolving nature of participatory theatre’s structure and content; however, I posit that in successful participatory performances the guide consistently surfaces to combat the player’s risk of failure. In Monday Nights, the guide appears in the form of a coach who encourages audience members to become active figures in a basketball game. The potential for embarrassment here is strong, especially with spectators who feel unathletic or uncoordinated. In this instance, the guide builds a supportive team environment that celebrates participation and minimizes risk through unconditional cheering. By eliminating insecurity, audiences can grapple with the purpose of their participation and appreciate both the value of teamwork and the bonding nature of the game. Tape Escape, though entirely different from Monday Nights in its construction as a participatory experience, also utilizes the guide to great effect. In this video store escape room-performance hybrid, groups of players are accompanied by a store employee. As a natural guide, the employee utilizes an intimate knowledge of the space and an approachable nature to assist when necessary. With puzzle solving at the forefront of the experience, frustration and the risk of offering incorrect solutions can plague players. This poses a significant problem because the story is revealed through each solution, and as such, the performance exists in the interactions between the players and the space. Therefore, an inability to navigate the surroundings directly relates to a lack of progression in the show. Here, the guide steps in to mitigate the difficulty level by providing hints and store insight when players are struggling. Much like a real store employee would assist customers in finding DVDs and offering recommendations, the guide facilitates a meaningful experience for the players. Though the focus remains on the player’s wit and relationship to the unfolding story, the guide alleviates the appropriate amount of pressure to provide a rewarding challenge. Although the form of the guide may change, the role is unified by the widening of theatrical directions of communication. Thinking about communication and metatheatre, Sławomir Świontek first proposed that we understand theatre through “vectors” of performance that carry information. These “meta-enunciative vectors” run perpendicular to each other; one is actor-to-actor (or character-to-character) inside the fictional world, the other crosses the so-called fourth wall, sending information to the audience. Fig. 1 demonstrates how participation modifies these “vectors” by allowing players to send information back, establishing a communication loop between actors and participants. The guide hovers on the line between the actual world of the audience and the fictional world of the performance, which Jenn Stephenson identifies as “worldA and worldB,” respectively. In Monday Nights, we recognize the guide is a coach both within the play and the world of the audience. We already expect guidance from this figure, and so the facilitation of participation is natural. The same can be said for the store employees in Tape Escape, who offer players excellent customer service. In both cases, the guide exists and behaves exactly as one might expect in our world, while also playing a role in the evolution of the performance. The guide approaches the audience in worldA, and once a familiar relationship has been solidified, the transition into worldB becomes possible. The key here is that the guide is not the central figure, but a role which encourages the audience to become active figures themselves. It is through this transformation, and only through this transformation that participatory performances can create the biggest experiential and dramaturgical impact. I hope that as participatory theatre continues to grow, the guide will prevent paralysis from the risk of participation by facilitating meaningful play that is equal parts entertaining and aesthetically satisfying. We all have the capacity to be players, we just need a little help to play the game. Works Cited Griztner, K., and Alexander Garcia Düttmann. (2011). “On Participation in Art.” Performance Research, vol. 16, no. 4 (2011): 136-140. Murray, Janet H. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. New York: The Free Press, 1997. Stephenson, Jenn. “Meta-enunciative Properties of Dramatic Dialogue: A New View of Metatheatre and the Work of Slawomir Świontek.” Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, vol. 21, no. 1 (2006): 115-128. Świontek, Slawomir. Excerpts from Le Dialogue Dramatique et le Metathéâtre. Translated by Jenn Stephenson, Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, vol. 21, no. 1 (2006): 129-144. White, Gareth. Audience Participation in Theatre: Aesthetics of the Invitation. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. *This research was generated as part of a University Summer Student Research Fellowship (2019) funded by Queen’s University.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed